Archaeologists working in southern Peru have uncovered a 1,200-year-old ritual complex, featuring a D-shaped temple standing on top of a monumental platform. Located at Pakaytambo, around 600km southeast of Lima, it was built by the Wari, a civilisation that controlled much of Peru from AD600 to AD1000, centuries before the rise of the Inca.

“Wari’s presence in this region of southern Peru has always been elusive,” says archaeologist David Reid of the University of Illinois at Chicago, who led the research. “The Wari empire left no written records, so even the extent of their political boundaries and activities are poorly defined. So when we first saw the platform enclosure in the shape of a ‘D’, the hallmark of Wari imperial temples, we were really excited.”

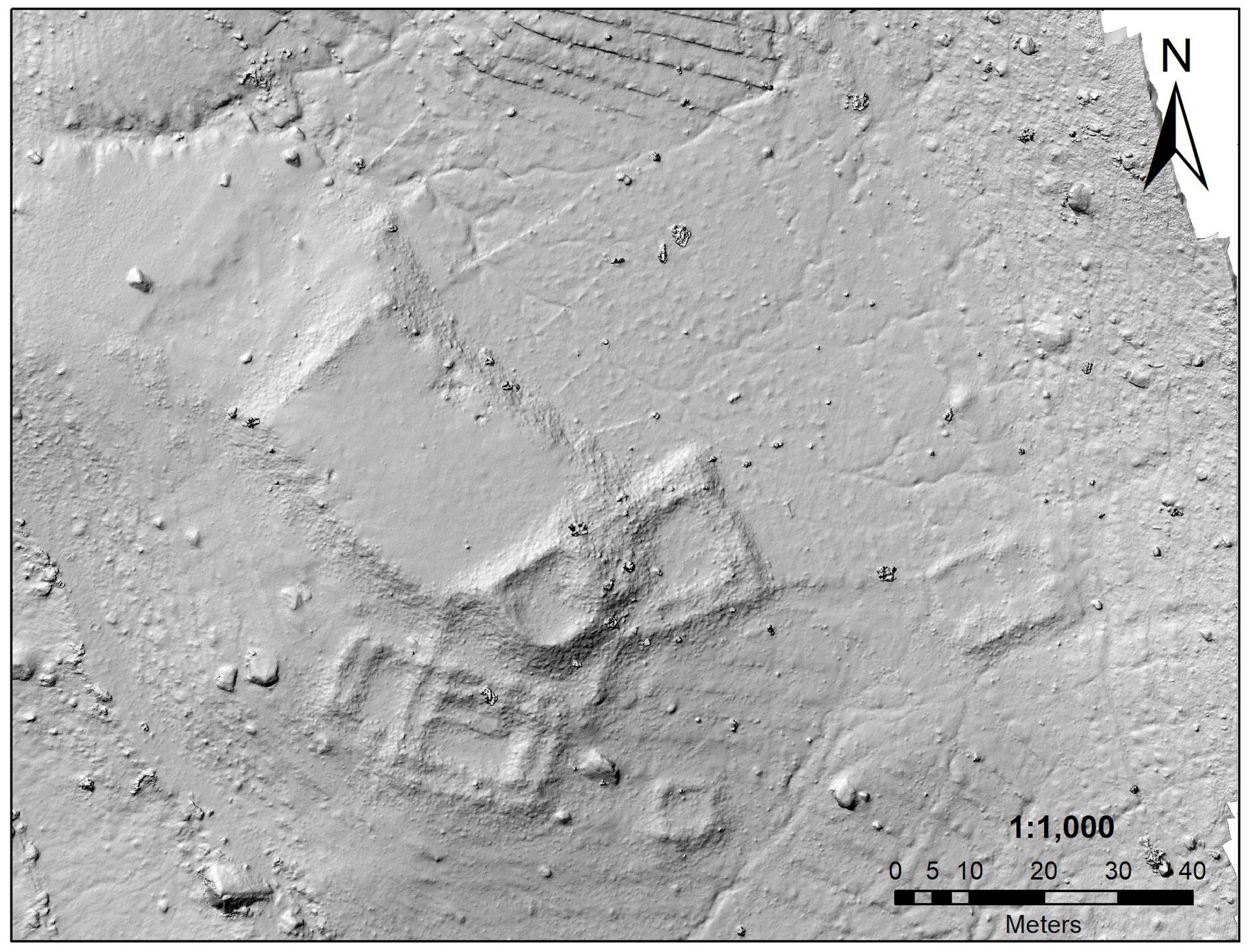

Reid identified the Wari ritual complex when researching Peru’s ancient road system with the aid of satellite imagery remote sensing. Afterwards, the site was studied through excavation, photogrammetry and with drones, leading to the creation of 3D models of the architectural remains.

3D model of site based on UAV drone imagery. Courtesy David Reid

This research revealed the presence of a monumental platform surmounted by a D-shaped temple, flanked on the slopes below by groups of buildings surrounding large, open spaces, referred to as patio groups by archaeologists. While excavating the patios’ halls and rooms, the team found evidence—including pieces of pottery, mammal bones, and oyster and mussel shells—that temple officials and Wari state representatives used these areas for domestic purposes.

“The excavations at the site confirmed the relation to the Wari state with decorated Wari pottery and radiocarbon dates that show it was founded at the apex of the Wari empire,” Reid says.

The complex was constructed after AD770 and abandoned by the end of the 10th century, an event marked by feasting and smashed vessels. Today, much of the temple is covered in ash from a volcanic eruption in 1600, according to Reid’s research paper, published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

Reid’s study suggests that Pakaytambo’s complex was a place where local communities gathered to attend Wari-sponsored ritual ceremonies and processions. The site’s plazas and courtyards, lower in the complex than the temple, were large enough to let hundreds of people attend the events. But the crowd couldn’t see what was happening above them, and access to the top of the monumental platform was probably restricted.

Archaeological excavation in the D-shaped temple. Courtesy David Reid

Pakaytambo can now be added to the more than 30 known Wari D-shaped temple complexes spread across the coastal and mountainous regions of Peru. They established these sites as their empire expanded, perhaps to create shared beliefs and religious practices among people of different linguistic and ethnic groups. In turn, this would have helped the Wari to maintain their political authority across the empire—a distance of roughly 1,500km from north to south. Located between the coast and the mountains, Pakaytambo may also have helped the Wari to control important trade routes and gain access to luxury goods and resources.

“When we consider how empires expand we often immediately think of direct force and militaristic expansion,” Reid says. “At the temple centre Pakaytambo, and other Wari ritual complexes recently identified in Peru, we also have growing evidence that the Wari incorporated people into the empire through shared religious beliefs and large-scale ceremonial events hosted by Wari elites.”

Future research will help to more closely determine the length of time that the Wari used Pakaytambo, while much remains to be revealed about the rituals and ceremonies held there. “The temple itself has only been partially excavated,” Reid says, “so future investigations are necessary to fully understand what specific rituals and offerings may have occurred at Pakaytambo.”