I have long puzzled over why Van Gogh’s paintings of his own chair and that of Gauguin were separated. They are so obviously a pair and Vincent must have expected them to hang together, facing each other.

Van Gogh’s Chair (November 1888-January 1889) was sold by Vincent’s sister-in-law Jo Bonger to the National Gallery in London in 1924. Gauguin’s Chair (November 1888) remained with the family, ending up at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum on its establishment in 1973.

Splitting up the pair seems most unfortunate. It also struck me as surprising that Bonger had sold off her brother-in-law’s own “chair”, rather than that of Gauguin, who was just a friend.

An answer comes in an article by Louis van Tilborgh, a senior researcher at the Van Gogh Museum, in the latest issue of Simiolus, the quarterly journal of Dutch art history. In “Van Gogh, Gauguin and Rembrandt” he argues that Bonger took a dislike to Gauguin—and wanted the painting of his chair hidden away.

This interpretation helps us see the two chair paintings in a fresh light. In his article, Van Tilborgh rejects some of the traditional interpretations of the pictures, focussing on Van Gogh’s artistic ambitions and his partnership with Gauguin.

The collaboration of the two artists—which had started off with such high hopes, but ended in tragedy—is illustrated by these two paintings. The men presumably both had their favourite chairs in the Yellow House, where they lived together in Arles for two months in the autumn of 1888.

Vincent’s own chair was a simple piece of rustic furniture with a straw-covered seat, reflecting something of his more austere personality. Gauguin had a comfortable armchair, depicted under gaslight, with a candle and two novels, suggesting a sophisticated man who enjoyed the evening hours. In a sense, the two pictures can be regarded as “portraits” of the artists.

Van Gogh began the paintings in mid-November 1888, when relations between them were still friendly. He finished Gauguin’s Chair and most of Van Gogh’s Chair within a few days. A month later their collaboration came to a terrible end, when during the evening of 23 December 1888 Vincent mutilated his ear. By this time serious tensions had developed between them. Gauguin quickly fled to Paris.

In January Van Gogh returned to the picture of his own chair, adding the pipe and tobacco on what had been an empty seat. Smoking, for him, represented consolation and relaxation, which was now much needed. He also included onions in the background, which presumably had a meaning for him, although their symbolism remains somewhat obscure. Finally, he prominently signed the picture, indicating that it was both his work and a representation of his personal seat.

Traditionally, art historians have regarded the two paintings as “empty chairs”—and have linked them with the tensions that the artists were facing. But Van Tilborgh points out that in mid-November, when they were mostly done, relations were still collaborative. And when fully completed, he sees both chairs as not empty, but “occupied” and speaking of “presence”—one with Gauguin’s books and the other with Van Gogh’s pipe.

Vincent sent the two paintings to his brother Theo in Paris in April 1889. After Vincent’s suicide in July 1890 ownership passed to Theo and following Theo’s death in January 1891 to Bonger.

The public’s first opportunity to see Van Gogh’s Chair came in 1905, when Bonger lent it to a major retrospective of the artist’s work in Amsterdam. Comprising nearly 500 works, it is still the largest Van Gogh show ever held. Although most of the important family paintings were lent, Gauguin’s Chair was not included.

