“The most beautiful paintings are those one dreams of while smoking a pipe in one’s bed,” Vincent van Gogh wrote from the Yellow House in Arles. In the letter to his friend Emile Bernard in June 1888, he added that it was impossible to create pictures which were quite so beautiful as the perfections of “nature’s glorious splendours”—but nevertheless one should try.

A few months later Vincent wrote again to Bernard: "In order to do good work you have to eat well, be well housed, have a screw from time to time, smoke your pipe and drink your coffee in peace.“

Although most aspects of Van Gogh’s life have been endlessly explored since his death, the role of his pipe has received relatively scant attention. But smoking, for Vincent, was vital, since he regarded it as a source of consolation when tackling the endless challenges he faced (for health reasons we obviously do not suggest that readers emulate his example).

In one of Vincent’s earliest preserved letters, when he was 19, he wrote to his younger brother: “Theo, I must again recommend that you start smoking a pipe. It does you a lot of good when you’re out of spirits.” Two years later, in 1875, he described his pipe as “an old, trusty friend, and I imagine we’ll never part again”.

In a little-known reminiscence, a retired tailor from the Van Gogh family’s village of Helvoirt once remembered cleaning Vincent’s clothes during a Christmas visit. “The suit stank of smoke and was completely unpresentable”, 70-year-old Frederick van de Plas told a Dutch writer in the 1920s.

While working as a teacher in Isleworth, west London, aged 23, his landlady Annie Slade-Jones complained about the smell of his smoking. He therefore gave her scented violets: “I bought some for Mrs Jones to make up for the pipe I smoke here now and then, mostly late in the evening in the playground. The tobacco here is rather strong.”

Van Gogh was by then addicted to smoking. Although failing to sell his work, on one occasion in 1884 he apparently gave a painting to the Eindhoven tobacconist Jansje van den Broek to settle a bill. This picture, Watermill at Gennep, was bought by Baroness Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza at Sotheby’s in 1996—for £552,000.

