Experiencing Andy Warhol: Three Times Out at the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin brings to mind a remark that the art critic Bernard Berenson once made to the historian Iris Origo as they walked through the Tuscan hills a century ago. “One moment is enough,” Berenson said, as he talked of the art of looking, “if the concentration is absolute”.

That quality of absolute concentration presents itself in moments short and long in the spacious, unhurried installation mounted by the curators Barbara Dawson and Michael Dempsey at the Hugh Lane. It stands out in Warhol's fastidious concern with colour, with memorialising and mortality; his mastery of studio process (where, like Auguste Rodin, he found inspiration in “doing the work”); and in the unflinching way he used self-portrayal and self-mythologising to create an epoch-defining take on the artist's life. Then there is Warhol the history artist who saw through the workings of news media in the days of 1960s protest; and the film director who played the unblinking voyeur of sleeping, eating, gossiping and lovemaking.

Andy Warhol Three Times Out includes more than 250 works by the artist, lent by the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh and by institutions and private collectors from the United States, Canada, Ireland and beyond, covering almost the full gamut of his output: drawings, paintings, screenprints, film and photography. Such is the scale of the exhibition that elements of the gallery's permanent collection have been moved to accommodate the show, which is spread across 16 of the Hugh Lane’s 26 galleries.

Beautiful, abundant and strangely heart-breaking: One of the walls of early drawings in Andy Warhol Three Times Out, at the Hugh Lane Gallery, in Dublin © 2023 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / IVARO, Dublin, 2023. Photograph: Denis Mortell

An art-loving artist who hid his own talent

The exhibition opens in a dark-walled room with a facsimile of Warhol’s Silver Clouds (1966)—helium-and-oxygen-filled balloons that float and bounce—followed by an arresting sharpening of focus in the lofty and light second room, where a closely hung selection of 75 drawings from the 1940s and 1950s hang on facing walls, with a broad expanse of Warhol’s Mao Wallpaper on the intervening wall.

Many of the drawings were not exhibited at the time of their creation because of their homoerotic content; while a large number were put away during Warhol's life and have come to light through the exhaustive cataloguing of the artist's work since his death. Collectively they demonstrate Warhol's beguiling economy of line—something that served him well in his first career as a successful commercial designer. It is a room that reveals both Warhol's natural gifts as a draughtsman, and the first stages of his effort to disguise them, through developing a blotting technique and other methods of tracing and reproducing work. Robert Rauschenberg once commented that “Andy had a kind of facility which I think drove him to develop and even invent ways to make his art so as not to be cursed by that talented hand.”

This cornucopia of early drawings, beautiful, abundant and strangely heart-breaking, is a place to return to after seeing the rest of the exhibition and is alone worth the price of a ticket to this grandly paced exhibition.

Working against a medium designed to capture movement: installation shot of Screen Tests, 1964-66, in Andy Warhol Three Times Out, Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin © 2023 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / IVARO, Dublin, 2023. Photograph: Naoise Culhane

Warhol the film-maker

That “talented hand” would later turn to film, exemplified here with digitised versions of Sleep (1963, five hours and 21 minutes long) and Empire (1964, eight hours and five minutes), which give the long-form film director Warhol full due in their mesmeric, time-agnostic, flickering, silver-grey monochrome. Seeing Sleep is a reminder that, during the editing process, Warhol asked to have sections removed where the model, his then partner John Giorno, shifted in his slumbers. “He wanted,” the film's editor, Sarah Dalton, recalled, “the movie to be without movement”. It was also projected in slow motion, to create a dream-like scene.

It feels as if Warhol was fighting a conscious battle with time (and tempo) and against the central virtues of a medium designed to capture light and movement. This is even more apparent in the compelling array of 15 of Warhol’s 363 four-minute camera-roll portraits from the mid-1960s, the Screen Tests. Here, the Warhol superstar Edie Sedgwick, the artists Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dalí, and the actor Dennis Hopper, gaze into the camera, their face muscles as still as they may be. A hyper-chatty, hyper-mobile “test” by the singer-songwriter Bob Dylan is the exception that proves the rule.

Installation shot of four Jackie paintings by Warhol and Jackie (Gold) 1964 © 2023 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / IVARO, Dublin, 2023. Photograph: Naoise Culhane

The silkscreen paintings series

The highlights of Warhol’s silkscreen painting series are chastely and spaciously hung against the white-cube walls of the gallery’s 2006 extension. The series include early dollar bills (his first silkscreen paintings), Campbell's soup tins and Brillo boxes; portraits of movie stars like Marilyn Monroe and world leaders such as Richard Nixon and Chairman Mao; the news-driven history paintings of the Sing Sing prison electric chair; and still lives of flowers, skulls, hammers and sickles.