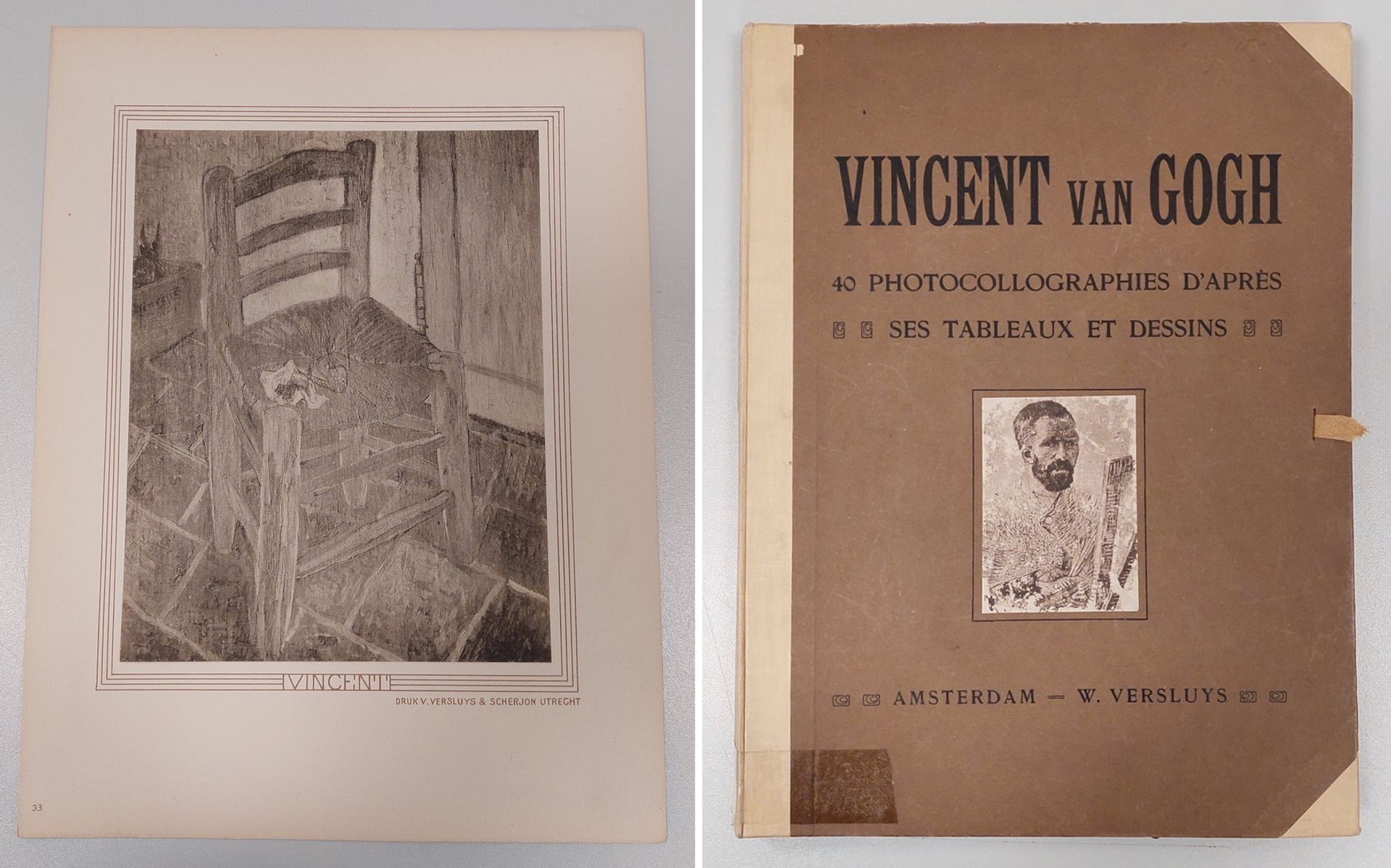

Reproduction of Van Gogh’s Chair and cover of Vincent van Gogh: 40 Photocollographies d’après ses Tableaux et Dessins, Amsterdam (1905) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Van Gogh’s Chair (but not Gauguin’s Chair) was also included in an important portfolio of reproductions of the artist’s work which was published in 1905. From then onwards Van Gogh’s Chair was lent to ten other exhibitions up until the First World War, which meant it came to be regarded as a key work.

In December 1923, Bonger loaned Van Gogh’s Chair to the artist’s first one-man show in London, at the Leicester Galleries. A few weeks later it was bought by the National Gallery for just under £800, with funds provided by Samuel Courtauld.

But it was not until 1928 that Gauguin’s Chair was first publicly exhibited. This was three years after Bonger’s death, when the collection was managed by her son, Vincent Willem.

Van Tilborgh believes that Bonger resented Gauguin because after his friend’s suicide he had tried to claim credit for Van Gogh’s artistic innovations. One can also speculate she partly blamed Gauguin for Van Gogh’s tragic self-mutilation.

