The readers of the Daily Mirror never did this. It is June 2016 and 200 protesters are pounding the glass walls of Tate Modern’s swanky new Blavatnik Building. Inside are artists sipping champagne, invited for a special preview; outside the activists are chanting “Where is Ana Mendieta?”

Ana Mendieta was an artist and the wife of Carl Andre, who died in a New York hospice last week. Mendieta met a more violent end—she fell from the window of the 34th floor apartment she shared with Andre. Andre told a 911 call they were fighting over his greater success as an artist, and it was an accident or suicide. He was charged for her murder but was acquitted.

The demonstrators had no such doubts. “Carl Andre killed Ana Mendieta” read their placards. “Oi Tate, we’ve got a vendetta, where the fuck is Ana Mendieta?” Their grudge against Tate? Why could the gallery, which claimed its new extension was to show a more diverse view of art history, not find room in its new displays for one of Mendieta’s visceral feminist works, while proudly showing Andre’s minimalist 1966 sculpture Equivalent VIII?

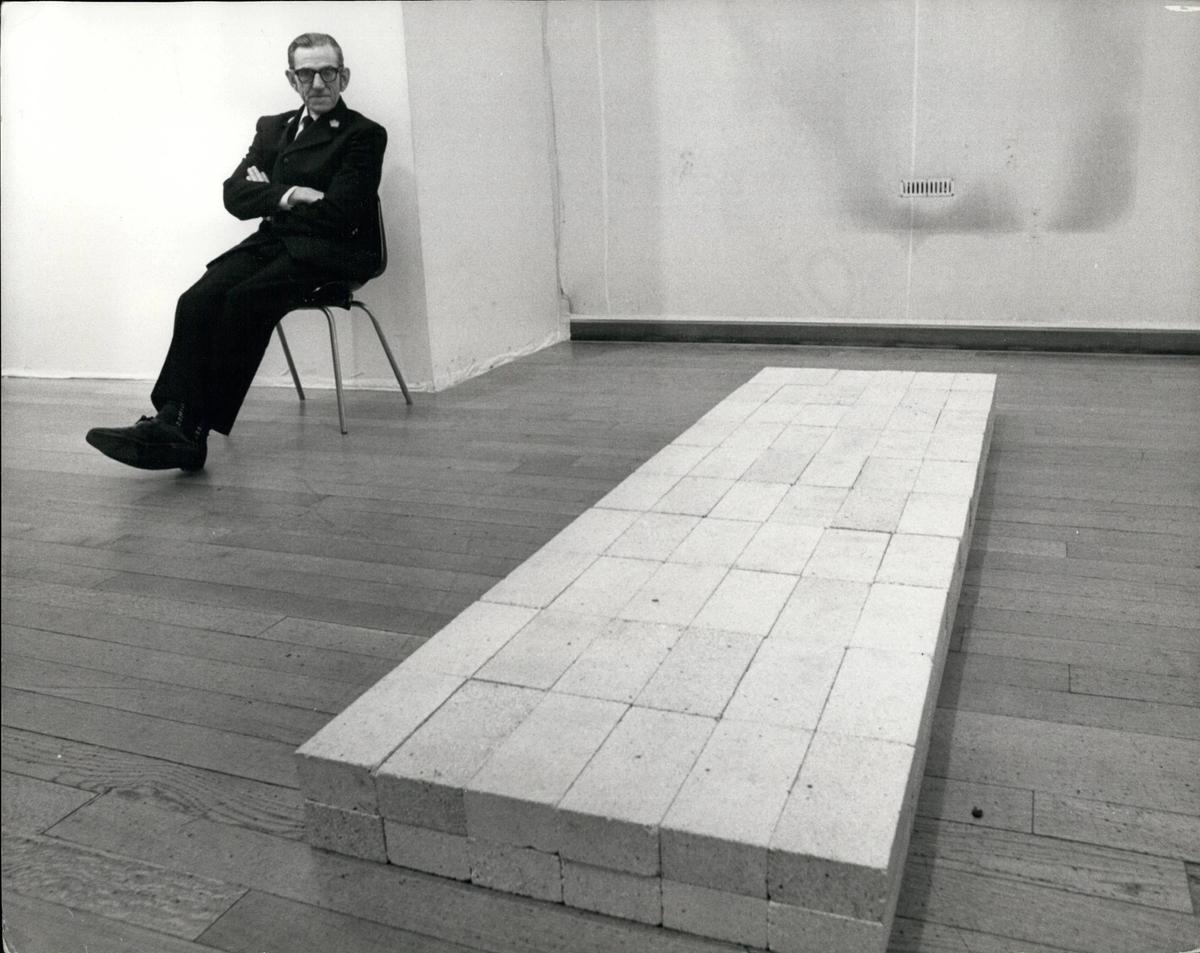

Of course this was not the first time Tate had come under fire because of Equivalent VIII. It is made from 120 yellowy-grey fire bricks, arranged in a rectangle. It accrued little notice when it was purchased for £3,000 in 1972. But a few years later an enterprising journalist, on the hunt for a salacious story about the British national collection of Modern art, spotted it in an acquisitions report and blew it up into a front page story. “What a load of rubbish”, proclaimed the tabloid newspaper the Daily Mirror. 'Why was Tate wasting public money on a pile of bricks?', 'My kid could have done that!', 'My builder could make it for half the price', etc, etc.

“The bricks” became a cause célèbre and the art establishment rolled into action. It wasn’t just a pile of bricks, it was a really clever and important piece of Modern art, actually. Despite the point of the piece—one of a series of different configurations of the same number of bricks, hence “equivalents”—being slightly lost by showing VIII away from its siblings, defending it became a point of honour for a generation of curators, art historians and museum administrators. Culture was under attack from the philistines, and there was only one side to be on.

Forty years later, the whole thing seemed rather silly. Because the Minimalism-loving art curators had won, and won big. Tate Modern—itself looking like a giant version of Andre’s brick cuboid—had became one of the most visited museums in the world. It was packed with the kind of difficult, unpretty Modern art exemplified by Equivalent VIII; the high-minded curation was as a dry as the dust that flakes off its bricks. And yet people came in their millions, while the readership numbers for the Daily Mirror plummeted.