That spaciousness allows both room and time to feel the beauty of colour and gradation in Warhol's work, notably in a compelling series of the Electric Chair paintings, and a sequence of Jackie Kennedy images—first happy then bereft in the aftermath of John F Kennedy assassination in 1963—as the gradations of blue lead to gold. This last image feels like a nod to the gold ground colour of the icons that populated Warhol's upbringing as a member of the Byzantine Catholic church.

Spectral shadows: installation shot of Warhol self-portraits, in Andy Warhol Three Times Out © 2023 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / IVARO, Dublin, 2023. Photograph: Naoise Culhane

The exhibition includes an evocative selection of the self-portrait photography, projecting the auto-myth of the white-faced, blank-visaged, bewigged Warhol, seemingly affectless and emotion-free—from the 1963 photo-booth shots of a beefy, Brando-like Andy in shades, to giant, gaunt 1986 fright-wig extravagances, via the 1981 Shadow series that casts a wildly stretched, spectral, shadow of the Warhol profile.

On-register colour: Francis Bacon, Kneeling Figure Back View (c1982), left, and Andy Warhol, Skull (1976) Bacon: © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved / DACS London / IVARO Dublin, 2023. Warhol: © 2023 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / IVARO, Dublin, 2023. Photograph: Louis Jebb.

A brother in colour with Francis Bacon

The exhibition merges at the farthest point from its start with the Francis Bacon Gallery—a room that adjoins the Dublin-born Bacon's beautifully preserved and lit London studio, transplanted to the Hugh Lane in 1998—where two of Warhol's small skull paintings from 1976 are hung, to powerful, complementary, effect, with a group of large canvases by Bacon from the gallery's permanent collection. Here, the intense cyan and orange acrylic background of one of Warhol's skulls is on-register with the neighbouring cadmium orange of Bacon's Kneeling Figure Back View (around 1982). It is a thrilling conjunction that brings Warhol the master of colour to the fore.

A parallel curatorial point is made in another exhibition, hung in a similar-sized room, that opened at the same time at Ordovas Gallery in London (until 15 December). There, the colour worlds of Warhol and Bacon complement each other to no less ravishing effect in the loan show Endless Variations. Warhol once happily claimed that he had appropriated both Bacon's colours and his skulls; while Bacon expressed an admiration for Warhol’s Accidents: “I like the ones in various colours of the Electric Chair”. In a catalogue essay for Endless Variations, Martin Harrison, editor of the Bacon catalogue raisonné, reveals that he had discussed the idea of a joint exhibition of Bacon and Warhol with the late great art critic and curator David Sylvester while the latter was preparing his Looking Back at Francis Bacon (2000), in which Sylvester wrote: “The artist whom I want to see alongside Bacon is Warhol.”