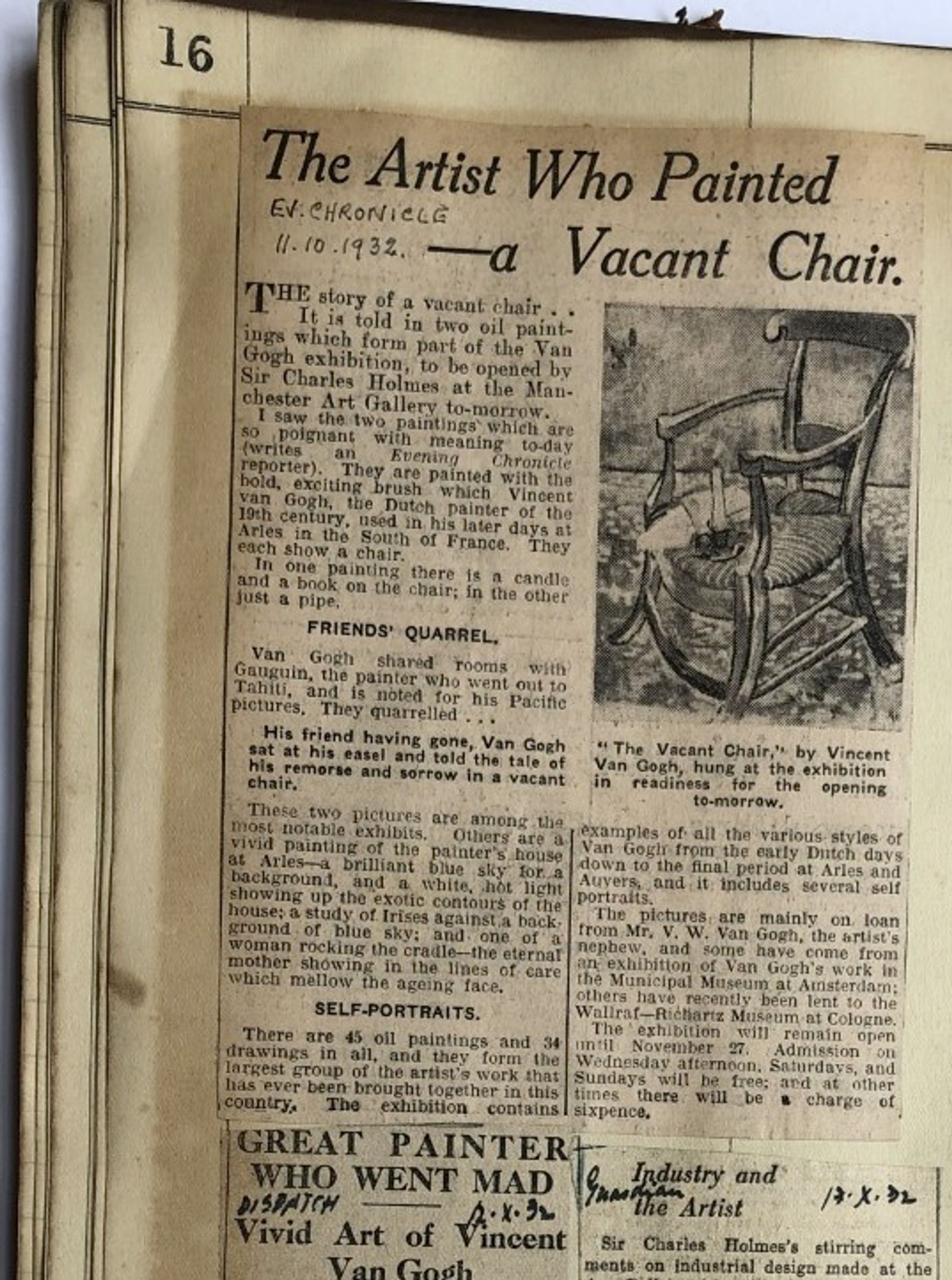

The first time the two chair paintings were brought together was at a Van Gogh show at Manchester Art Gallery in 1932. A newspaper article noted that the pair were “among the most notable exhibits” and were “poignant with meaning”, an indication that their importance was finally being recognised.

Manchester Evening Chronicle, 11 October 1932, with an article on the city’s Van Gogh exhibition (a cutting in an album at Manchester Art Gallery) Credit: Manchester Art Gallery

These two still lifes reveal much about one of the most important collaborations in art history. Sadly, the paintings are now only rarely brought together.

Other Van Gogh news:

Now that the Hermitage Amsterdam has cut its links with the St Petersburg museum, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it has struck off on its own—with Van Gogh. This is part of a fundamental rebranding, with the “Hermitage” dropping a “m” to become “Heritage”, with a focus on Dutch heritage.

