Through his work, Charles White made it his lifelong project to present African American figures and histories too long ignored. Nevertheless, the Chicago-born artist himself was overlooked by the wider art market for years, despite the fact that he was considered the most famous black artist in the US when he died in 1979. As fellow painter Benny Andrews wrote in the New York Times upon White’s death, even people “who didn’t know his name knew and recognised his work”.

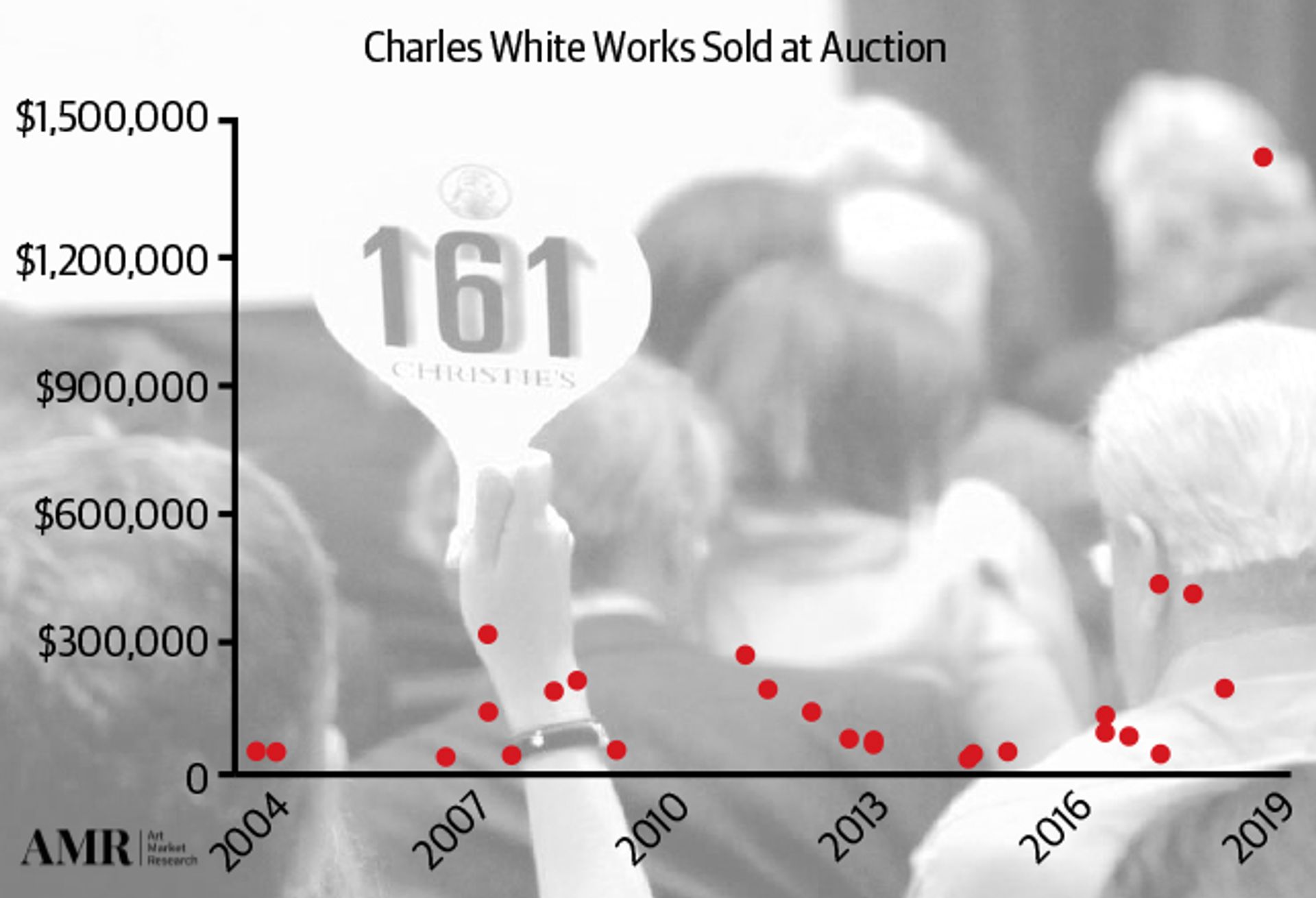

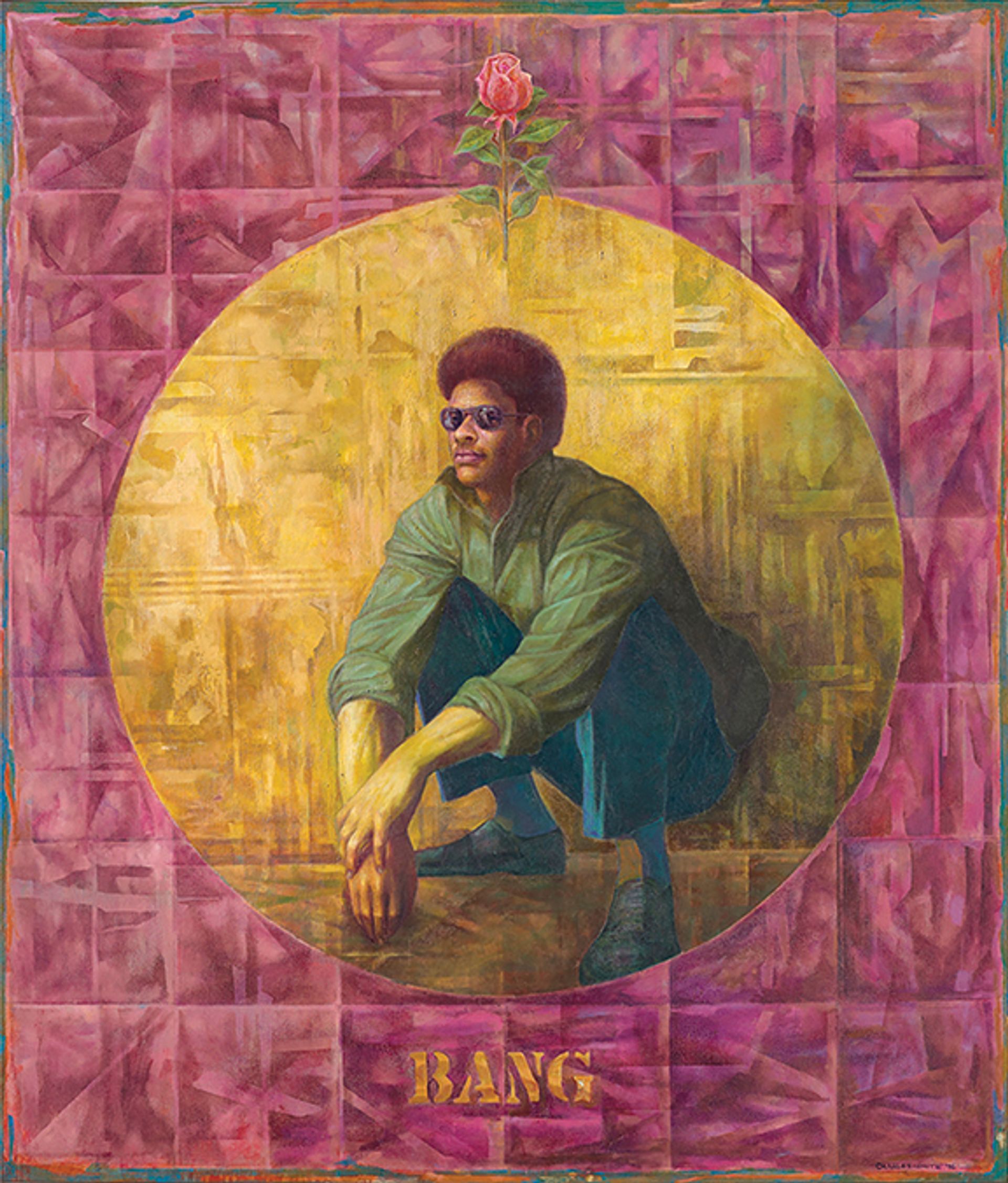

Prices for White’s work may finally be catching up with his prestige. When his painting Banner for Willie J (1976) appeared at Christie’s in New York last November, it was the first time a work by White had even been included in an evening sale. The painting sold for a record $1m ($1.2m with fees) on a single bid. That record was immediately bettered the following night at Sotheby’s, when Ye Shall Inherit the Earth (1953), a large charcoal drawing, sold for $1.45m ($1.8m with fees) after a four-minute bidding war between six buyers.

