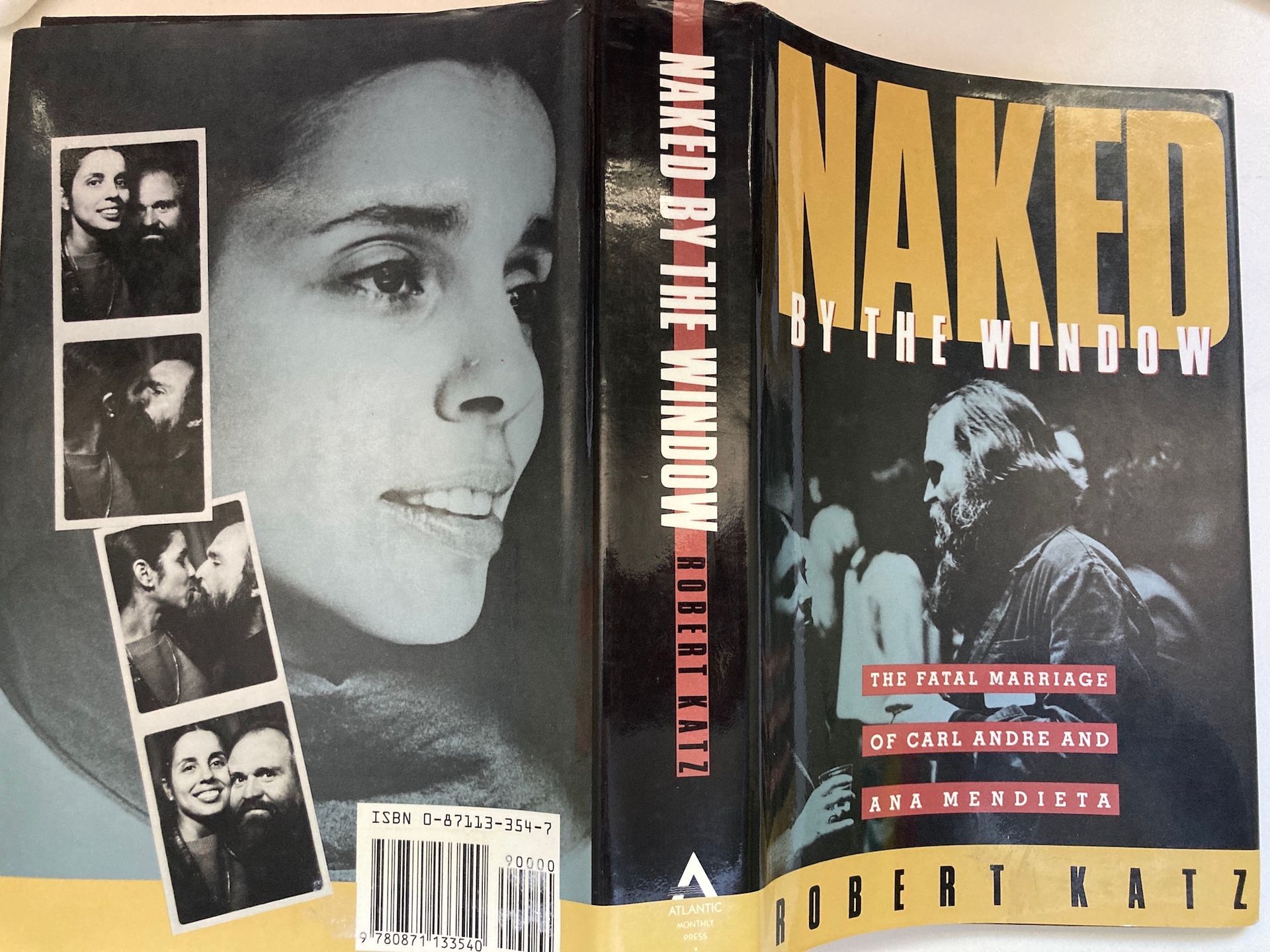

The question will not go away. Did the celebrated minimalist sculptor Carl Andre kill his wife, the up-and-coming artist Ana Mendieta, by pushing her out of a 34th-floor apartment window in 1985? Andre was tried and found not guilty of second-degree murder, but investigative reporter Robert Katz gave us plenty of reasons to doubt that verdict in his 1990 book Naked by the Window: The Fatal Marriage of Carl Andre and Ana Mendieta.

