Scientific analysis of paintings on the wall of a remote cave in Patagonia, Argentina, suggest they are the oldest known example of rock art in South America, according to research published this week.

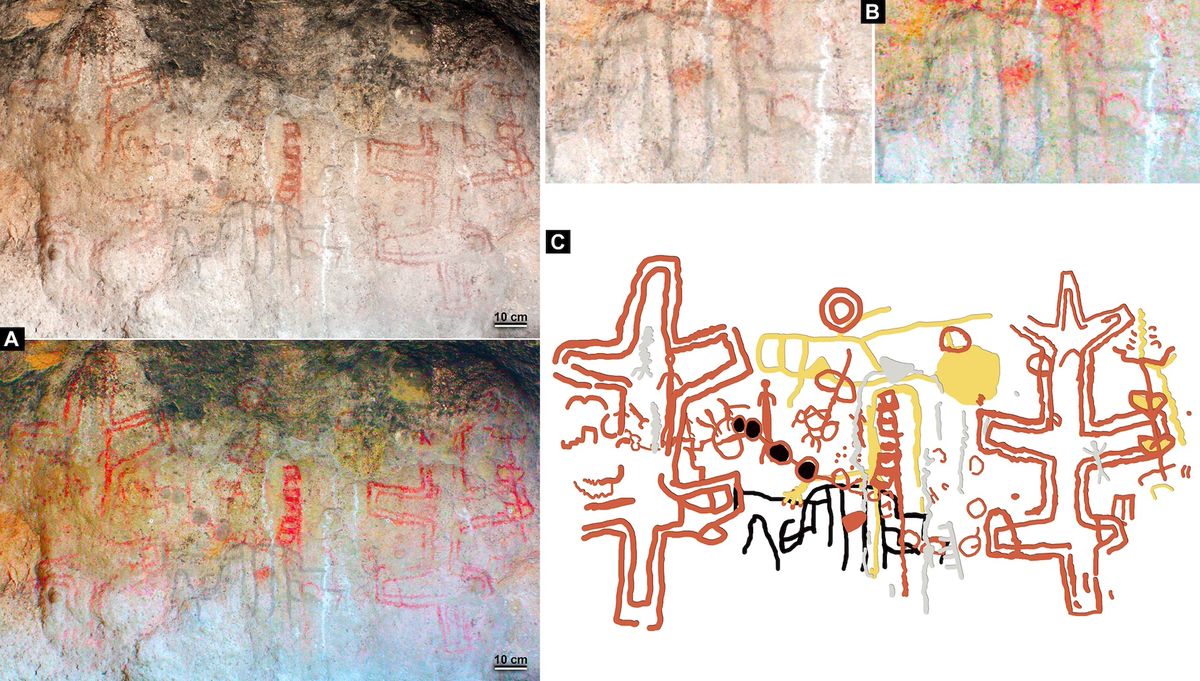

The researchers behind the project, whose findings were published in Science Advances on 14 February, say that the mysterious comb-like pattern adorning the walls of Cueva Huenul 1—which sports nearly 900 other paintings of humans, animal figures, plus abstract designs—first appeared 8,200 years ago. The comb-like markings were initially assumed to be only a few thousand years old; their revised dating suggests an early communication system used across heat-ravaged populations and generations.

“We got the results and we were very surprised,” Guadalupe Romero Villanueva, an author of the study and an archaeologist at Argentina's National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) and the National Institute of Anthropology and Latin American Thought (INAPL) in Buenos Aires, told The New York Times. “It was a shock, and we had to rethink some things.”

“As interesting as the ages are, for us it’s more significant that they span, more or less, 3,000 years of painting basically the same motif during all this time,” said Ramiro Barberena, an author of the study who is an archaeologist at CONICET and at the Temuco Catholic University in Chile. Barberena added that these findings provide evidence “for continuity in the transmission of information in these very small and very mobile societies”.

Patagonia was not inhabited by humans until 12,000 years ago; hostile climactic shifts encouraged these small populations to abandon the caves in which they sheltered a few thousand years after their arrival. This period of hardship and migration overlaps with the results of the paintings’ radiocarbon dating, suggesting that these patterns helped preserve memories and oral traditions. The artists continued to draw these designs on top of existing motifs with charred wood paint for thousands of years.

“You cannot help but think about these people,” Romero Villanueva said. “They were at the same place, admiring the same landscape; the people living here, maybe families, were gathering here for social aspects. It’s really emotional for us.”