On 19 November 1888, Vincent wrote to his brother Theo about his two latest pictures, describing them as “rather funny”. One was of his own empty chair in daylight, “a wooden and straw chair all yellow on red tiles against a wall”. The other was of Gauguin’s armchair. From what we know of Van Gogh’s character, by “funny” he probably meant curious, rather than amusing.

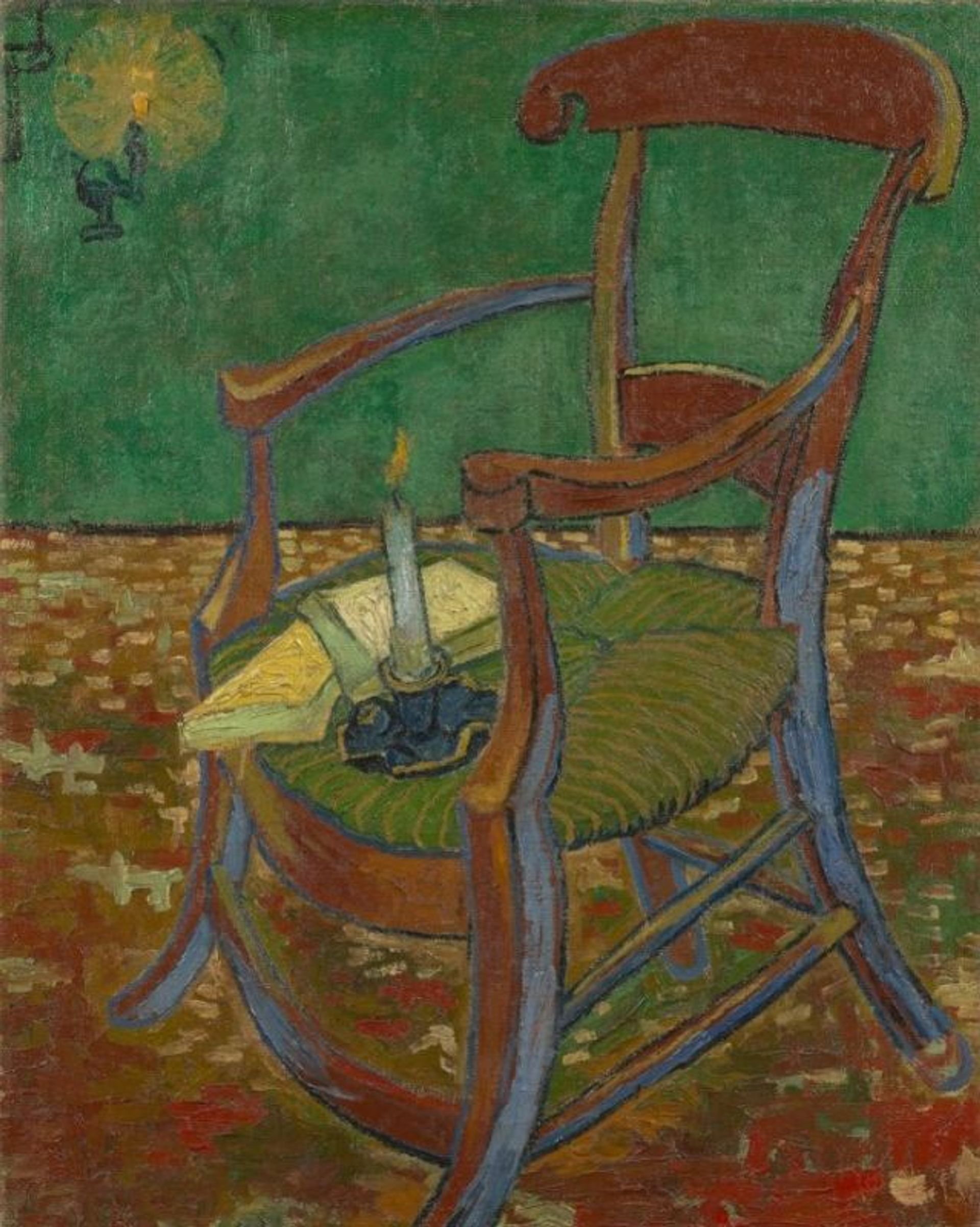

Vincent van Gogh, Gauguin’s Chair (1888) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The two chair paintings are his greatest and most innovative still lifes, after the Sunflowers. But for Van Gogh, empty chairs represented the person who would sit in them, so in a sense, they are equally portraits—telling us about the two artists who shared nine weeks together in the Yellow House in Arles.

The chairs would have stood in the front sitting room, where Van Gogh and Gauguin gathered in the evenings after a long day at their easels. It was there that they would talk, and often argue, about the future of modern art.

