Warhol from A to B and Back Again (until 31 March 2019) at the Whitney Museum is essential viewing. It is big and sprawling, but Warhol, from the early 1960s until his death, was a cultural constant, so “everywhere” that I felt I had lost someone I knew well when he died. A great strength of the show is Warhol’s presence throughout as not only a personality but as a man. He ages, grows, experiments, tries and fails. He was an insider, a social whirl, and a star-maker, but he was an outsider, too.

He was both unserious—his art is often silly, colourful, teasing and sardonic—and deadly serious. His disaster and electric chair pictures from the early 60s are edgy and disturbing, even after more than 50 years. His very durability grew from, of all places, the ephemeral, whether it was personal fame, products that waxed and waned in popularity, fads in music or fashion, magazines, films, the Factory party scene, or images produced in so many millions they seemed to peter out in fragments.

The show is a needed revisit for those of us who remember Warhol as a living, brilliant savant, taste-maker and oddball. Since Warhol died in 1987 and is now a historical figure so, a new generation or two also needs to experience him. And as the museum’s director Adam Weinberg says, this is the magnum opus of the Whitney’s senior curator Donna De Salvo. One of the great scholars of postwar American art, which for all practical purposes was anchored in New York, she has a thorough, nuanced knowledge of Warhol and his time.

So the show is an overview but also a serious, demanding class. There is the art on the walls and the labels, but the audio component is fascinating. A show about the founder of the magazine Interview, the self-described “crystal ball of Pop”, has to have good interviews. They are better than the labels, more informal and anecdotal, and they are more likely to get us into Warhol's head and his time.