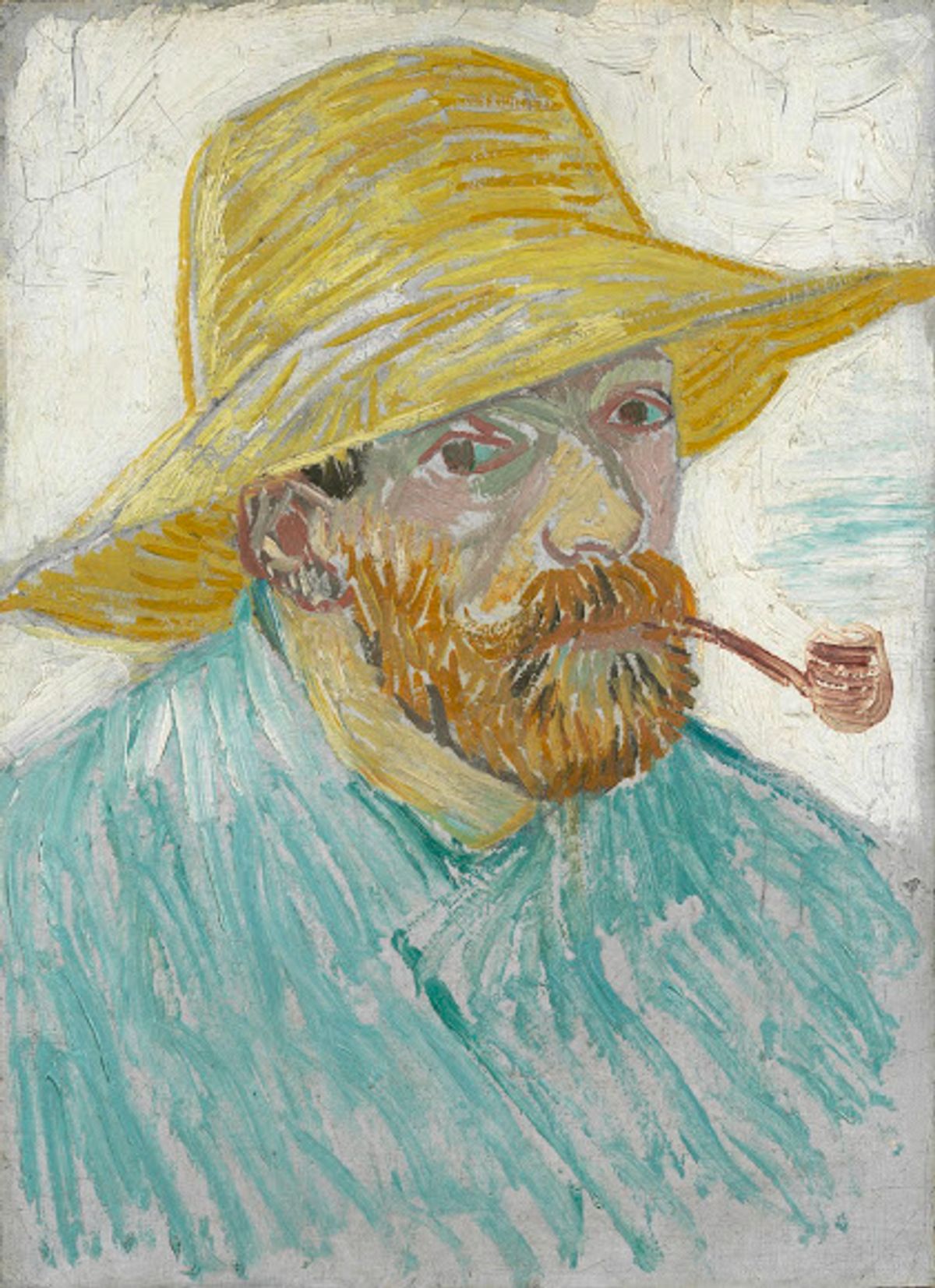

Vincent van Gogh’s watercolour of Still Life with Vase, Honesty, Pipe and Tobacco (1885) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

After Vincent’s father Theodorus died of a stroke in 1885 he painted a memorial still life which included the deceased’s pipe and tobacco pouch. Van Gogh later reused the canvas, to save money, but a watercolour sketch survives.