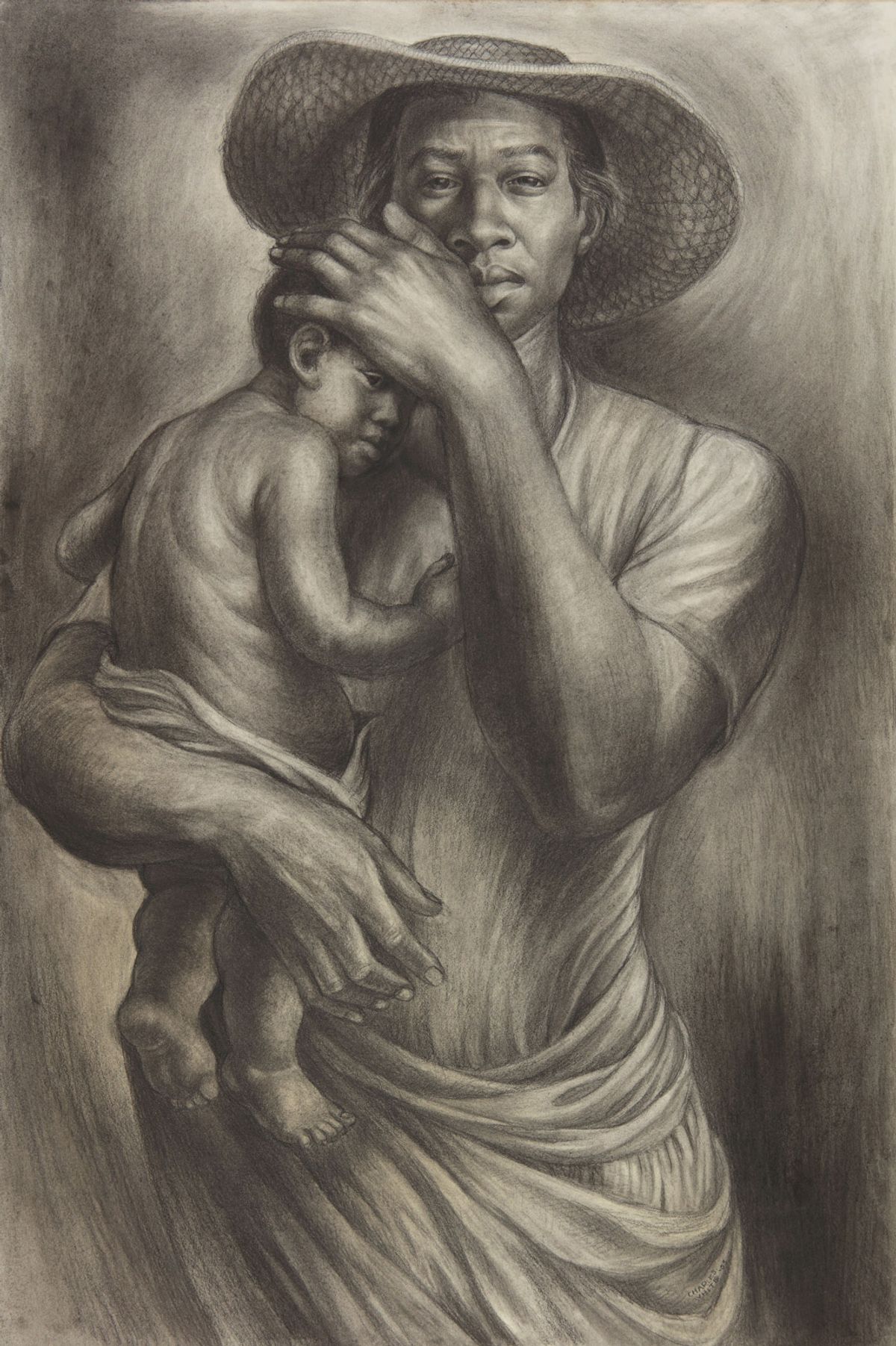

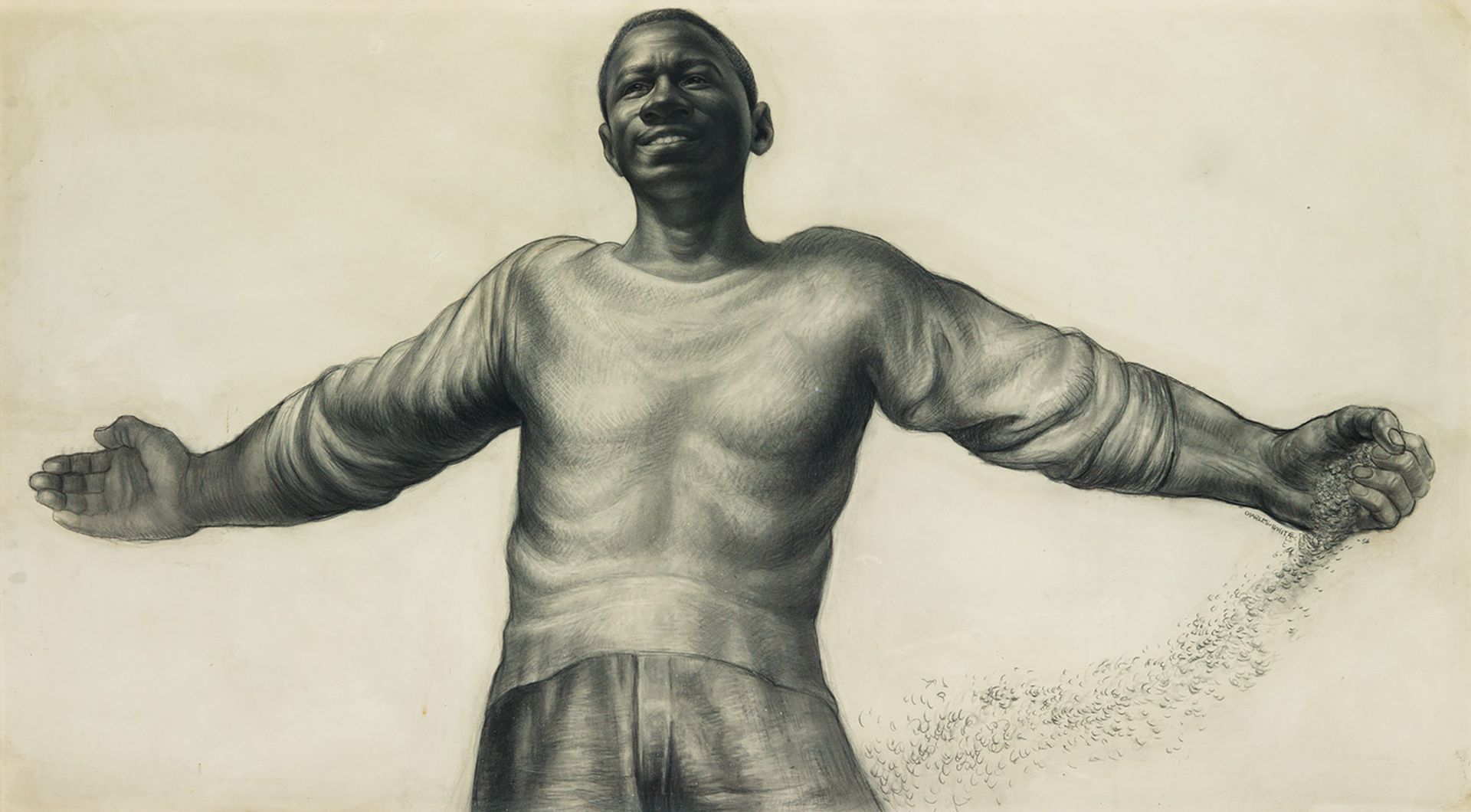

Considered a gifted draughtsman and printmaker, as well as a muralist, White remained steadfastly a figurative artist at a time when Abstract Expressionism, dominated by white artists such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, was lauded as the first specifically “American” form of art. He was prolific during his 40-year career, which began when he was a teenager in his native Chicago after he won a scholarship to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he took drawing classes. The opportunity proved a watershed moment as he had previously been denied art grants and awards due to his race.

By 16, White was showing work with the Art Crafts Guild, a group that contributed to what would become known as the Black Chicago Renaissance, a creative revival that began on the city’s predominantly black South Side and included artists such as Elizabeth Catlett—White’s first wife, with whom he moved to New York—as well as musicians like Louis Armstrong.

