Damien Hirst, Banksy, now Skepta. For some time, Sotheby’s has been inching into the primary market by selling works directly from artists’ studios. Now, the auction house is firming up those moves, launching a new primary market sales channel for artists and their galleries.

Artist’s Choice launches on 30 September as part of the Contemporary Curated auction in New York, with seven lots consigned fresh from the studio by artists including Alexandre Lenoir, Atsushi Kaga, Katherina Olschbaur and Kevin Beasley. Pre-sale estimates range from $15,000 to $120,000. In time, all major sales could potentially include primary market pieces.

So, will the new sales channel ruffle dealers’ feathers? After all, the primary market has been their preserve for centuries.

Noah Horowitz, Sotheby’s worldwide head of gallery and private dealer services who is the brains behind Artist’s Choice, thinks not. “Part of the spirit of thinking about this was to create a win-win for artists and their galleries, and ultimately Sotheby’s and our collecting audience,” he says. The seven works in the first sale have been “consigned directly by the artist and the gallery in concert with each other”—though Sotheby’s is not privy to how the profits are split.

Aimed at mid-sized galleries rather than the megas who regularly consign and play the auction market, Mothers Tankstation, Casey Kaplan and Jeffrey Deitch are among those on board for the first iteration.

One of the biggest criticisms of the secondary market—and auctions in particular—is that artists make very little to no money out of the resale of their work, which can sometimes be flipped for astronomical prices preternaturally early.

According to Horowitz, at a commercial level, the new venture “empowers artists who have started to see a rising, burgeoning secondary market around their work to capture the upside that auction can uniquely provide”. He adds: “Gallery pricing is fixed, whereas, through the bidding process, we may be able to exceed that. Passing that power back to the consigners is certainly something that I think will be attractive to artists and galleries.”

On the contrary, where an artist may not be so visibly commercially successful, primary market prices can sometimes far exceed auction prices. In such instances, Horowitz notes how newer buyers are “increasingly looking to auction records to help justify what they’re spending in the primary market”. Artist’s Choice aims to provide a degree of price parity. “If it works well, it can help create a more steady market for the artists in a more holistic way,” he says, suggesting that dealers with months- or even years-long waiting lists for certain artists may then direct collectors to buy at auction instead.

Horowitz also notes how the new venture allows artists to control their markets to the extent they determine which works come to the block. “There are many artists and galleries out there who have had a fair amount of works come through the auction system that they’re not always 100% satisfied with,” he says. “Forget about the circumstances of how they got there. They’re not always satisfied with the quality of the work, or what part of their career a work represented. So this model says, 'If you want to take control of that, here’s a path for you to do so.'"

Aside from the commercial benefits, one of the most compelling aspects of the new initiative is that 15% of a work’s hammer price, jointly paid by the artists/galleries and Sotheby’s, goes to a charity or institution of the artist’s choosing. In recent years, galleries have cottoned onto the fact that donating to artists’ charities has helped woo them to their rosters.

As Horowitz puts it: “Very outwardly, artists nowadays are considerably more socially engaged with causes in varying shapes and forms than has ever been the case.”

In Sotheby’s case, however, the beneficiaries of its new channel are not limited to non-profits, though Horowitz says it would “be preferable if that were the case”.

