The recent boom in museum shows devoted to African-American artists and the increasing amount of attention paid to these artists in the market has led to a significant rise in forgeries, a prominent dealer is warning. In the past few weeks alone, the New York-based gallerist Michael Rosenfeld, who has long championed the work of many African-American Modernists, has seen fakes purporting to be the work of Alma Thomas, Beauford Delaney, Charles White, Romare Bearden and Bob Thompson.

“It’s a whole generation: you could go from A to Z through the list, from Charles Alston to Charles White. I am seeing fakes attributed to all of them,” Rosenfeld says. Propelling the fakes market is the fact that many of these artists were overlooked or undervalued in their lifetimes, so scholarship and expertise in their work is limited. “You simply can’t go back to the source any more, and there is only a handful of people who worked first-hand with a lot of these artists while they were alive,” he says. Forgers “know they can capitalise on that”.

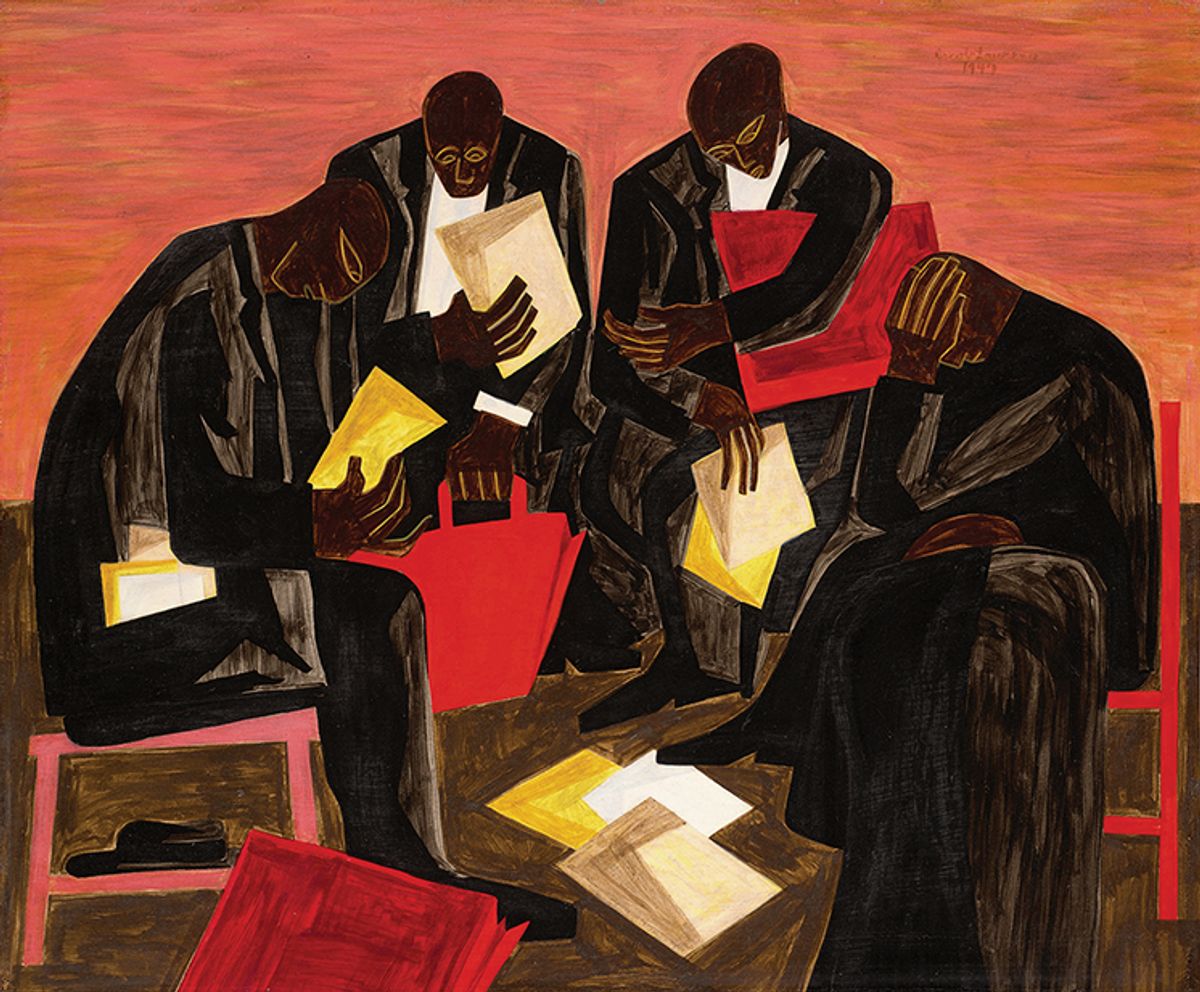

This dearth of information makes it easier for fraudsters to operate and harder for authorities to catch them. Although some of the artists whose works are being forged, such as Bearden and Jacob Lawrence, do have estates and foundations, these organisations are increasingly unwilling to authenticate works due to the threat of litigation.

Alma Thomas’s abstract paintings are among the works to have been forged. © Ellsworth Davis/The Washington Post via Getty Images

“Foundations just aren’t doing this work any more; they can’t afford to,” says Bridget Moore of New York’s DC Moore gallery, which represents African-American artists including David Driskell, Bearden and Lawrence. For this reason, Moore says she has always kept detailed “fake files” on all of her artists.

Cat out of the bag

In 2011, the artist William Toye and his wife, Beryl, based in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, pleaded guilty to charges of fraud after conspiring with a New Orleans-based dealer over the course of nearly 40 years to sell dozens of works painted by Toye and fraudulently signed as Clementine Hunter, an African-American artist who died in 1988. Hunter was self-taught and arguably one of the most significant artists to come out of Louisiana, according to the FBI special agent Randy Deaton, who led the three-year-long investigation.

“It was a remarkable case because she was a folk artist,” Deaton says. “She was well known, but there wasn’t an authoritative archive on her career,” which made it easier for Toye to pass off his own paintings as hers. One of the things that gave away the forgeries was the presence of cat hairs on some canvases, says the conservator and forgery specialist James Martin, who consulted on the case. Currently the director of scientific research at Sotheby’s, Martin is the founder of Orion Analytical, which was acquired by the auction house in 2016.