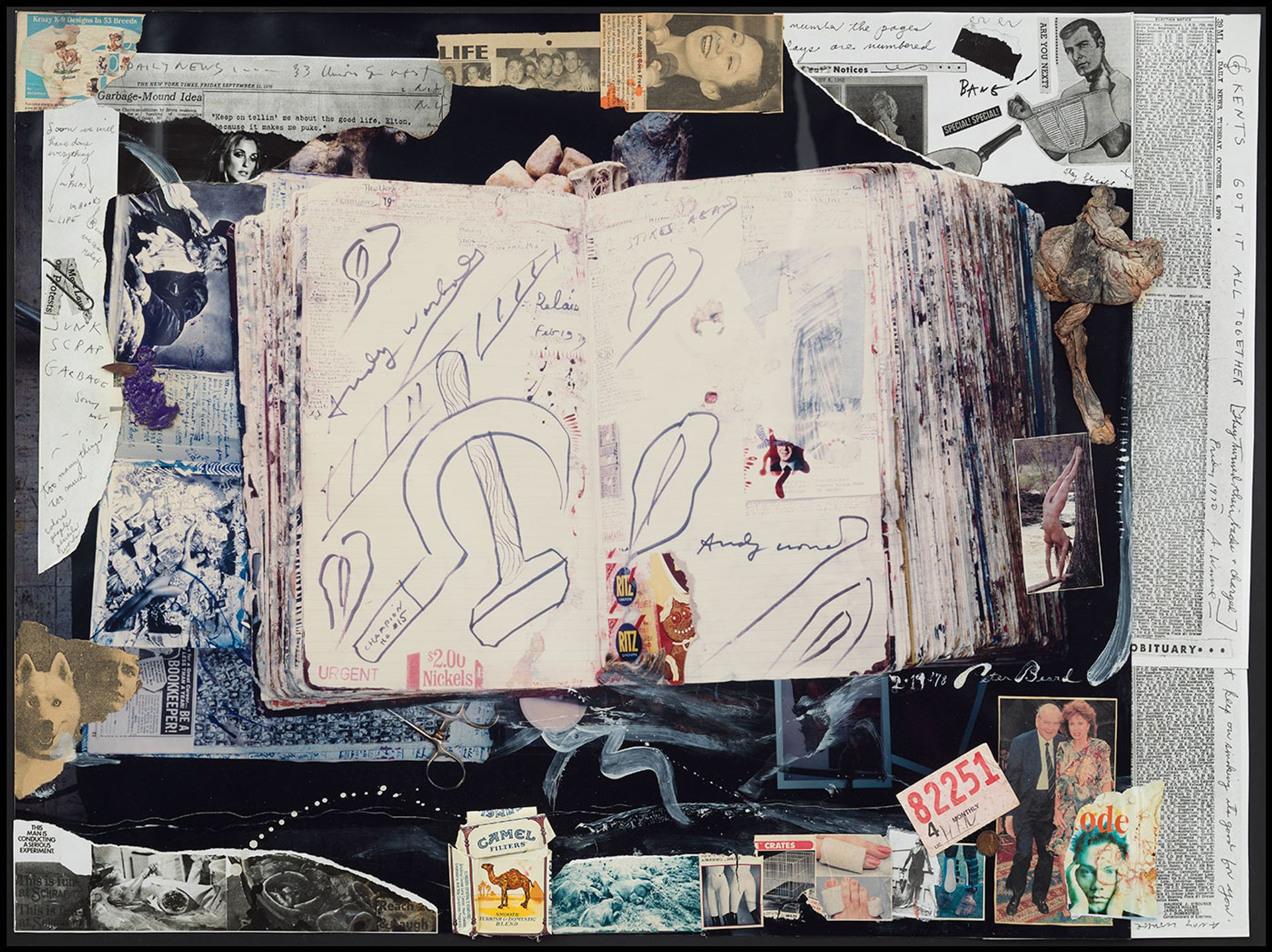

A heady array: installation shot of 17 pages from Andy Warhol and Peter Beard’s 1970 collage series An Introduction to the Things of Life. Warhol: © 2023 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / IVARO, Dublin, 2023. Beard: © The Estate of Peter Beard, 2023. Photograph: Louis Jebb

Warhol-Beard-Bacon: a creative and emotional sweetspot

At the Hugh Lane, the Bacon and Warhol gallery gains a powerful added narrative from two neighbouring rooms of collaborative works. In one there hang 17 pages from Warhol and the artist and photographer Peter Beard’s 1970 collage series An Introduction to the Things of Life, a heady array of newspaper and magazine cuttings, images of disasters and the two men’s jotted squibs, meditations and sketches—with a tiny waving Warhol disappearing into an open Campbell's soup tin a particular delight. They project a touching collaborative vim, derived from what Warhol dubbed the two men's “creative playtime”, in a room that also features Warhol and Basquiat’s skull-ridden Poison (Collaboration No. 62) (1984) and Warhol and Keith Haring’s 1985 Untitled (Madonna: I’m Not Ashamed), based on a New York Post front page.

In the second room, a beguiling assemblage of Beard’s photographs of Warhol, and their diaries and jottings create a moving portrait of a Warhol open to artistic collaboration with Beard, whom he considered “one of the most fascinating men in the world”. In these fascinating records of the decades-long friendships that Beard maintained with both Warhol and Bacon, there exists a Warhol who sits creatively and emotionally at a sweetspot between the legendary presiding master of young talent, video makers and silkscreen assistants at his Factory studios in midtown and lower Manhattan, and the happy party boy who accepted every dinner invitation he received from Mick Jagger and Jerry Hall.