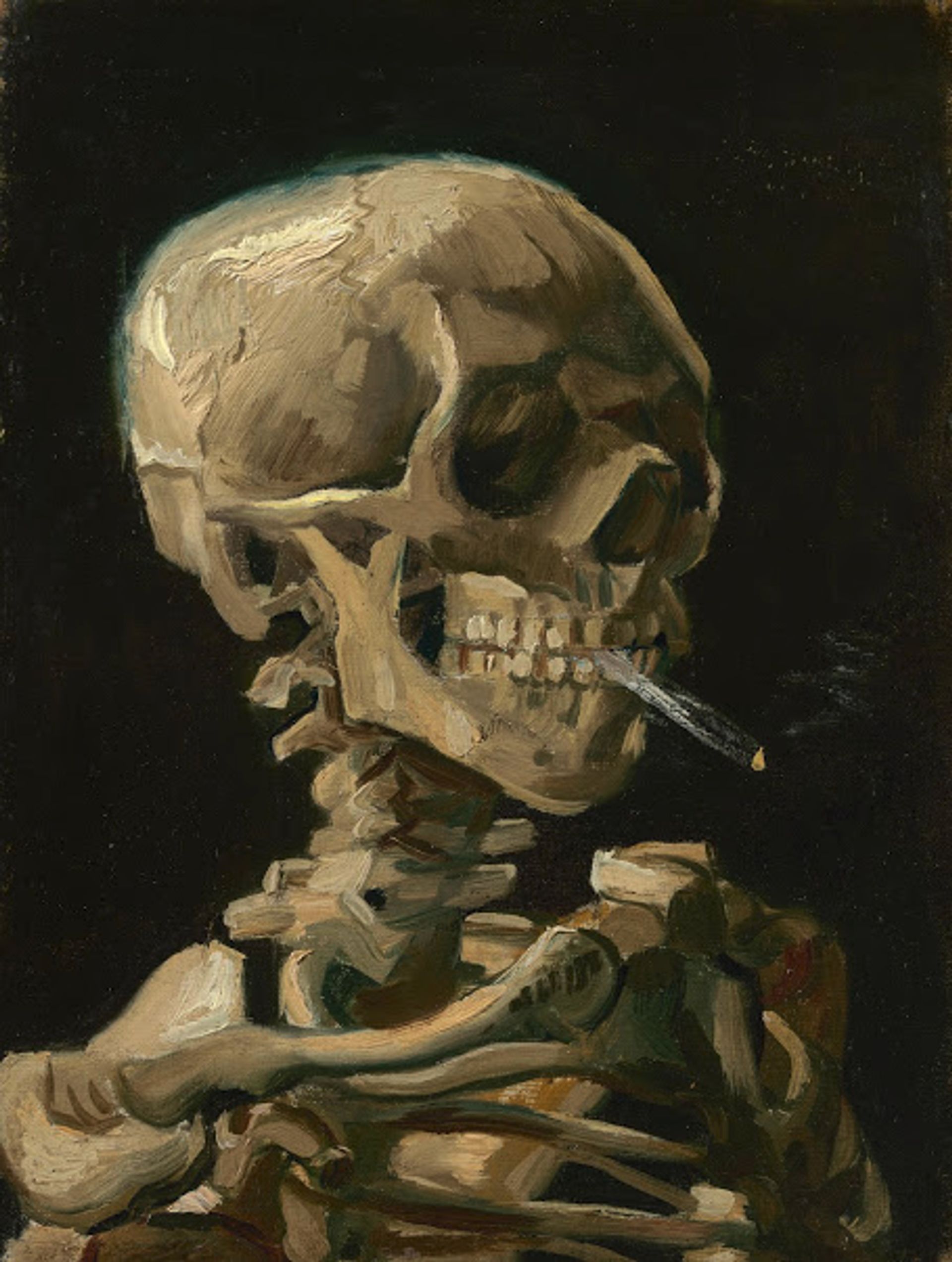

A few months later, in Antwerp, Van Gogh painted Head of a Skeleton with burning Cigarette (1886). Then briefly studying at the art academy, the picture was presumably something of a studio prank. Nowadays we can hardly look at this painting without seeing a warning about cancer. But for Van Gogh, it was just the opposite: for him a lighted cigarette would have represented life, not death.

Vincent van Gogh’s Head of a Skeleton with burning Cigarette (1886) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Tobacco always represented a drain on Van Gogh’s precarious finances. When Paul Gauguin joined Van Gogh in the Yellow House he was shocked to see how money was being frittered away. Gauguin therefore divided their funds: “So much for nocturnal excursions of a hygienic sort [fortnightly visits to the brothel], so much for tobacco…“

