Cambodian farmers near the temple complex at Koh Ker knew that if they saw sculpted feet on a temple floor, it meant that looters had sawn off a statue at the ankles before shipping it abroad. Emma C. Bunker, a researcher with close ties to the trade, also knew that. In 2013, Sotheby’s repatriated a tenth-century footless statue that she advised them to auction. Most objects that she opined on sold without a problem.

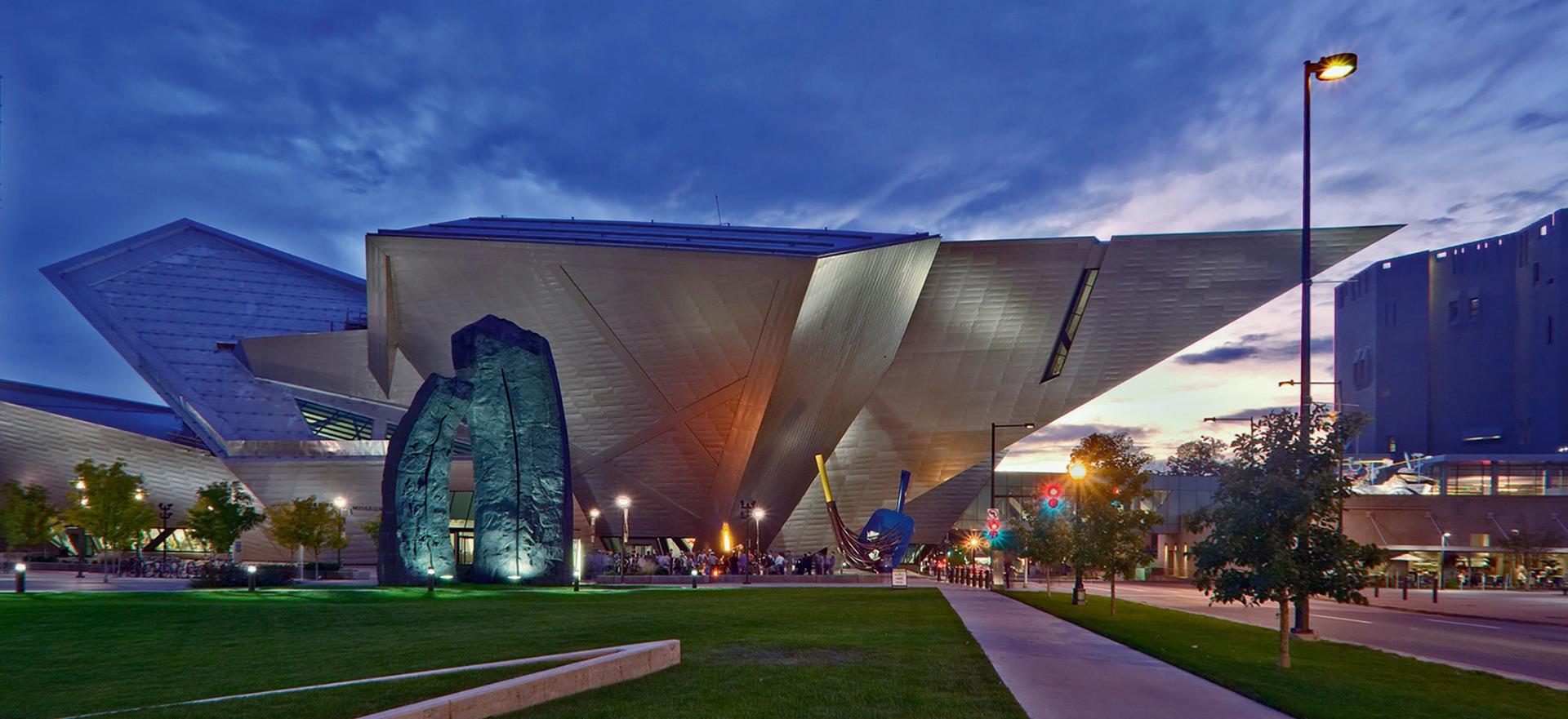

Last August the Denver Art Museum (DAM), under pressure from the US government, returned four statues that were shown to have been looted from Cambodia. As many more works in its collection now come under suspicion, the role of Bunker, a donor and researcher who helped bring those objects to the museum, sheds new light on a notorious smuggling operation.