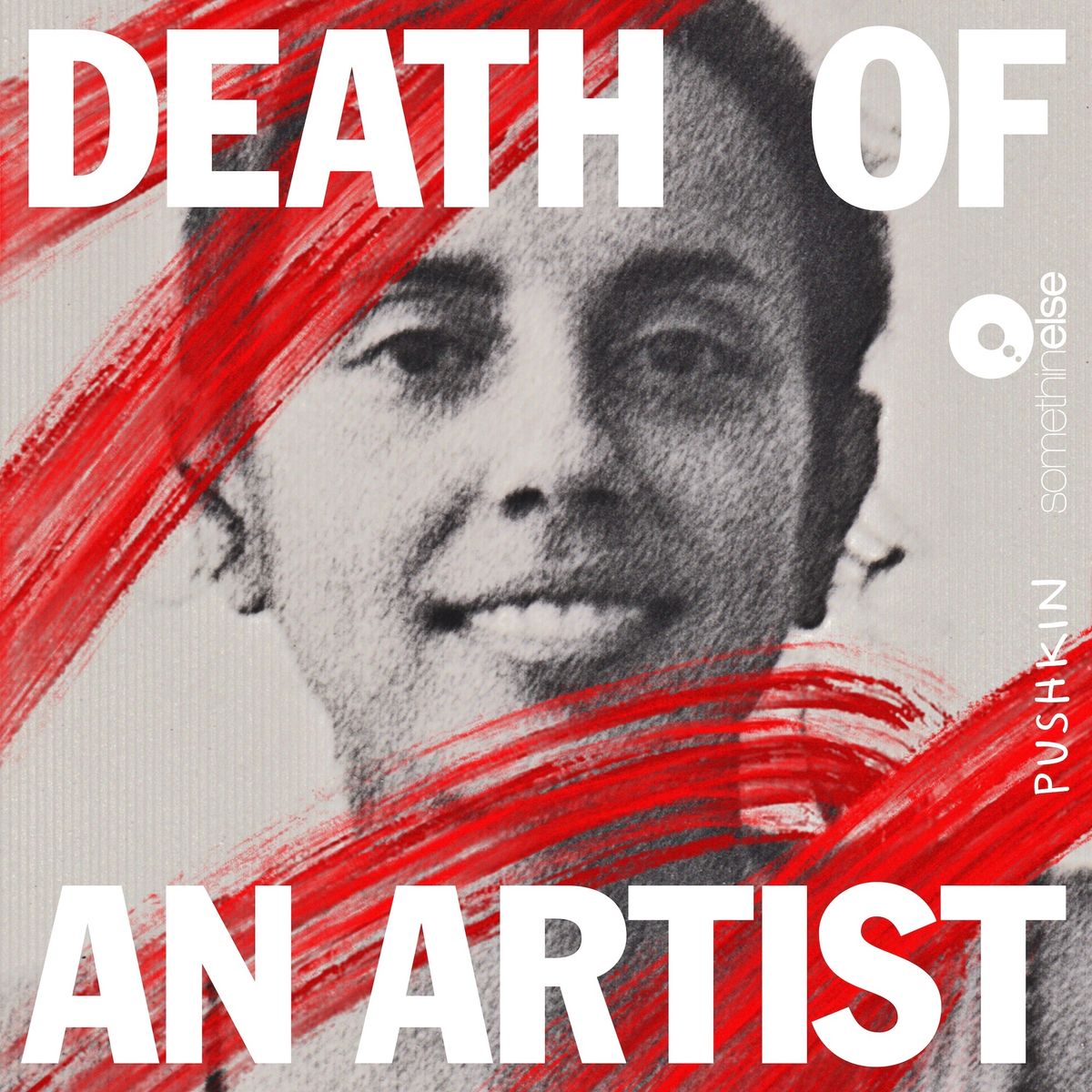

Now, curator Helen Molesworth revisits Mendieta’s death, Andre’s trial and the way it divided the New York art world in her new podcast Death of an Artist. Don’t expect much by way of journalistic bombshells. In his book, Katz already covered in great detail the scratches seen on Andre’s face the next day and the inconsistent excuses for them. And he shared evidence that wasn’t allowed in court: most notably, Mendieta’s plans to divorce Andre, which she discussed by phone with a close friend in Andre’s presence (though mainly in Spanish) the night of her death.

But Molesworth is a thoughtful, powerful storyteller and the six-part podcast, which uses audio clips from Katz as well as new interviews, proves in some ways even more compelling than his book. She tells the story of a brilliant, boundary-pushing, woman artist who was punished in some quarters for being too ambitious or strong-willed (which Molesworth intimates that she knows something about, having been pushed out at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles). And she uses the great divide between Andre and Mendieta supporters to show how the art world operates by carefully curating and silencing stories to create the illusion of consensus.

Death of an Artist is a moving portrait of Mendieta as a Cuban-American artist, wife, friend and crime victim. It is also a chilling portrait of the conspiratorial real-world silences that compound the art-historical neglect of women and people of colour.