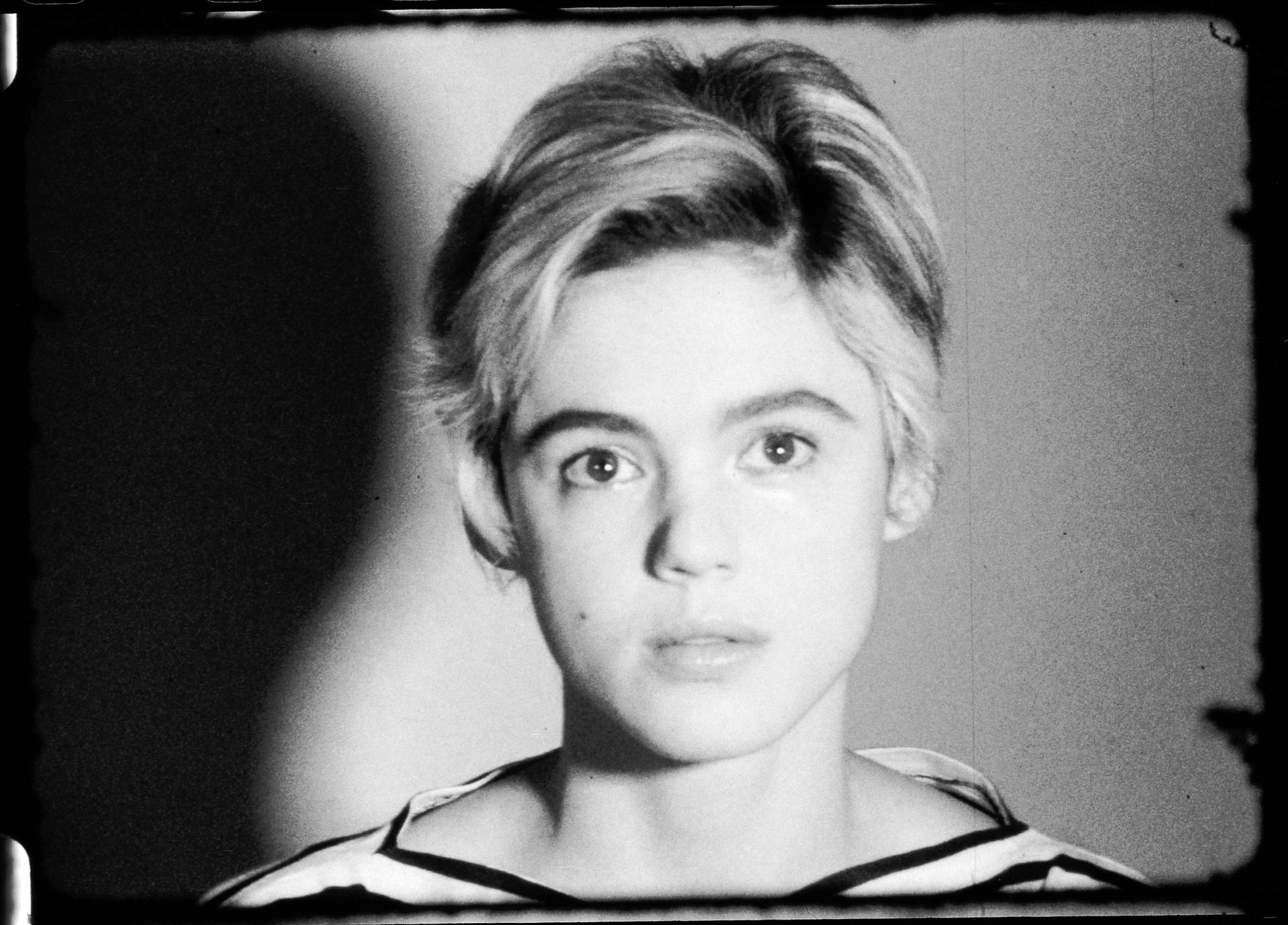

Andy Warhol, ST309 Edie Sedgwick (1965) 16mm, b&w, silent, 4.5 min @ 16 fps, 4 min @ 18 fps Pictured: Edie Sedgwick. © 2018 The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved

Warhol's films are essential viewing, too. They shatter the notion that the artist was most concerned with the quick glance, the superficial take, or the air-brushed, glam icon. The films are claustrophobic, as Warhol’s camera often fixes on a subject for many minutes. The longer we look, the more we see and the more we imbed ourselves in the image. The sun never intrudes; it is an after-hours world. That Warhol was a voyeur is beyond a reasonable doubt. Putting that creepy psychology aside, we see him in the films as an artist more than willing to put his subjects under a microscope.

The show cannot be everything, however, and the Whitney is only so big. It tells us often that behind all of the art was the visionary Andy Warhol, a workaholic and eternal tourist who saw the otherness in everyone. This is good. For Warhol, biography is vital.

It seems to me he had four anchors. First, Warhol was a creature of the Depression and the Second World War, which surely add a different dimension to his take on the new and shiny things that post-war prosperity gave us. As any baby boomer can tell you about their parents, the 1930s and the war could not be transcended.

Second, Warhol was gay, and it is hard to see his art clearly without the context of gay New York in the 1950s through to the 1970s. He was no virgin but part of a world growing less closeted by the day. The show is frank about his sexuality, something earlier shows avoided. The catalogue is strong here, with great essays by the artist Glenn Ligon, a superb writer, and the Andy Warhol Museum curator Jessica Beck. A fine take on his late Camouflage Last Supper, positioning it as Aids art, would have persuaded me to think the picture was good had I not actually seen it. The scholar Trevor Fairbrother’s essay is more expansive, touches on this subject, and is elegant, substantive and to the point.

Third, Warhol was raised in working-class Pittsburgh. The WASPY, radical chic Edie Sedgwick probably was as weird to him as drag queens such as Candy Darling, or real queens like the Empress of Iran. Warhol was too smart to think he could drop his roots and, in any case, kept in close touch with his family. What did these basic experiences—family, hard times and war—mean to him and his art? Finally, Warhol was, believe it or not, deeply religious. Most mornings, he went to church, he took it seriously.