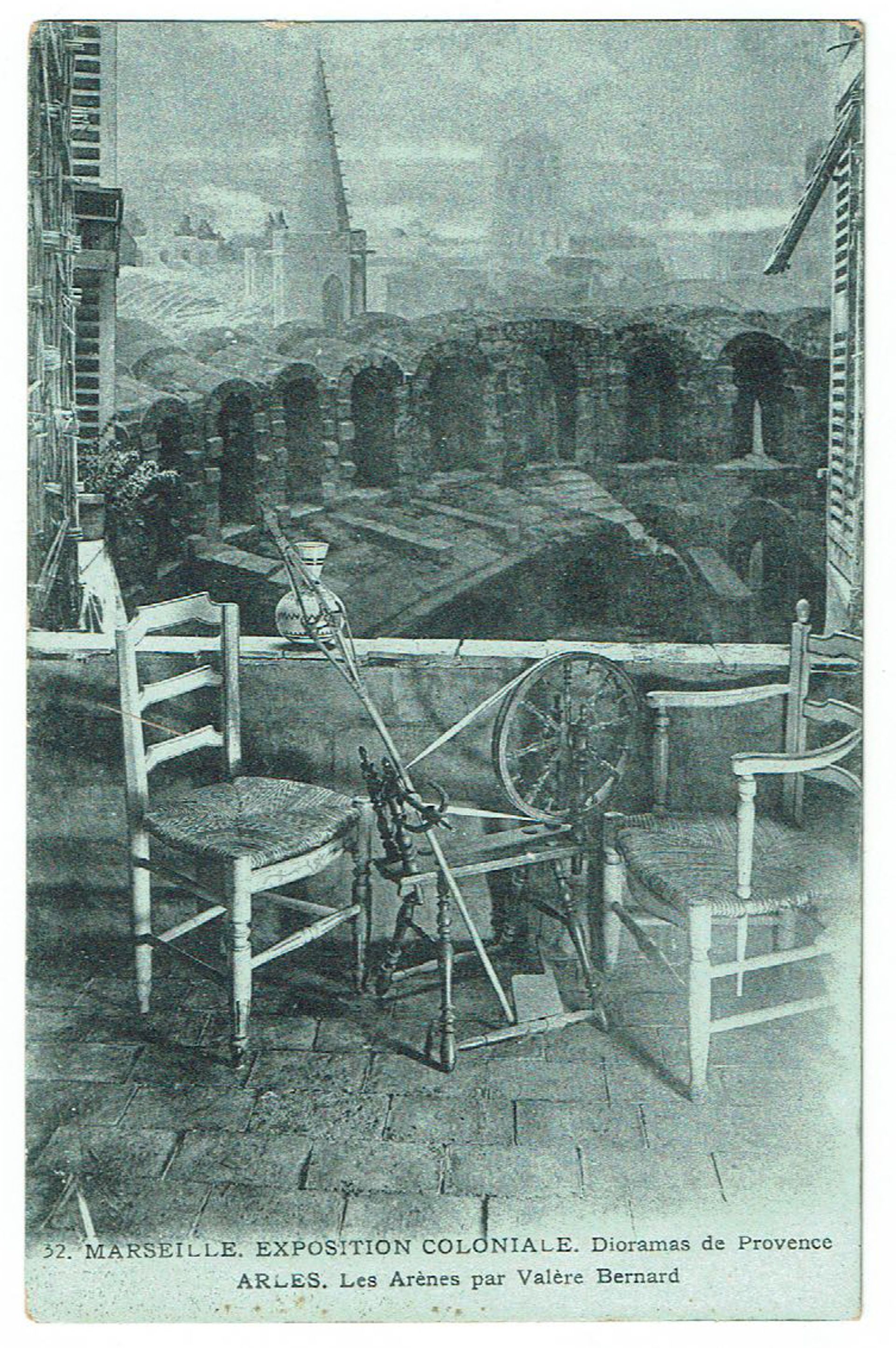

As furniture, the chairs were quite unremarkable: a 1906 postcard illustrates two very similar chairs, presented in a diorama to represent an archetypal Arles setting. But Van Gogh’s brush has transformed these mundane objects into highly imaginative visions.

Diorama of Arles, displayed at the Exposition Coloniale, Marseille (1906), postcard

Van Gogh’s Chair with its straw-covered seat is a simple, rustic piece of furniture, reflecting how the artist saw himself, as a modest man. The objects on the seat are very personal, suggestive of Van Gogh’s reflective personality: his pipe and tobacco pouch. Smoking was his constant pleasure, helping him to relax. The picture can therefore almost be seen as a self-portrait. The significance of the curious, signed box at the back, apparently filled with sprouting onions, remains an enigma.

The perspective of the composition is striking, with the chair almost thrusting into the viewer’s space. Although the walls of the interior were actually whitewashed, Van Gogh has painted them as light turquoise, to contrast with the yellow chair. The door probably leads outside, to the street and a small public garden.

Gauguin’s Chair is a night-time scene, perhaps a reflection of his renowned sexual prowess. The comfortable armchair represents a successful man at ease. On the seat is a glowing candle and two contemporary novels, suggesting that Gauguin would relax with a good book before going to bed.

The setting is illuminated by gaslight, which Van Gogh had had installed just a month earlier, partly as a further incentive to encourage Gauguin to make the journey south. This time the wall is a deep green.

A month after painting these domestic scenes, life at the Yellow House was shattered when Van Gogh mutilated his ear, with Gauguin fleeing back to Paris. This pair of still lifes remains as a testimony of their time together.

The two chairs were painted as a pair

One of the mysteries, which does not appear to have been addressed in the Van Gogh literature, is why the two paintings were split up: Van Gogh’s Chair is now at the National Gallery in London and Gauguin’s Chair is at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

On Vincent’s death in 1890 both pictures were inherited by his brother Theo, and after he died the following year they passed to Theo’s wife Jo Bonger and her son. In 1923 they lent Van Gogh’s Chair to an exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in London.

A few weeks later it was bought by the National Gallery for just under £800, with funds provided by Samuel Courtauld. In 1926, Courtauld suggested that Van Gogh’s Chair might be sold, in order to buy one of the artist’s landscapes, explaining that “we ought not to have too many Van Goghs”. Fortunately, A Wheatfield, with Cypresses (1889) ended up being acquired without the sale of the chair painting.

Considering that Theo’s wife Jo then owned around 200 paintings it is surprising that she chose to sell one which was quite so personal. It also meant splitting up what the artist very clearly regarded as a pair.

The two still lifes have proved a great inspiration to later artists. Lucian Freud loved them, once commenting to his biographer, William Feaver: “Everything is autobiographical and everything is a portrait, even if it is a chair.”