“Cat hairs, the same discrepancies in under-drawing and signatures, and dirt wiped on to [the works] to impart a false appearance of age linked the fakes I examined to a common source,” he says. Ultimately, though, it was the sheer number of forged works attributed to Hunter by the Toyes that gave Martin a substantial sample size, enabling him to find the forgeries. “Generally speaking, problems with forgeries become easier to spot when seen in large numbers,” he says.

Special Agent Randolph J. “Randy” Deaton IV (Federal Bureau of Investigation) takes a close look at a Toye forgery of artist Clementine Hunter at the Gallery 2 show ©NCPTT/National Park Service

Rosenfeld says he first started to see forgeries of work by artists such as Lawrence, Bearden and Horace Pippin “20 to 30 years ago”, when their works first started to appear on the secondary market. Today, Rosenfeld says he often encounters fakes when collectors and institutions contact his gallery seeking the rights to reproduce an image of an artist’s work, often in exhibition literature. This underscores the fact that “collectors and curators need to be cautious”, Rosenfeld warns, adding that he recently encountered this problem in relation to a picture purportedly by Bob Thompson. The artist’s work is in high-profile shows including Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, an exhibition organised by Tate Modern in London, currently on view at the Brooklyn Museum (until 3 February) and travelling to the Broad in Los Angeles in March.

Concerns about the authenticity of several works by Charles White were raised when the Art Institute of Chicago was organising the artist’s first major survey show, a source at the institution says. The exhibition, seen in Chicago last summer, is currently at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (until 13 January) and is due to travel to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (17 February-9 June). This highlights a potential pitfall for museums that organise such exhibitions: any works that are considered questionable are simply excluded from display, which could lead to a distortion of an artist’s true achievements.

According to the FBI special agent Timothy Carpenter, who manages the agency’s art crimes division, “it’s not the first time this issue has come up”, but he adds that the fake works that are surfacing are likely to be small or not of very high value, which may make dealers disinclined to formally report them.

Rosenfeld, however, believes that the rate at which he is seeing questionable works attributed to African-American artists suggests that the problem is more widespread than many people think. He describes the situation as “increasingly epidemic”, given the large sums for which many works are selling. But there remains one certain way to spot a fake, he says. “If it seems too good to be true, then it probably is.”