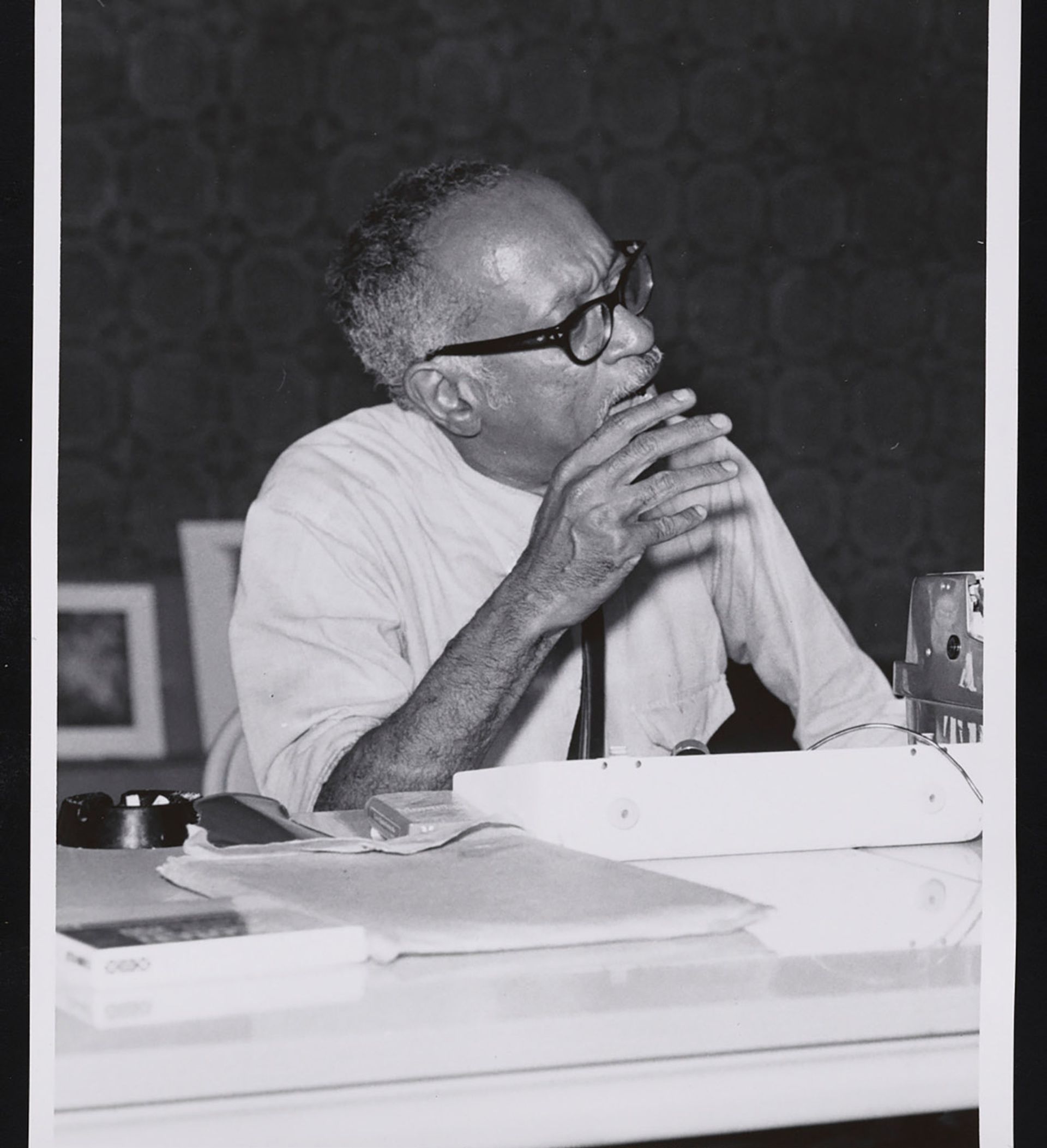

Yet most of his career was spent teaching at the Otis Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design) in Los Angeles, where he became a mentor for a new generation of African American artists who came to study under him, among them David Hammons and Kerry James Marshall, who now holds the record for the most expensive living black artist.

What White passed on to his students is what was central to his own practice—a fierce dedication to depicting the lives of African Americans and an overarching struggle for equality. In 1940, he famously said: “Paint is the only weapon I have with which to fight what I resent.” It is a sentiment that resonates with the political landscape of contemporary America reckoning with its racially fraught history.

Auction prices for White's work have sharply increased in the last 15 years, according to data from Art Market Research. © The Art Newspaper

Prices

Beyond his work’s renewed social relevance, White’s fresh appeal is thanks in no small part to the major travelling exhibition dedicated to him which, before closing last June, toured to three of the most influential museums in the US—the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The dramatic leap in auction prices last autumn is typical of the “retrospective effect”, says David Galperin, the senior vice president of Sotheby’s, referencing the demonstrable trope that an artist’s market value goes up following a major exhibition.

But it is also part of a wider trend, Galperin says: “We are seeing a market recalibration for African American artists and overlooked historical artists from the early 20th century writ large.”

Yet there is still some secondary-market “sticker shock” because of limited public sales records for many 20th-century African American artists who were often excluded from gallery shows and auctions in their lifetimes because of their race.

Alex Rotter, the chairman of Christie’s post-war and contemporary department, explains that with little pricing precedent to go by, and riding the recognition wave of a retrospective, valuing White’s work proved tricky. “It was just a stab in the dark,” Rotter says of the $1m-$1.5m estimate for Banner for Willie J, noting that there is a big discrepancy between primary and secondary market prices.

The New York-based dealer Michael Rosenfeld, who has been selling White’s work for the past three decades, agrees, saying that the recent auction records are “much more in line” with historical private sale prices.

White’s labour-intensive drawings are the most highly sought of his works among collectors, underscored by Sotheby’s record-setting $1.8m sale of Ye Shall Inherit the Earth, a large charcoal drawing. “What’s interesting about White is that what has defined his market is also what has maybe held it back,” says Nigel Freeman, the founder and head of Swann Auction’s African American art department, adding that works on paper generally struggle to command painting prices. “But it is these drawings that major collectors have always coveted.”