Andy Warhol and Peter Beard: 78 Diary (@ lunch Feb. 19 / Le Relais on 63rd and Mad. Avenue) Warhol: © 2023 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / IVARO, Dublin, 2023. Beard: © The Estate of Peter Beard, 2023

The Warhol-Beard room also contains an arresting example of their unselfconscious, shared, creativity in the shape of Warhol’s 1978 line drawing of a hammer and sickle in one of the collaborative pages he worked on in Beard’s highly annotated and collaged diaries (Warhol called them “trip books”). The page carries the evocative inscription “’78 Diary (@ lunch Feb. 19 / Le Relais on 63rd and Mad. Avenue)”. Warhol's drawing, with its pure, bold line, takes the visitor associatively back through the exhibition, to the graphic verve of the early drawings, to the big hammer and sickle still lives at the heart of the show, and to a 1976 film by Vincent Fremont, Andy Warhol, Andy Mops a Hammer & Sickle. This last is an example of the important work Warhol's videographers did in capturing the artist at work—the "mopping" being the artist's gestural use of a floor mop to paint on a grand scale.

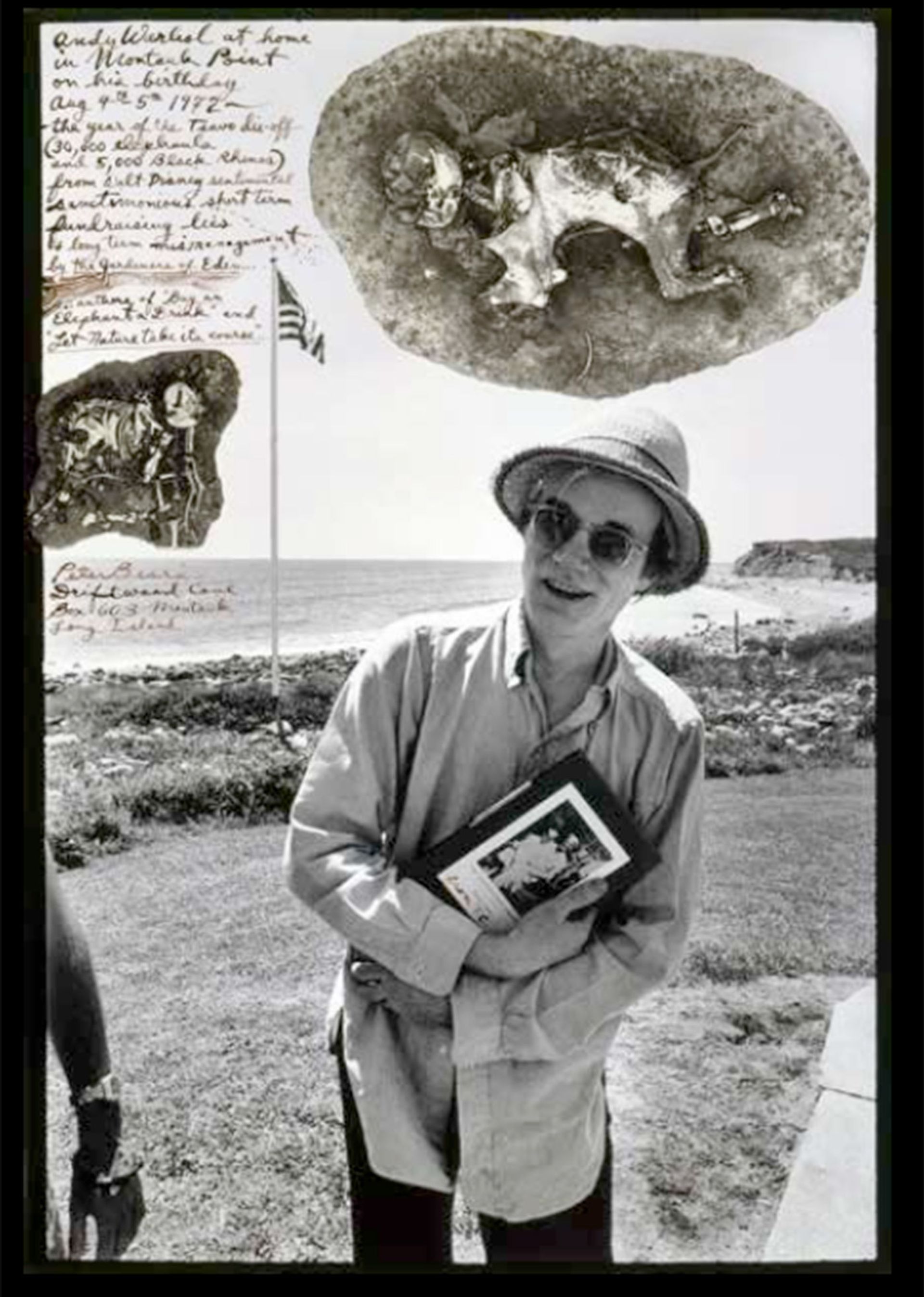

Unabashed Andy: Peter Beard, Andy Warhol at home in Montauk Point on his Birthday, August 4-5. 1972

