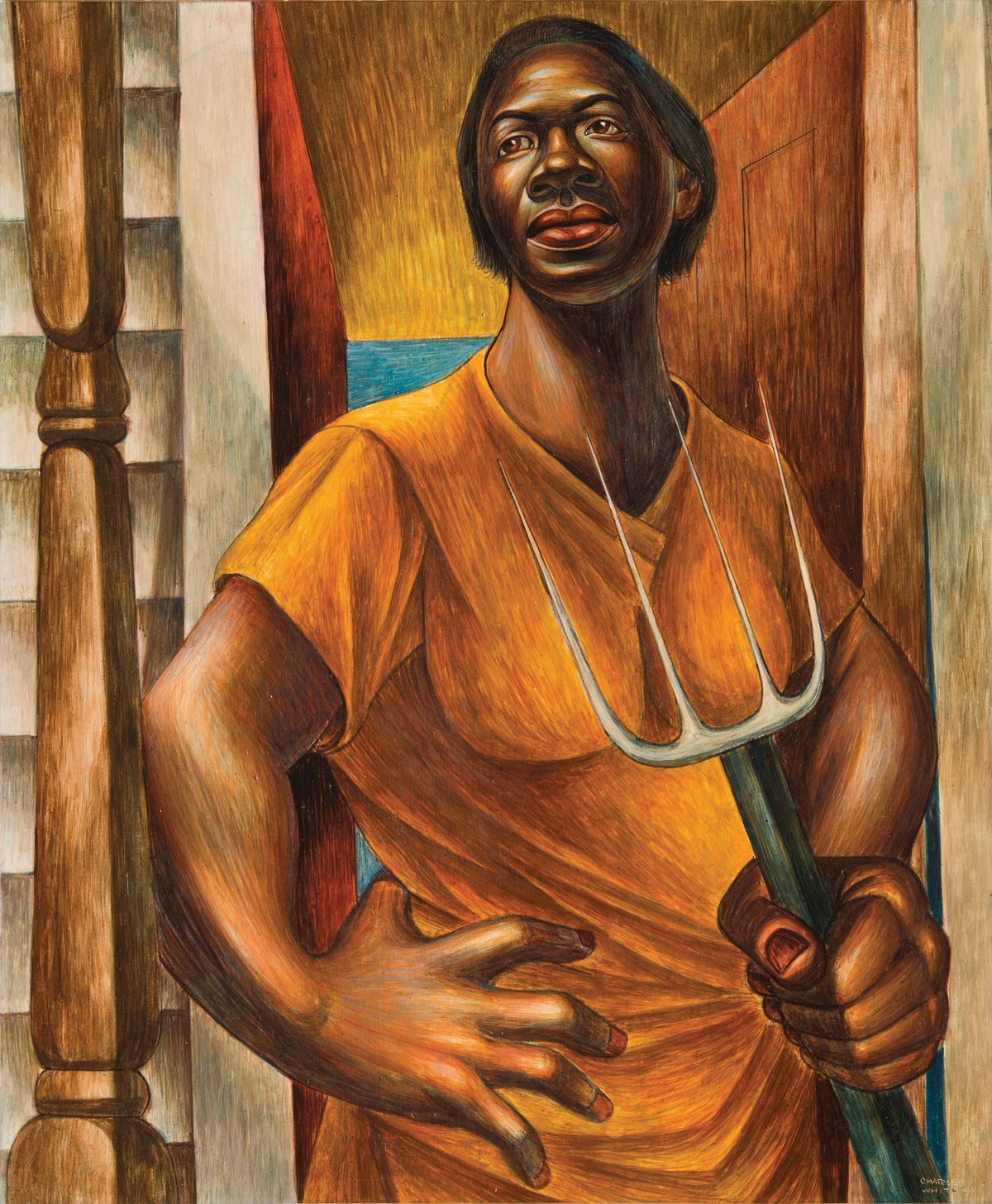

The consummate draftsman Charles White (1918-79) was committed to interpreting the African-American experience in paintings, murals and works on paper for more than 40 years. The left-leaning White was a lifelong activist, and these “images of dignity”, as he described them, were linked to his belief that social inequality should be addressed in art.

The exhibition Charles White: a Retrospective, organised by the Art Institute of Chicago and New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), is part of Art Design Chicago, a year-long initiative supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art. The show opens in Chicago this week before travelling to MoMA in October and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2019.

“One of the great things about the exhibition travelling to the three major cities in which White lived and worked is that each institution has the chance to highlight his life and legacy in its city,” says Esther Adler, the associate curator in the department of drawings and prints at MoMA. Adler worked closely on the show with Sarah Kelly Oehler, the curator of American art at the Art Institute of Chicago.