Helen Molesworth, host of the podcast Death of an Artist Photo by Brigitte Lacombe

Jori Finkel: My sense is you’ve retold Ana Mendieta’s story for a #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter era, a time when we’re more aware of gendered and race-based power struggles and also domestic violence. Is that why you felt it was important to take a fresh look at her story?

Helen Molesworth: Yes, absolutely. I, like almost everyone, have been in the throes of a rethinking a lot of the things I learned in school. One of the things this period has done is shown us the blinders of our education, the lies of our education, and if we’re going to think seriously about how white supremacy is structural and systemic, then you have to go back and unpack everything. In that spirit, the story of Carl Andre and Ana Mendieta offers us a case study that lets us really test some old ideas and new ideas, and the cultural sea-change in how we think about domestic violence makes this story very different than the way it was told in the late 1980s.

Yet it’s still not an easy story to tell. According to one of your sources, B. Ruby Rich, the assistant district attorney prosecuting Andre in the 1980s said she had “never encountered a wall of silence like this one except in mafia cases”. It sounds like you hit that wall of silence too.

We did. When I took on the assignment, I very blithely assumed that everyone would be willing to talk—surely people will talk to me, people will trust me—and that was not true. [Laughs]. I also thought that because Mendieta is now such an essential figure, people would be more willing to talk. I could understand a little why people didn’t talk in the beginning, when the New York art world was smaller and Andre had so much power. Time’s passage did not loosen any tongues, and that’s perplexing to me. Some of Mendieta’s friends found it too painful to revisit, and people surrounding Andre still had iron-clad silence.

And Carl Andre himself has been silent about her death for decades—not just with you but with almost everyone.

Yes, he’s basically said four things, all of them contradict one another, and he won’t speak to that either. Nor will he acknowledge the gravity of the loss.

And you had no response from Andre’s longtime gallerist, Paula Cooper?

Paula also declined to be on the podcast.

Did she have any explanation?

No she did not.

Who else did you most want to speak with for the podcast?

I wish Lucy Lippard would have talked to us—she was both an Ana Mendieta and Carl Andre supporter, but her position was, I’m looking to the future and that was the past. I understand that, but I think there is an irony there because one of the central questions of Ana Mendieta’s work is what kind of viewer you are going to be: are you going to be a witness or are you going to be a bystander?

It seems like the key facts that you share in the podcast come from or back up Robert Katz’s reporting in Naked by the Window. But maybe I’m missing something. Is there any case where you turned up something materially different, factually different, than Katz?

No. When we first took on the job—I was teamed with producer Maria Luisa Tucker, who was trained as a journalist—there was some sense this was a cold case file and that we might be able to do some hard-nosed investigative reporting. But because of the nature of Andre’s trial, a bench trial and not jury trial, when he was acquitted he was able to seal all of the documents. That’s everything from the audio of the 911 call he made to the court transcript to the Polaroids taken at Rikers by the cops that show scratches found on his body. All of that material is sequestered and cannot be seen, not even a Freedom of Information Act request can open the files. Only Carl Andre has the power to unseal those documents should he wish.

The cover of Naked by the Window: The Fatal Marriage of Carl Andre and Ana Mendieta (1990) by Robert Katz, whose reporting was the basis for the new podcast Death of an Artist. Photo by Jori Finkel

But you were able to use Katz’s interviews for Naked by the Window?

His family generously allowed us to access his archives at a small library in Tuscany [where he died in 2010]. We didn’t go to Italy because of the pandemic but listened to reams of archival audio,over 200 interviews. When you’re hearing Leon Golub and Nancy Spero, Lawrence Weiner and Sol LeWitt, those are the archival recordings we digitized.

I loved the bits with Sol LeWitt and his wife. They were friends with Andre but don’t make him sound very sympathetic.

That’s true of a lot of Andre’s friends: they are gimlet-eyed about Andre being a difficult person, especially under influence of alcohol. We also came across people who knew Mendieta and found her difficult. This is the case of two big personalities who when fueled by alcohol became really demonstrative with each other. Alcohol plays a huge role in their particular story—and in the art world, where servers are walking around with an endless pour. We exist as a highly social formation and that formation in the evening is fueled by booze. I used to drink a lot myself, and alcohol is a very powerful drug.

My takeaway is that you are convinced of Carl Andre’s guilt, but you fall short of calling him guilty in the podcast. I assume that’s for legal reasons?

Yes, for legal reasons I can’t say that he’s guilty because he was acquitted. What I’m more interested in personally at this point, having done the podcast, is how our legal system is structured by a huge flaw. We now understand that almost 90% of women who are murdered are killed by intimates, husbands, boyfriends or someone else they know. But if there is no witness, our legal standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt” leaves a woman, and that includes anyone who identifies as a woman, which is to say the less powerful person in the dyad, without recourse to the truth.