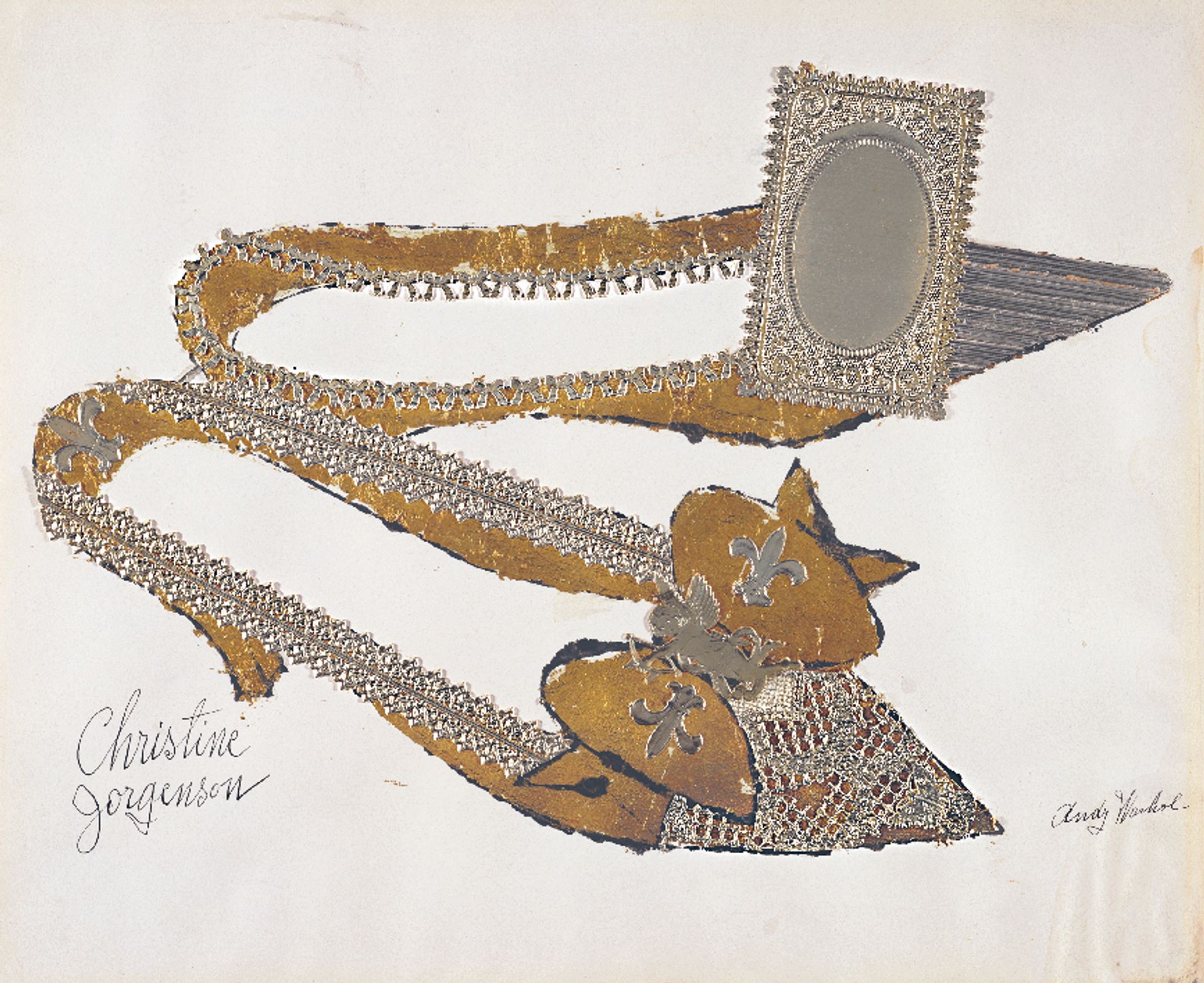

Andy Warhol, Christine Jorgenson (1956), collaged metal leaf and embossed foil with ink on paper Sammlung Froehlich, Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

For a time in the 1960s, Warhol was a revolutionary artist, but his revolution was in large part a restoration. He came from the world of commercial art, where in the 1950s he was a big success. So did Winslow Homer, most of the Ashcan artists, and many of the American Modernists of the 1920s and 1930s. The elite art world of the 1950s and 1960s scorned artists who slummed it on Madison Avenue, but Warhol was innately business-minded. He was mostly unashamed and understood that the prevailing winds in American culture blew over the land of buying and selling. After a decade of Abstract Expressionism, an aberration, Warhol was the one who recovered the dominant representational strain in American art dating from John Singleton Copley.

The Whitney show is very much about the awkward periods when Warhol was not “mostly unashamed”. Warhol was a transformative artist for a very short period. His works from the late 1970s and early 1980s, like his Camouflage Last Supper and the big oxidation pictures where he mixed paint with urine, are not very good. He was trying to be what he was not, which was a high-brow abstract painter. It is the understandable craving of a working-class kid to ascend an ivory tower towards a zenith of taste, achievement and refinement. He was addicted to social climbing. Trouble was, he had nearly single-handedly demolished the culture's fleeting fancy for art with no discernable subject à la Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline and Barnett Newman. He was deeply aware of the critical wall between high and commercial art, a wall he strove to scale but instead helped to demolish. This is a very good thing since the wall was built mostly by snobs.

Another theme, mostly in the catalogue, is the ever-present shadow of Donald Trump. This is a distraction. The complete infestation of US politics with a celebrity complex would have surprised Warhol only in taking as long as it did. It started in the early 1960s, with the Kennedy Rat Pack, to entrench itself in what had been a realm of boring old yahoos, Yankee patricians and tinpot despots from everywhere but Hollywood and New York. Warhol was a lot of things but a political philosopher he was not. Insofar as he had any conception of civics, it lay in his thorough understanding of advertising. He knew how to promote a product and how to milk every impulse in human nature tuned to glamour. He thought show business promotes “not what you are, but what the audience thinks you are”. Contemporary politics and the corporate news media seem to aim at this, and Warhol would have immediately understood it.