Those most recent revelations come from the Denver Post, which traced how the DAM became what Bradley Gordon, a lawyer representing Cambodia, called a “laundromat” for looted sculpture from Cambodia and Thailand. The involvement of Bunker, once a mostly-unnamed link, brings fresh scrutiny from law enforcement and embarrassment for the museum.

The DAM, a relatively small and modestly funded institution, was an improbable waystation in a network of dealers who bought sculptures illegally, shipped the works to Bangkok and beyond, and arranged museum exposure to enhance their value. Bunker often helped dealers falsify the works’ provenances, investigators say.

Douglas Latchford, who collaborated with Bunker, died before he could be tried on smuggling charges Tang Chhin Sothy/AFP via Getty Images

The museum’s Cambodian connection began with Douglas Latchford, the now-notorious English expatriate dealer who paid impoverished rural Cambodians to detach sections of in-situ sculptures for him to export and sell. Looters in his service told of payments that changed their lives. Latchford died in 2020 while under US indictment for fraud, smuggling and other crimes.

Bogus provenances

Latchford found a friend in Emma Bunker, who died in 2021, aged 90. Bunker wrote on Chinese and central Asian art, collaborating on three books with Latchford and travelling to sites in Cambodia and Thailand. Works in those books with bogus provenances brought high prices when Latchford sold them. Bunker was thanked publicly by trusting officials in Phnom Penh for her work on behalf of Cambodian culture. Researchers in Cambodian and Thailand now use the books to trace missing objects.

Latchford and Bunker’s provenances were also questioned by former looters who recalled pillaging sites as Khmer Rouge child soldiers and spoke of being paid by Latchford for objects.

Emma Cadwalader Bunker

Bunker’s emails, excerpted by reporter Sam Tabachnik of the Denver Post, mixed niceties toward “dear” Latchford with derision for curators and others who brought them unwanted attention and scrutiny.

Already in 1972, Bunker published an article tracking sculptures known as the Prakhon Chai bronzes to the Plai Bat II temple in north-east Thailand, probably with Latchford’s help. Not a single Prakhon Chai sculpture remains in Thailand, although Bunker’s writings helped boost their prices in the antiquities market. Thailand wants museums to return them.

Bunker was known to museum specialists and dealers, yet her name rarely surfaced beyond those groups. In the US government’s detailed forfeiture complaint of November 2021, issued when the DAM agreed to return the four looted statues to Cambodia, a person referred to only as “The Scholar”, is described as providing Latchford with cover and false provenances for looted sculptures.

“Over the years, the Scholar assisted Latchford on many occasions by verifying or vouching for the proffered provenance of Khmer antiquities that Latchford was trying to sell,” the complaint reads. “The Scholar” has now been confirmed, by the Denver Post, as Bunker.

The Denver Art Museum last year returned four statues that had been looted from Cambodia, but only recently has the involvement of Emma Bunker in trafficking come to light Courtesy of Denver Art Museum

The DAM has now taken Bunker’s name off an annual acquisition fund. It remains on a gallery that recognised her family’s financial gift, although the museum’s board, on which she sat for five years, is scrutinising that. “The DAM continues to research every object related to Emma Bunker,” says spokesman Andy Tyler, especially some “50 gifted works that could be categorised as Asian antiquities”. He said donations in her name will support provenance research in Asian art.

Yet the museum will not open its records to Bradley Gordon, the lawyer representing Cambodia. “The more we understand how Emma and Douglas manipulated the historical record and created false provenances, the easier it is for us to complete our job,” he says from Phnom Penh. “We’re in a country where there are thousands of temples and pedestals—legs and arms around pedestals at multiple crime sites.”

Gordon estimates that 2,000 Khmer sculptures are in museums outside Cambodia, and 2,000 in private collections. “Emma,” he says, “was one of a hundred people who assisted Douglas over the years. There’s a lot more to write about and a lot more to figure out.”