Photograph of Charles White at the University of California, Los Angeles workshop "Afro-American History and Culture" Photo: Charles W. White papers, 1933-1987, 1960s-1970s. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Collectors

What has also obscured White’s market is the fact that most of his collectors were friends and family. “Even up to ten to 15 years ago, the major holdings of his work were people who had a connection to him,” Freeman says.

Among those who developed lasting personal and professional relationships with White are the “King of Calypso” Jamaican American pop star and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte, and the Dallas-based entertainment promoter and renowned African American art collector Arthur Primas. Additionally, the Chicago-based Johnson Publishing Company—the magazine magnate behind Ebony and Jet—held a whole group of White’s well-known sepia-toned oil drawings in its corporate collection devoted to mid-century black artists, other works from which were auctioned at Swann in a standalone white-glove sale yesterday that saw 51 auction records set for White's contemporaries like Walter H. Willams and Loïs Mailou Jones.

Only a handful of institutions have particularly rich collections of White’s work, the Art Institute of Chicago being the obvious one given his connection to it, as well as MoMA. Additionally, the University of Texas at Austin received a particularly large group of 23 works donated by Drs Susan and Edmund Gordon—for comparison, the Art Institute has 50.

Galperin says that while private collectors came out in force last November, there is a lot of interest among institutional buyers who are “filling in their collection to address historical and social gaps”, meaning the supply of White’s work on the market may soon be limited.

Indeed, at Art Basel in Miami Beach in December, Rosenfeld showed two drawings by White: I Been Scorned (1954) and a 1976 rendering of the American folk and blues singer Lead Belly for the record that accompanied the eponymously titled biopic of the musician’s life. The dealer says he is currently in negotiations with museums for both.

Charles White’s 1976 oil painting Banner for Willie J. sold for a record $2.6m at Christie's New York last November. That record was re-set for a work on paper by the artist the following night at Sotheby's. Courtesy of Christie's Images Ltd 2019

Turning point

“When you talk about major turning points for an artist’s market, well, for White, it’s now,” Rosenfeld says, noting that the buyer pool is broadening. The dealer has held the largest commercial exhibitions devoted to White, with major shows in 1990 and 2009. But in January 2019, the mega-dealer David Zwirner threw his hat in the ring with an extensive exhibition of White’s large-scale drawings.

Swann previously held the record auction price for the artist’s work since a two-panel drawing of Harriet Tubman sold for $360,000 in 2007. Works by White continued to average around $200,000 to $300,000, and “prices remained pretty constant until 2018, when O Freedom resold for $509,000”, Freeman says—just ahead of the retrospective’s opening that June.

“His work has been in demand by a small audience since I opened the gallery,” Rosenfeld says. “It’s just that many people hadn’t heard of him before. All those Swann sales? I was pretty much always the buyer.” Now he says the influx of buyers is “all over the map – there’s no real demographic”.

Charles White, O Freedom (1956) sold on April 5, 2018 for $509,000.

Pitfalls

White was a strong believer in egalitarianism in general and the democratisation of art specifically. He encouraged reproductions of his work and made many prints himself “so anyone could hang one of his pictures in their home if they wanted to”, Freeman says. Current owners of such works could ostensibly bring these affordable pieces to market for a tidy sum, but therein lies an ideological rift between the artist’s intention and the invisible hand of the market.

Rosenfeld cautions eager buyers against forgeries. With rapidly expanding demand for any previously undervalued artist, “greed and human nature always seep in – it’s tragic”.

Propelling the fakes market for many 20th-century African American artists is the fact that many of them were overlooked or undervalued in their lifetimes, so scholarship and expertise in their work is limited. “You simply can’t go back to the source any more, and there are only a handful of people who worked first-hand with a lot of these artists while they were alive,” he says.

Buyers need to make sure they are working with dealers that have experience with White’s body of work, especially as more works fetch ever higher prices at auction. In Rosenfeld’s view: “The big auction houses don’t have the same depth of knowledge; they only become interested when prices go up.”