Portraits of the artist in the wild

In the Warhol-Beard room there is an important, revealing set of large-format collaged images that Beard, a master of wildlife photography, took of Warhol in 1972. Among these is one taken at Montauk Point, around Warhol’s birthday, where he is pictured clutching a book, a present from the writer Truman Capote, and sporting a shy but unaffected smile. It is a charmed, unabashed moment that takes the viewer back to a photograph of a beaming young Andy, in a happy family group in working-class Pittsburgh, where the frail but smiling artist prodigy, chronically ill for much of his childhood, is surrounded by his parents and his more robust elder brothers.

There is a palpable sense, in this group of Beard's photographs, of emotion first building and then getting out, allowing us to see a sensitive, off-duty, and nurtured, side to Warhol—the obverse to the image-aware visage of the public-facing creative general.

A charming diversion: Andy Warhol's Silver Clouds (1974) in the act of escaping in to the room of early drawings, in Andy Warhol Three Times Out © 2023 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / IVARO, Dublin, 2023. Photograph: Naoise Culhane

Silver linings

Andy Warhol Three Times Out has been put together with an eye for quality and completeness, but that very completeness means that not everything can be as compelling as his early drawings, the best silkscreen paintings, the Screen Test films, the in-the-ether connection with Bacon, or the historic collaborations with Beard, Haring, Basquiat and Clemente. Silver Clouds has been an unavoidable staple of Warhol surveys since the first at the Museum of Modern Art New York (MoMA) in 1989, but, in the context of such an absorbing installation, these silvery pillows are a charming diversion, but cannot bear the Abstract-Expressionist-artist-taunting importance sometimes assigned to the work.

Warhol's late camouflage works lack interest unless they are deployed in the act of camouflaging something, as when layered to dramatic effect over Leonardo's Last Supper (a piece included in the lockdown-affected Andy Warhol at Tate Modern in 2020) or a Warhol 1986 fright-wig self-portrait (the entrance sentinel at MoMA, 1989). For that reason, Camouflage (1986)—four canvases with an identical pattern repeated in four interesting colour combinations, but disguising nothing—feels short of purpose when hung at the heart of the Hugh Lane show opposite a virtuoso array of the artist's self-portraits.

Three’s a charm

Andy Warhol Three Times Out is a show that you might see the titular three times and still feel you have only begun to scratch the surface of what is to be discovered in such a broadly based, undogmatic survey of the artist's work; of his explicit connection to the history of art, both past and contemporary, and of his deeply considered experimentation around repetition, scale and, above all, colour.

The organisers have presented rich context for still-unmined areas of Warhol's life—notably the Beard and Bacon collaborations—but have eschewed over-curation, and the temptation to favour one period of Warhol's career over another, or indeed to look for a topical 2020s relevance. (The Donald Trump strand explored in Warhol from A to B and Back Again, the magisterial survey at the Whitney in 2018-19, felt like a distraction at the time and has not aged well since.)

Indeed, by getting out of the work's way, the curators have allowed Andy Warhol the student of art and artists—the most familiar, best archived, most successfully self-mythologising, and unavoidable practitioner of the late 20th century—the space to continue to surprise with art that, in the flesh, remains unmissable and like no other; and to inspire and reward (the viewer’s) absolute concentration.

What the other critics said

In The Times, Pat Carty deems the exhibition “a glorious exhibition that will erase preconceptions about the artist.” In Cent Magazine, Jo Phillips focuses on the importance of Warhol’s early drawings, describing them as “sharp, questioning, enquiring, yet also painful, and immensely personal”. She adds that “these seemingly inconsequential” drawings provide Warhol’s better known works with “a new dimension”.

Ksenia Samotiy, writing in the Irish Independent, has a more existential take on the show: “With AI now being able to produce art at the click of a button, we are again left wondering about the future of art. The scale of Three Times Out hints at how Warhol might answer: the future of art is whatever we want it to be, or rather whatever we make it. And like the exhibition itself, that question is deeply emotional, enigmatic and exciting.”

• Andy Warhol Three Times Out, Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin, until 28 January 2024

• Curators: Barbara Dawson and Michael Dempsey