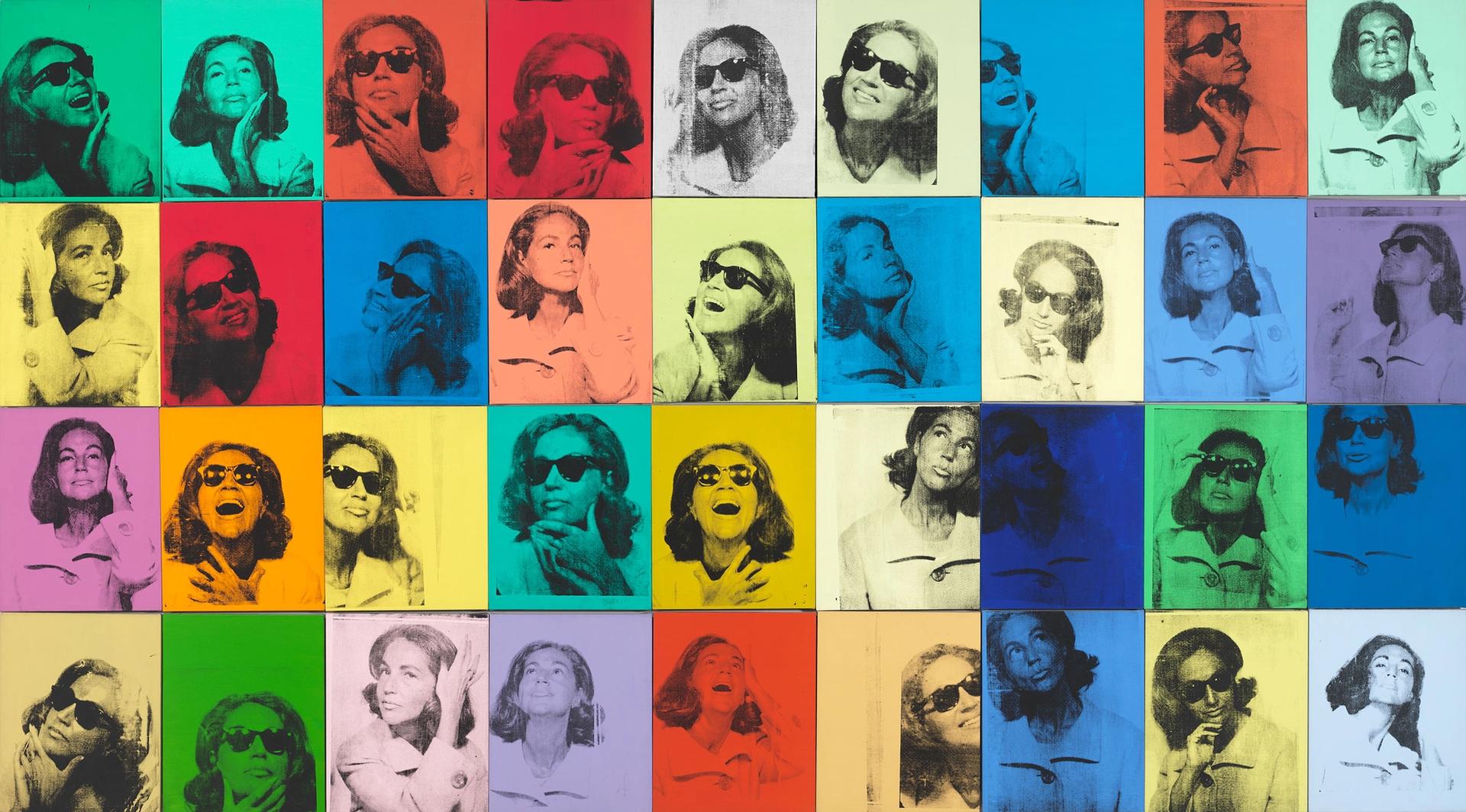

Andy Warhol, Ethel Scull 36 Times (1963) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; jointly owned by the Whitney Museum of American Art and The Metropolitan Museum of Art; gift of Ethel Redner Scull 86.61a‒jj © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

My advice for this show is just to look. It is beautifully installed. The section on Ethel Scull 36 Times from 1963 was one of my favorites, for sheer gorgeous art and the most buoyant of portraits. The story of Thirteen Most Wanted Men from 1964 speaks volumes on the times and Warhol, since it was at that point he entered the milieu of Philip Johnson, the king of opportunists, poseurs and insipid style. The portraits of Marilyn Monroe are surprisingly arresting. The section on Warhol on the cusp of becoming Warhol, the 1950s and early 1960s, is superb and priceless. He was a great designer in the early “mad man” days.

For those who do not remember the 1980s, Bonfire of the Vanities is a good access point. Published in 1987, the year Warhol died, it is a chronicle of a world he knew well, a world in which he was the ultimate flaneur. Warhol was a creature of his age, and by the late 1980s that age was, as the expression went, “so over”.