But a new generation of critics was growing up, for whom Andre’s alleged crime weighed more than his artistic achievements. Tate and the rest of the art world could dismiss previous critics as reactionary, ignorant, uncultured, behind the times. The weekly diatribes by the Evening Standard’s art critic Brian Sewell against Tate’s then director Nicolas Serota, could be brushed off as an old man shaking his fist at the clouds. But the new wave are young, female, fearsomely well-informed and passionate about social justice—the likes of White Pube and Alice Procter. They aren’t as easily ignored, not least because many employees of Tate and similar institutions heartily agree with them. (Tate later hired one of the Ana Mendieta protesters, Liv Wynter, into a freelance role, which she then quickly resigned from in a media storm over the institution’s “appalling response to sexual harassment and violence”.)

Even in less than a decade, times have changed. In the wake of #MeToo, it seems remarkable that we once gave Andre the benefit of the doubt. Ana Mendieta’s story—a female artist possibly killed by her husband, her work ignored and undervalued—has become more widely told, not least in the 2022 podcast Death of an Artist. The curator and podcast host Helen Molesworth told The Art Newspaper: “One of the things this period has done is shown us the blinders of our education, the lies of our education […] The story of Carl Andre and Ana Mendieta offers us a case study that lets us really test some old ideas and new ideas, and the cultural sea-change in how we think about domestic violence makes this story very different than the way it was told in the late 1980s.”

But here is a danger. It is much more comfortable for museums, many of which are trying earnestly to diversify their collections, to side with the protestors than with the anti-Modernist critics of yore. It is more rewarding to feel you are on the side of good, defending the underprivileged, than on the side of the nay-saying fuddy-duddies. But both these critiques have their strengths and their weaknesses. Museums must take seriously those who feel alienated by Modern art, as much as those who feel that museums uphold inequality. They must also defend art and artists against attacks from progressive activists just as much as from reactionaries. Ultimately, art museums need to know what they stand for, to be alert to criticism but not knocked off course by it.

Whatever you think happened that night in Andre’s apartment, it is a testament to his work that his humble pile of bricks continues to be a thorn in the side of the art world over half a century after it was laid.