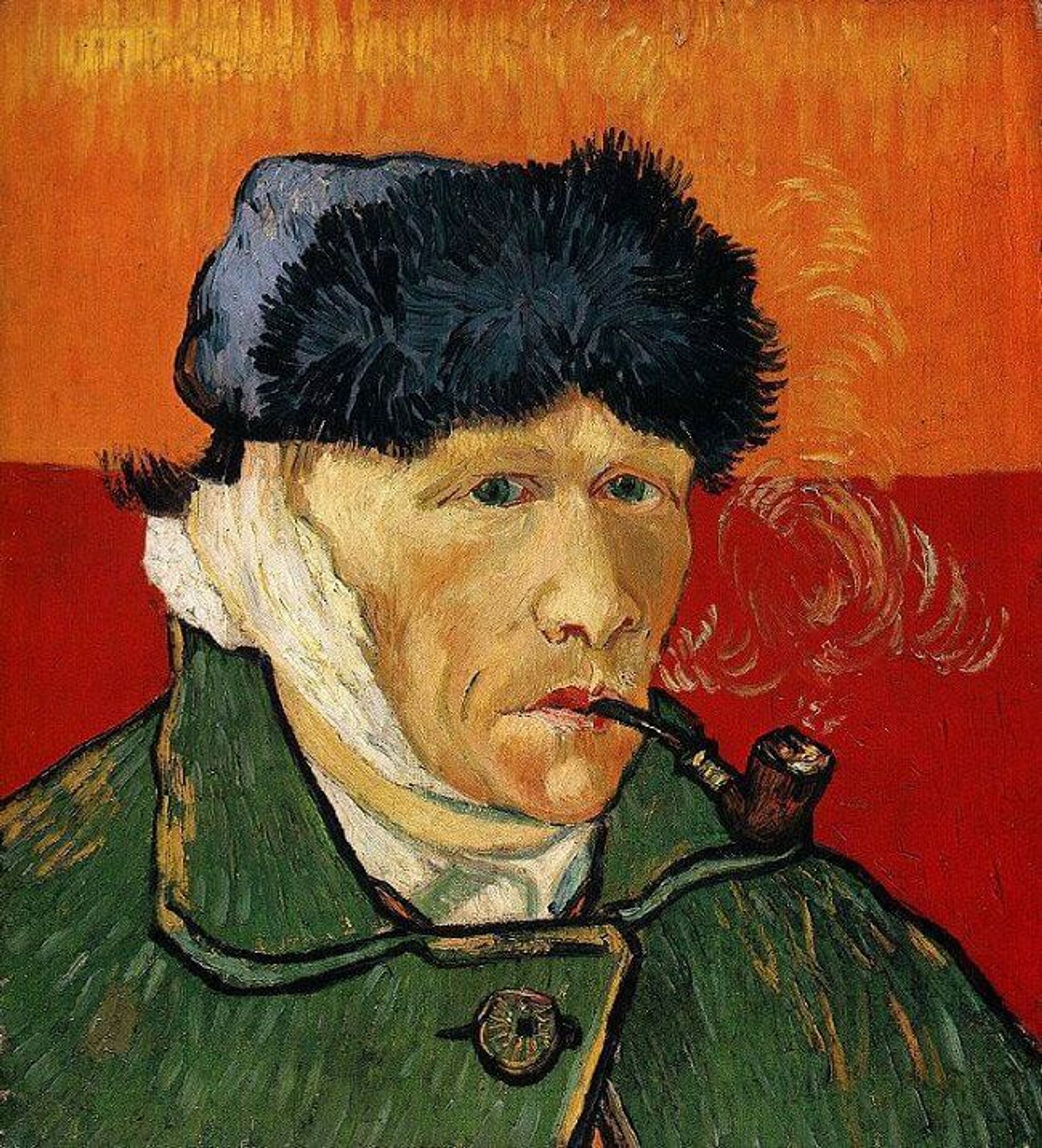

Vincent van Gogh’s Self-portrait with bandaged Ear and Pipe (1889) Credit: private collection

Just before Christmas in 1888 came the mutilation of the ear, the incident which led to Gauguin fleeing back to Paris. Fortunately Van Gogh’s wound quickly healed. In the spring he wrote, slightly lightheartedly, to his sister Wil: “Every day I take the remedy that the incomparable Dickens prescribes against suicide. It consists of a glass of wine, a piece of bread and cheese and a pipe of tobacco.”