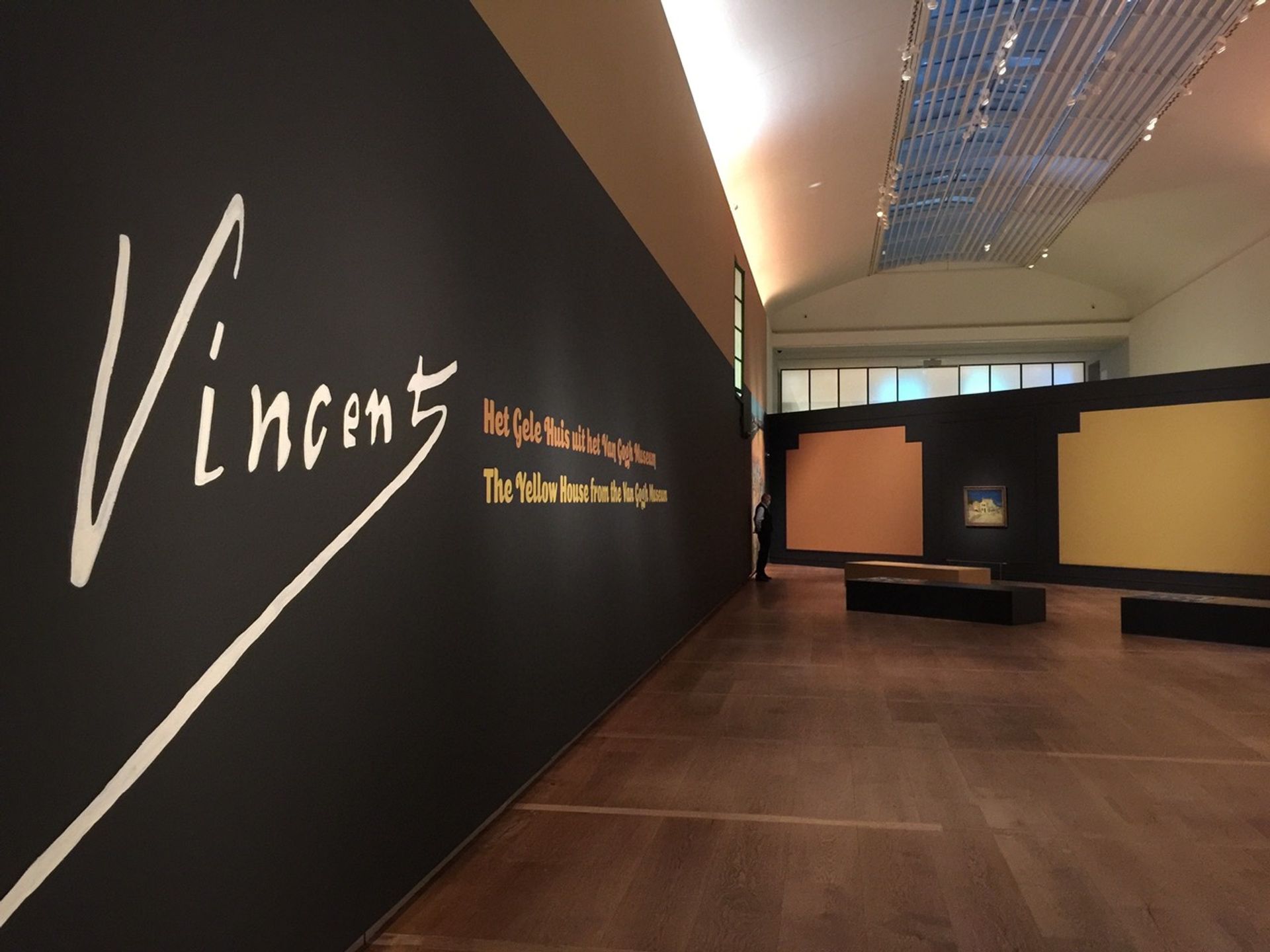

Van Gogh’s The Yellow House (September 1888), at the far end of the room, in the rebranded “Dutch Heritage Amsterdam” Credit: The Art Newspaper

The Van Gogh Museum has offered an extremely generous loan, The Yellow House (September 1888). This single painting is displayed alone, at the far end of a huge gallery. In side rooms, there are displays of reproductions of Van Gogh's art and panels about his life, presented engagingly. With only a single original picture, even though a masterpiece, and a €15 ticket charge it is hardly attracting the crowds that flock to the nearby Van Gogh Museum. But supporting Heritage Amsterdam, which has taken decisive action over Ukraine, is a worthy cause.

Van Gogh is certainly in good company at Heritage Amsterdam. After The Yellow House returns home to the Van Gogh Museum it will be followed by Rembrandt’s last Self-portrait (1669) from the Mauritshuis in The Hague (28 June-24 July).

Martin Bailey is the author of Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Frances Lincoln, 2021, available in the UK and US). He is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019).

Martin Bailey’s recent Van Gogh books

Bailey has written a number of other bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: the Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence(Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US) and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US). Bailey's Living with Vincent van Gogh: the Homes and Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh has been reissued (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

• To contact Martin Bailey, please email: vangogh@theartnewspaper.com. Please note that he does not undertake authentications.

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.