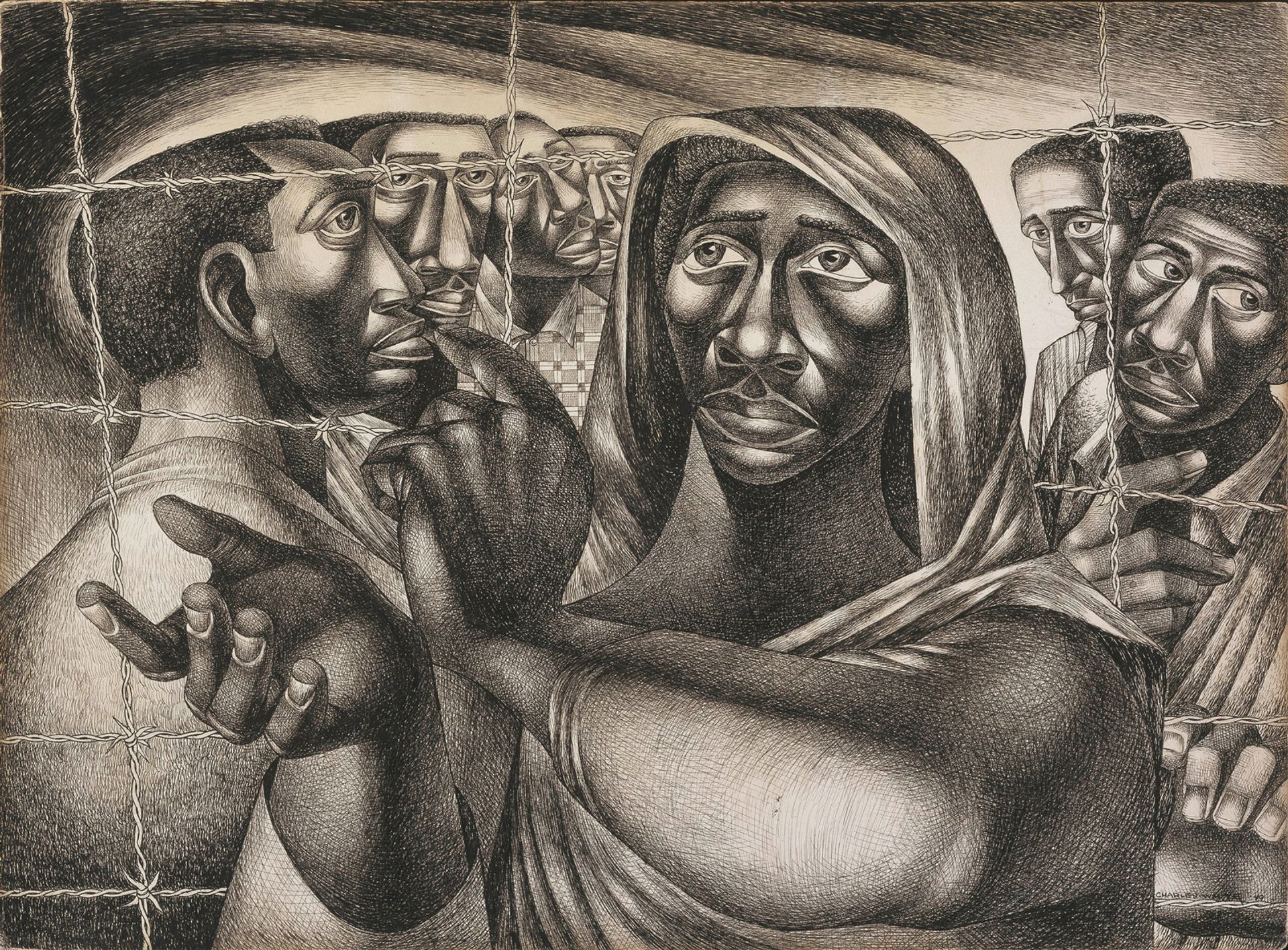

Charles White’s Trenton Six (1949) Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

White grew up on the South Side of Chicago, starting his own sign-painting business as a teenager. In 1937, he was awarded a scholarship to the School of the Art Institute, where he was introduced to the work of the Mexican muralists through his teacher, Edward Millman, who had studied with Diego Rivera.

By 1940, the Chicago Black Renaissance was in full bloom, led by writers including Richard Wright and Gwendolyn Brooks and artists such as White, Archibald John Motley and Eldzier Cortor. The scene revolved around the South Side Community Art Center, which opened that year with support from the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project.

This month’s retrospective—comprising 80 paintings, large-scale drawings and prints, plus 18 photographs—includes the mural Five Great American Negroes (1939-40), painted for a public library in Chicago during White’s employment with the WPA.

Oehler and Adler spent nearly four years working on the project, and the biggest challenge was finding the artist’s works. “Charles White has not been extensively catalogued and many works are coming to market now,” Oehler says. “I spent a lot of time on planes, trying to figure out where they had gone.” ACA Galleries in New York, which gave White his first solo show in 1946, and Heritage Gallery in Los Angeles, which represented the artist after he moved to the West Coast from New York in 1956, were instrumental in helping to find works. Oehler also found pieces in Germany and Russia.