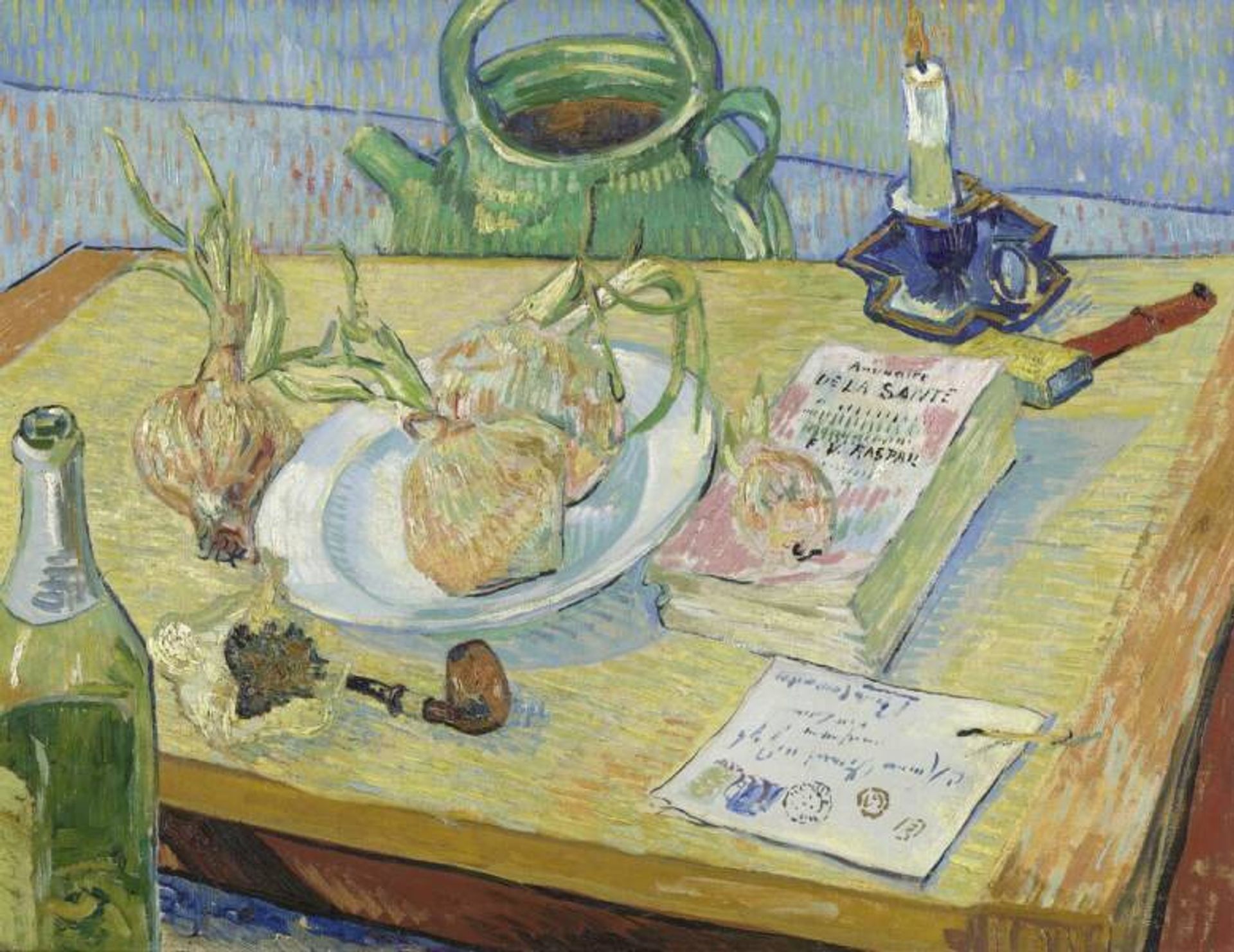

Although Dickens did not actually refer to suicide, in Nicholas Nickleby he suggested that melancholy could be cured: “Smoke a large pipe and drink a full bottle”. A month after mutilating his ear Van Gogh portrayed both objects in a very personal still life, alongside a medical manual by François Raspail and a letter from Theo (although the bottle has been opened and may not be full).

Vincent van Gogh’s Still Life (1889) Courtesy of Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Right up to the end of Van Gogh’s life he felt that his pipe had a calming effect, but it failed to save him from his ultimate fate. After wounding himself from a revolver shot on 27 July 1890, he staggered back to his garret bedroom in the small inn. When Dr Paul Gachet arrived, Van Gogh asked for his pipe, which was in still in his waistcoat pocket. Vincent began to smoke in silence. A day later he was dead.

Just over a year earlier Van Gogh had painted what can now be seen as his own memorial, a picture of his empty chair, now at the National Gallery in London. On the straw seat, recalling an absent sitter, lies his trusty pipe and packet of tobacco. This vignette represents a highly personal still life in a painting which is itself a symbolic self-portrait.

Vincent van Gogh’s Van Gogh’s Chair (1888-89) Courtesy of the National Gallery, London