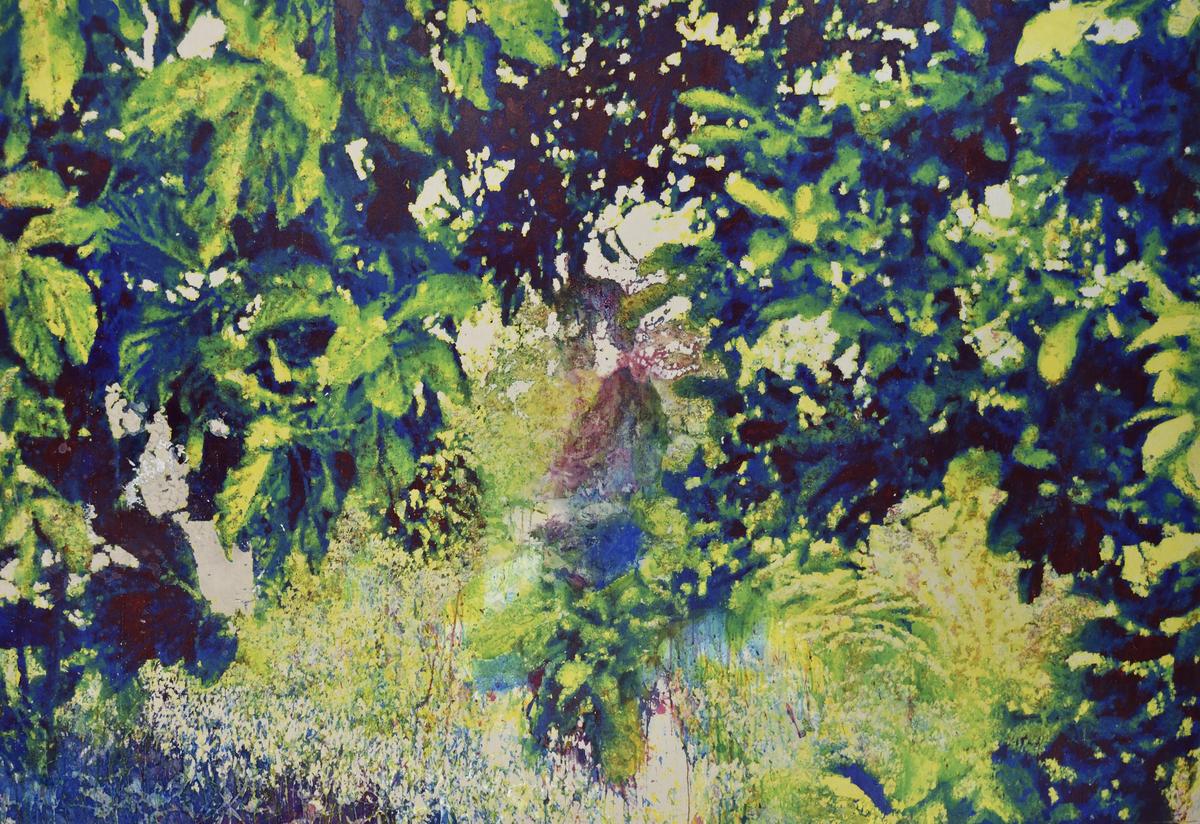

Todd Gray's Atlantic (New Futures).

Courtesy the artist and David Lewis. Photo: Silvi Naçi

One of the beneficiaries of the first sale is the forthcoming Sedabuda School in Ghana, which the artist Todd Gray founded with his wife Kyungmi Shin. Gray first traveled to the West African country in 1992, when he went as a commercial photographer to shoot Stevie Wonder’s album cover. Using the money from a grant, he found a three-acre plot by a fishing village and began building an adobe home with 15 villagers in 2006. Today it’s a secluded residency; “a place to read, think and be in the rhythm of nature”, Gray told Musée Magazine. Construction on the school began in 2017 and remains ongoing. Gray and David Lewis Gallery are consigning the print work, Atlantic (New Futures), which is expected to fetch $30,000-$40,000.

Meanwhile, Keven Beasely, who is consigning the mixed-media work, The Red Banana Tree (Forstall) (est $40,000-$60,000), is donating his 15% to the L9 Center for the Arts, which was founded by the New Orleans-based photographers Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick in 2007.

More recently, Beasely founded his own initiative in the Louisiana city. Instead of producing an art work for the Prospect New Orleans biennial in 2021, he bought a plot of land in the Lower Ninth district of New Orleans which had laid vacant and overgrown since Hurricane Katrina in 2005, clearing it and planting a garden. For now, Beasely says in a New York Times article, the garden is “a resource that will provide free internet, a place to relax, and in time, vegetables from the raised planters and fruit from the citrus trees”.

As well as charitable endeavours, artists will also be able to pledge their 15% towards one of their own future projects. As Horowitz puts it: “Artists and galleries have a lot of costs regarding commissions and participation in biennials and exhibitions. Artist's Choice can be a means to help raise money against those projects.”

As the former director of Art Basel in the Americas, Horowitz recounts the numerous conversations he has had with dealers over the years about the pressures they face, especially smaller and midsize galleries. "It might be funding catalogues for an exhibition, or the production of works that they have to either pay out of pocket or go to patrons of their gallery to fundraise, in which case there can be promises against future work. It’s how the system works, but it can get complicated.”

The new venture aims to ease some of those burdens. “Fundamentally it’s about trying to identify ways to support artists and their galleries,” Horowitz says.