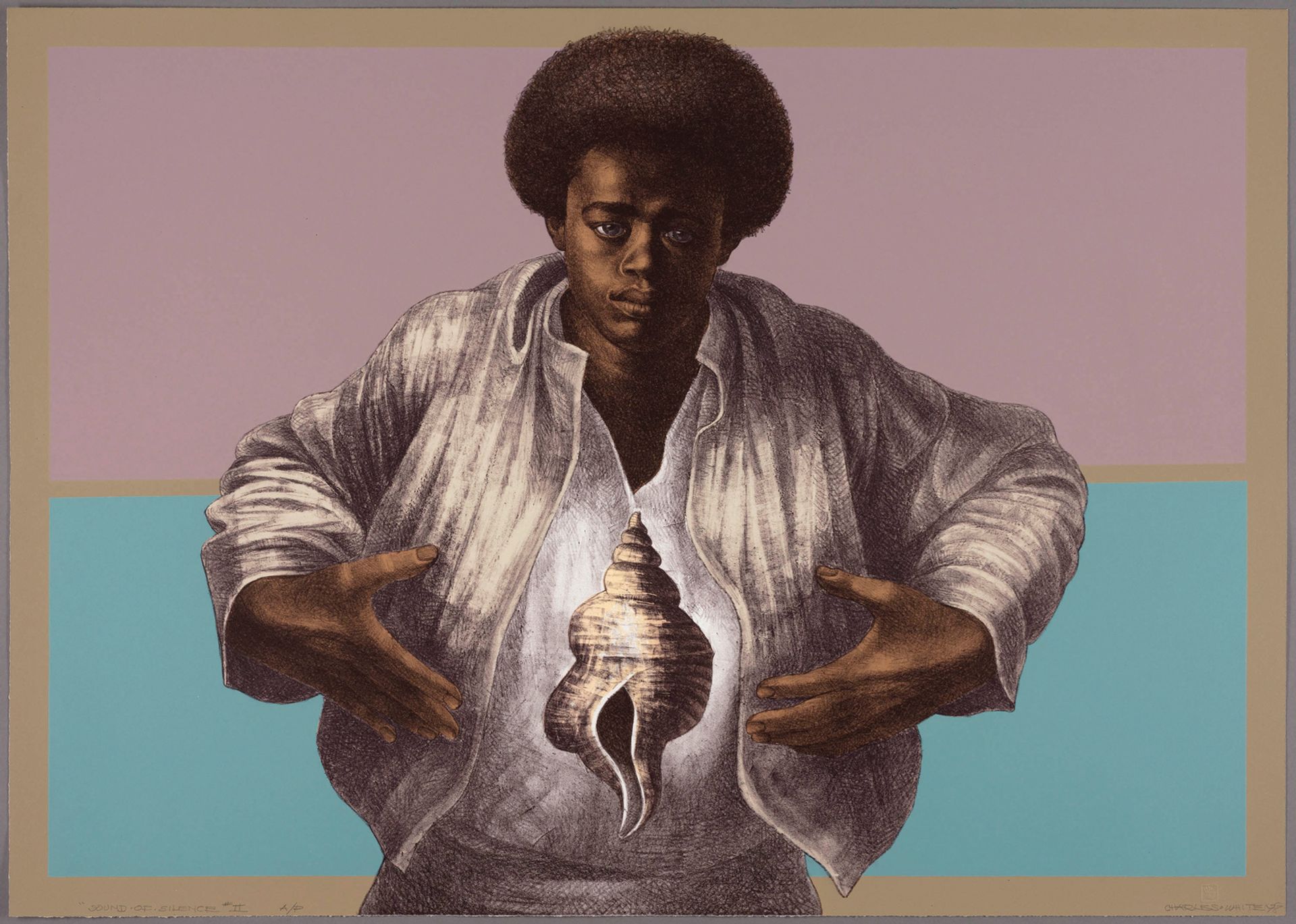

Charles White’s Sound of Silence (1978) printed by David Panosh and published by Hand Graphics, Ltd. The Charles White Archives Inc. The Art Institute of Chicago, Margaret Fisher Fund

In Los Angeles, White taught at Otis College of Art and Design; his students included Kerry James Marshall, who considered White his mentor. In his essay for the exhibition catalogue, A Black Artist Named White, Marshall describes the scene at the time, when figurative and representational art had fallen out of fashion: “A catch-all department called intermedia, in which conceptual, video, performance, installation and land art were routine, was advancing the newest wave of art theory. Those insurgents had just about completed their dismantling of traditional, humanist craft workers. The final stroke was the takedown of a Medieval bronze statue in the campus quad of the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, dragged down by a rope tied to the bumper of a truck driven by the chairman of that department. When the dust settled, everything I was drawn to Otis and Charles White to learn seemed to crumble as well.”

Despite the art world’s increased focus on abstraction, White remained active. He continued to teach, returned to printmaking and exhibited his work until his death in 1979, aged 61.

• Charles White: a Retrospective, Art Institute of Chicago, 8 June-3 September; Museum of Modern Art, New York, 7 October-13 January 2019; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 17 February-9 June 2019