What did it mean to be a black artist in the US? Was there a black art or a black aesthetic? These are some of the broad questions posed by the exhibition, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, which opens to the public at Tate Modern tomorrow (12 July-22 October).

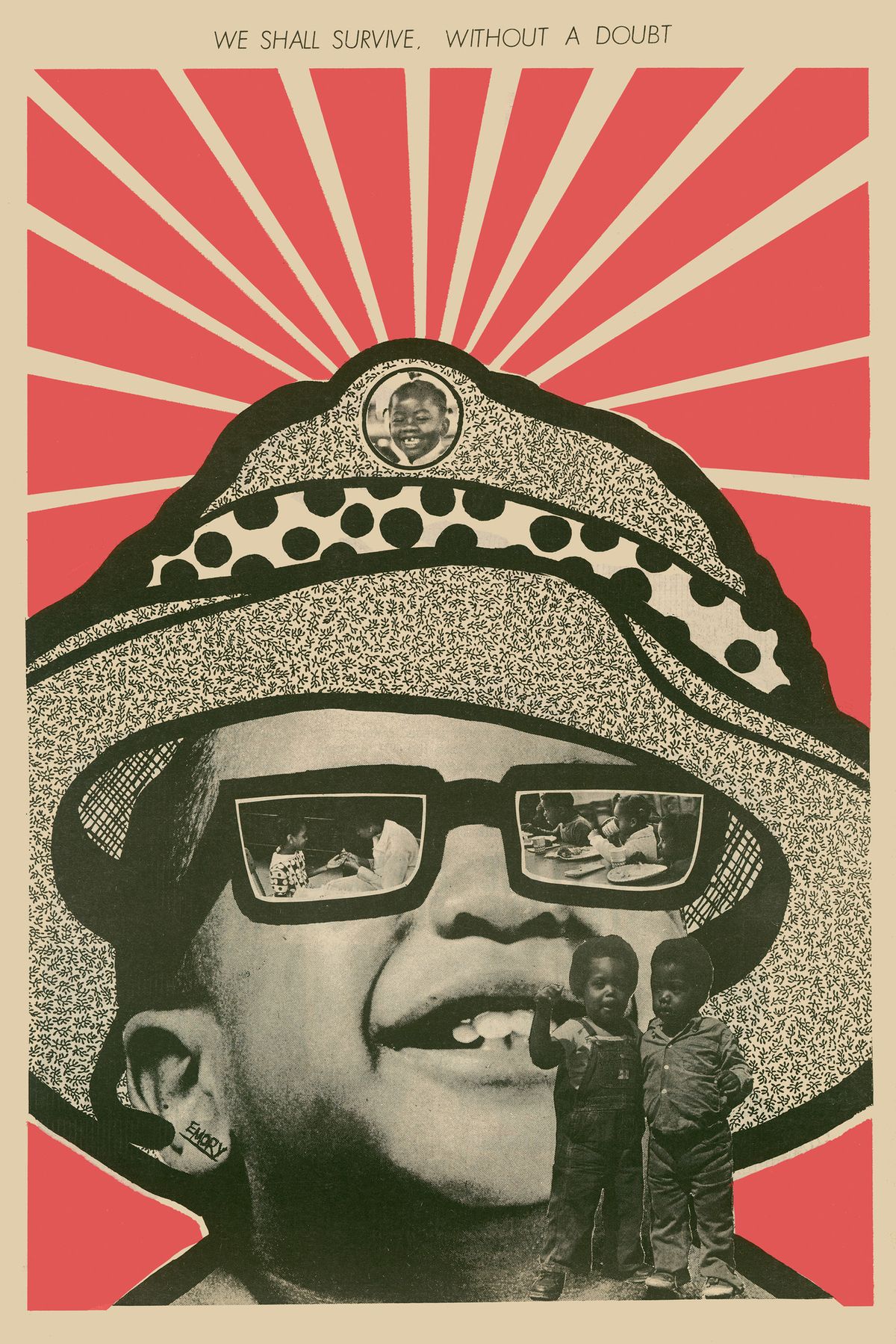

It is an ambitious undertaking by the curators Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley, not least because so much of the art on show defies categorisation. Some is overtly political, created in the streets rather than the studio. Take, for example, Emory Douglas’s designs for the Black Panther manifesto or Darryl Cowheard’s photograph of Amiri Baraka, the leader of the Black Arts Movement, which hung on the Wall of Respect, a mural depicting pivotal black figures and leaders that was first painted in Chicago in 1967.

Other works, meanwhile, are radically abstract in their approach. Frank Bowling’s Texas Louise (1971) is a sumptuous pink and orange sunset that recalls both Turner and Rothko.

The exhibition begins in 1963, at the height of the US civil rights era and at the birth of the Black Power movement. It covers the next two decades, featuring 150 works by more than 60 black artists who in various ways shaped this tumultuous period of political unrest and police brutality.

