The Denver Art Museum (DAM), eager to purge traces of institutional deference to colonialism, last year removed all references to Christopher Columbus from its collections.

This spring, after a scathing exposé in its local newspaper, the museum excised the name of its late benefactor Emma C. Bunker from its Arts of Asia gallery, for which Bunker’s family had raised money. The museum also closed down an acquisition fund in her name. But Bunker would be a hard presence to expunge entirely in Denver, if the museum wanted to. Her memory is still a presence in other departments where she donated objects.

A veteran author on Asian art and a longtime donor to the museum, Bunker died in 2021 at the age of 90. Her father-in-law, Ellsworth Bunker, had been US ambassador to Vietnam from 1967 to 1973, when Richard Nixon ordered the bombing of Cambodia.

The reason the museum removed Emma Bunker’s name was because of her work with Douglas Latchford (1931-2020), a dealer based in Bangkok and a notorious smuggler of art who sold sculptures looted from temples in Cambodia and Thailand. She co-wrote books with Latchford on Cambodian art that experts now say were filled with false provenances.

Bunker was associated with the museum for decades, during which time she brought works purchased from Latchford into the collection. Four of those works have been returned to Cambodia. There could be more. The US Department of Homeland Security is said to be investigating sculptures (including one now in Denver) from a site in Thailand near the Cambodian border.

The veteran writer was herself known to law enforcement. In a 2021 complaint in US District Court targeting Latchford, and detailing Bunker’s own efforts to mislead investigators, federal prosecutors in New York called her “The Scholar” and, without naming her, identified her as a volunteer research consultant who “facilitated the sale and donation” of looted objects, “including by vouching for their provenance.”

Bunker was also called “The Scholar” and identified by name in earlier US efforts to recover looted objects from Sotheby’s in 2012, and from the dealer Nancy Wiener in 2011. In the latter case, Bunker provided a false provenance for a stolen bronze Buddha that Latchford sold to Wiener for $500,000.

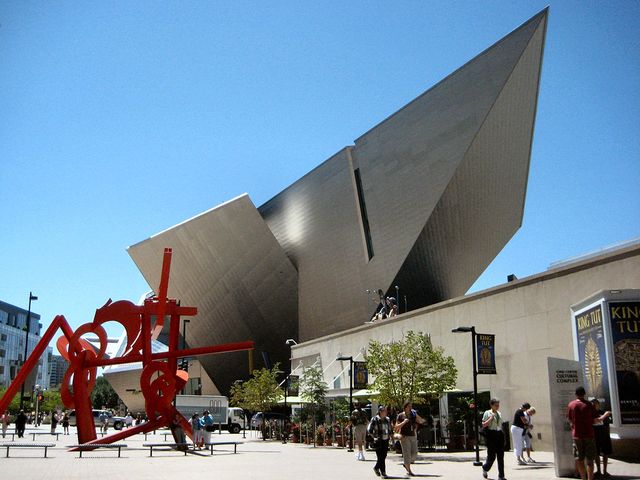

A detailed series on her double life, published by Sam Tabachnik in the Denver Post last December, brought this long-running cultural saga to a wider audience. His tale of Emma Bunker’s adventures with Latchford also brought the Denver Art Museum more attention than it has had since 2006, when it opened a steel building with shiny spikes designed by the architect Daniel Libeskind.

So has the museum now entered a post-Bunker era? Not if transparency is the standard. The institution turned down a request from The Art Newspaper to interview its director, but a press representative noted by email that “the museum’s collecting policies are in alignment with AAM and AAMD best practices, and have evolved in lockstep with the museum field… The Denver Art Museum is committed to ethical collecting practices, and has a track record of working proactively and collaboratively with US and foreign governments to return artworks proven to belong to another nation or individual.”

The museum also declined to talk to Tabachnik of the Denver Post over the year that he spent writing his series on Bunker and art smuggling. “There was no conversation. They never spoke to me. They never gave me an interview,” he said. Nor would members of the Denver Art Museum board talk to Tabachnik.

The Cambodian government is also seeking a greater level of transparency from the Denver Art Museum, noted Bradley J. Gordon, a lawyer for the Kingdom of Cambodia. Speaking by phone from that country, he said that his client is eager to know about any other objects that left Cambodia and passed under Bunker’s eye. Gordon says Bunker helped make the DAM “a laundromat for looted objects,” which then passed into museums and private collections.

“For us, the disappointing situation at the moment is that Denver has still not handed over any provenance documents,” he said. “For our research, it’s important to have as many documents as we can.”

“Any sort of documentation that they have relating to Cambodian artifacts is helpful to us. But they’ve been silent,” Gordon noted. “We’re not getting any information from them at all.”

The museum countered in a statement that it has worked directly with the US Justice Department: “The museum has done so, including providing all records to the DOJ regarding the returned pieces.”

For the Cambodians, that’s not enough. “The DAM had stolen antiquities, and now they’ve been returned. They should be assisting us to better understand how those stolen antiquities got to the museum,” said Gordon, “The story’s not over yet. They have the opportunity to do the right thing now.”