We also now know that women are more likely to be murdered by their partners when they’re in the process of leaving, or have just left, than any other time in the relationship; it makes up around 75% of all domestic violence homicides. I kept waiting for you to mention this when you were talking about Nicole Brown Simpson and O.J. Did you come across this fact?

I didn’t know that statistic specifically but it does not surprise me. We know that Ana Mendieta was leaving Carl Andre. We know this through the testimony of one of her closest friends: there was a final fight and Ana dies at exactly the time she is trying to leave.

It was great to hear another Cuban artist, Tania Bruguera, reading the statements made by Ana Mendieta on your podcast. What gave you that idea?

There’s almost no audio of Ana Mendieta. What little audio exists is embargoed by the estate and they’ve never given anyone permission to use it. Here you have someone who has literally been silenced, had her voice taken away, how do you not repeat that silencing in your storytelling? At a certain point we were trying to sprinkle quotes of Ana’s throughout the podcast to give listeners some sense of the character of her mind. I was reading them and it felt off and strange, I didn’t know how to shift my voice from the narrator to Ana’s voice. It didn’t feel appropriate.

Tania had redone Ana Mendieta’s performances and seems like the inheritor of so many of her ideas, and she very graciously agreed to record her voice for the podcast. Ana was essential for opening relationships between artists in Cuba and the US, creating a pipeline to this incredibly rich society that had been forcibly cut off from rest of world. And when she encountered injustice, she was someone who spoke out; Tania follows in her footsteps not just aesthetically but also at the level of personal bravery.

You also explore the role of racism in her trial, how the lawyers smeared Mendieta for her interest in Santería, painting her as a witch or voodoo practitioner. Coco Fusco called it an “utterly racist interpretation of her work”.

Here you have an artist from Cuba who is investigating in a very thoughtful way the images and belief systems that are attached to Santería, a highly evolved religious world view, and it’s treated at the trial as a form of mental illness. It’s really gross stuff. I would like to think that should such a trial take place today somebody would call bullshit on it.

Mendieta’s own artworks, and her use of blood in her work, was used against her in court, as if she had a death wish. But you start the first episode by describing in graphic detail a bloody art installation she made in Iowa City in response to a campus murder and rape (Moffitt Building Piece, 1973) as if it’s an actual crime scene. Were you concerned that this approach might sensationalise her death?

No, I was not. I think we tried very hard throughout the podcast not to sensationalise her death, which was very horrible, and we didn’t include plenty of details. We started with her work to give listeners a narrative arc through her career—and we end the podcast with one of her last works.

The other reason we wanted to start with Moffitt Building Piece is because it raises the central question of her work, about your role as a human being on this planet. What are you going to do when you encounter injustice, whether a rape, the residue of violence or an endangered landscape? I think that’s overlooked in Mendieta’s work but she could see the beginning of what we now know as a full environmental crisis, just as she was sensitive to the abuse of women’s bodies under patriarchy.

The lead producer on your podcast was Pushkin Industries, the company co-founded by writer Malcolm Gladwell. How did that come about?

Jacob Weisberg, the other founder, approached me because he heard [from Lucas Zwirner, David Zwirner’s son] I was someone who spoke about art in ways that people can understand. He asked me if I would like to take on the Mendieta and Andre story. It has all the components of a great story: a crime, potentially a crime of passion, opposites attract, the world within the world of the art world, and artists who live outside of normal conventions and arrangements. And true crime is the number one driver of podcasts.

You begin and end your series talking about the artist vs. artwork question, what I always think of as the Woody Allen question. Can you still enjoy the artwork of an artist you find personally reprehensible? I for one can’t and won’t watch Woody Allen films anymore, but you came to a different sort of conclusion.

Well, I’m all over the place about it. I too don’t think I could watch a Woody Allen film right now, but I feel a great deal of sadness about that. I love the films Manhattan, Hannah and Her Sisters, Annie Hall, but is my love of them worth voting with my dollars on Amazon Prime to watch them? Do I need them to get through the day? No, I do not.

It seems like every project these days aspires to become a streaming series for HBO or Netflix or such. Has there been any talk of turning this into a series?

I think lots of people have been trying to figure out how to tell Ana Mendieta’s story in a televisual form and nobody has figured out how to crack that case. Hollywood has not really been successful at portraying the art world, hence people in art world are skittish about selling their rights to Hollywood.

Do you have a favorite true-crime podcast?

No, I don’t listen to true-crime podcasts. I listen to cultural podcasts like Scene on the Radio and Still Processing. Although truth be told I did go down the Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell rabbithole a couple years ago.

- Death of an Artist, produced by Pushkin Industries, Somethin’ Else and Sony Entertainment, Begins streaming on 23 September.