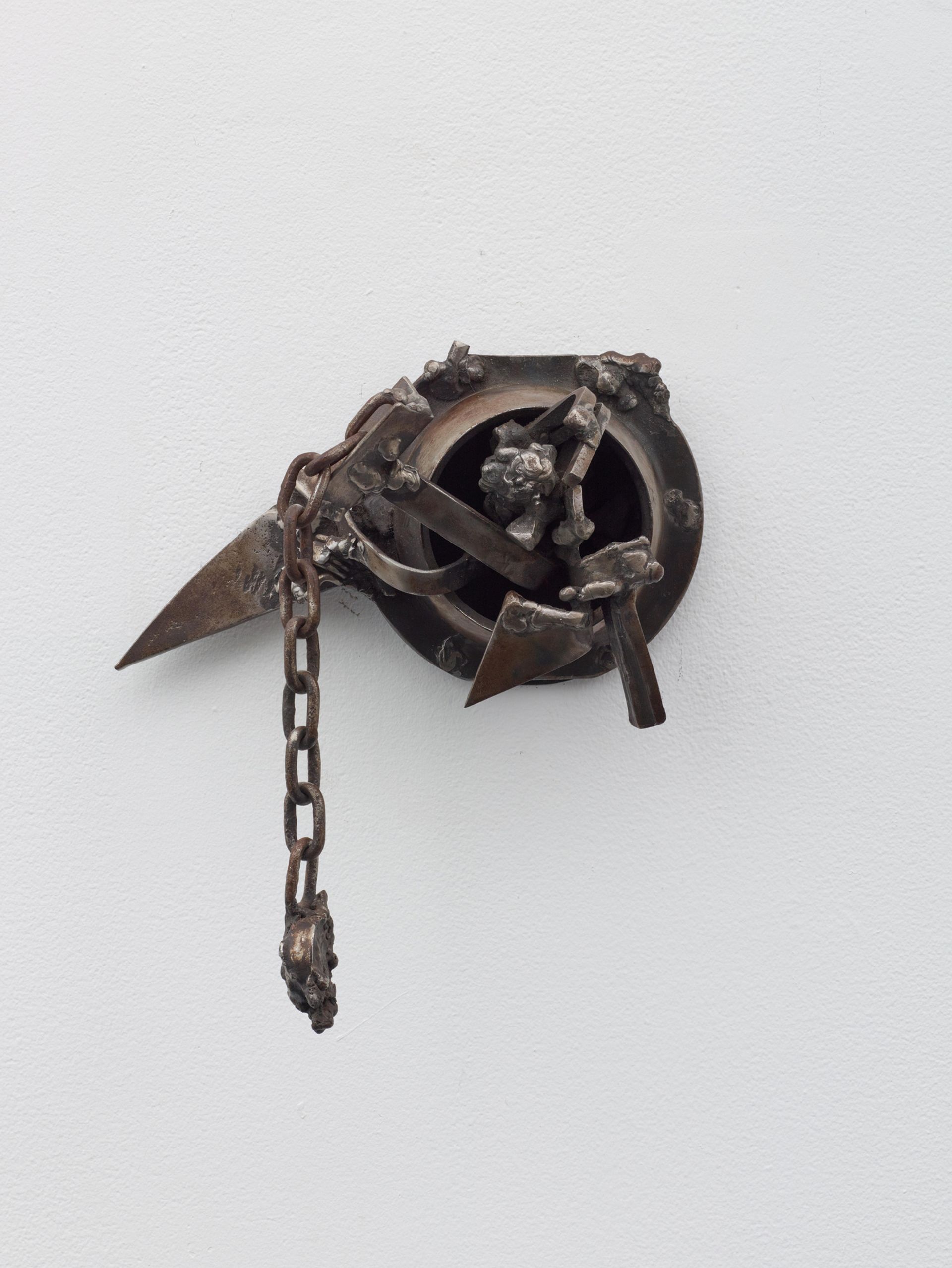

Many of the issues addressed in the show, including the debate around “Black Art”, still resonate today. For the Texas-born artist Melvin Edwards, if there is such a thing as an African-American movement, it is plural. “A movement does not mean a style,” he says. “There are many individual works and none of them sums up everything. Nobody is that profound or wise.”

Edwards is showing three sculptures from his long-running Lynch Fragments series, created from chains, hammers and other recognisable objects. One, titled Some Bright Morning (1963), is named after an African-American community that was threatened with the phrase: “If you people don’t behave, some bright morning we’re going to come and take care of you.”

Although the works might allude to slavery, Edwards points out they are as much about blacksmithing or how poets use the word love. “Most slaves were never chained,” he says. “Do you think an owner of 500 slaves could afford to chain each and every one? Naturally chains are a symbol of oppression, but they are in the mind of the perpetrator, the men who wrote the Constitution.”

Eighty-year-old Edwards, who considers himself “very much self-taught”, was one of the first African-American sculptors to have a solo museum show in the US. The exhibition at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, organised when he was just 27, kick-started his career.

Commercial success came later, however. “I didn't have a gallery show until I was 50,” he says. “They weren't showing anyone else black.” Edwards is now represented by Alexander Gray Associates in New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery in London. The sculptor is creating a new body of work to be shown at Stephen Friedman in October.

Edwards commends the Tate curators for putting on a show that grapples with questions of race, identity and power. “When exhibitions like this come up, they are important but there is so much missed in understanding,” he says. “We need around ten shows like this. That Mark [Godfrey] is putting this together is admirable, no question. But there’s lots more to do.”

Frances Morris, the director of Tate Modern, acknowledges this is just the beginning. “This is a community of American artists we have not recognised in our collection. Today is a turning point for those artists.”