Botticelli’s ultima maniera (last manner) is a rather strange and archaic one. Many people, even specialists, dislike it and tend to ignore these works, more or less. However, I consider them to be a fascinating group for that very reason—highly idiosyncratic and beyond their time. Botticelli might have felt that a younger generation was about to surpass him and therefore went to extremes to define his own way. Those paintings have often been connected with the fanatical Dominican preacher Savonarola, but some scholars have become sceptical about this way of interpreting them. Rightly so, as the Florentine friar favoured paintings that were simple and naturalistic—almost exactly the opposite of what you can say about late Botticelli’s style.

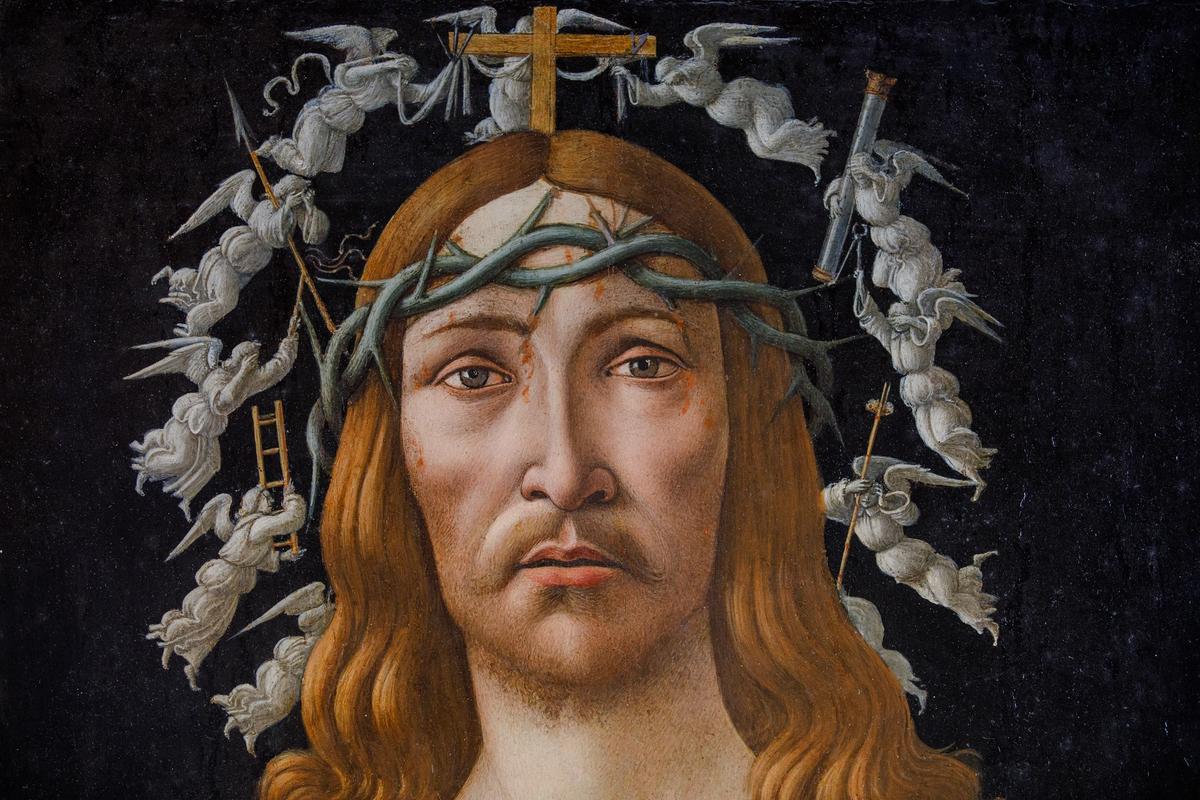

It was in 2009, on the recommendation of Keith Christiansen, that I first came across this both stunning and puzzling Man of Sorrows. At that time, the painting was included in the exhibition Botticelli: Likeness, Myth, Devotion at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt on which I collaborated. I had the pleasure to publish the picture for the first time in the catalogue (pp. 354–357, cat. 78) and to examine it closely during the exhibition. It was mentioned only marginally by Ronald Lightbown in his 1978 monograph, but in 1963 Federico Zeri had already attributed it to the master in a Sotheby’s expert’s report.

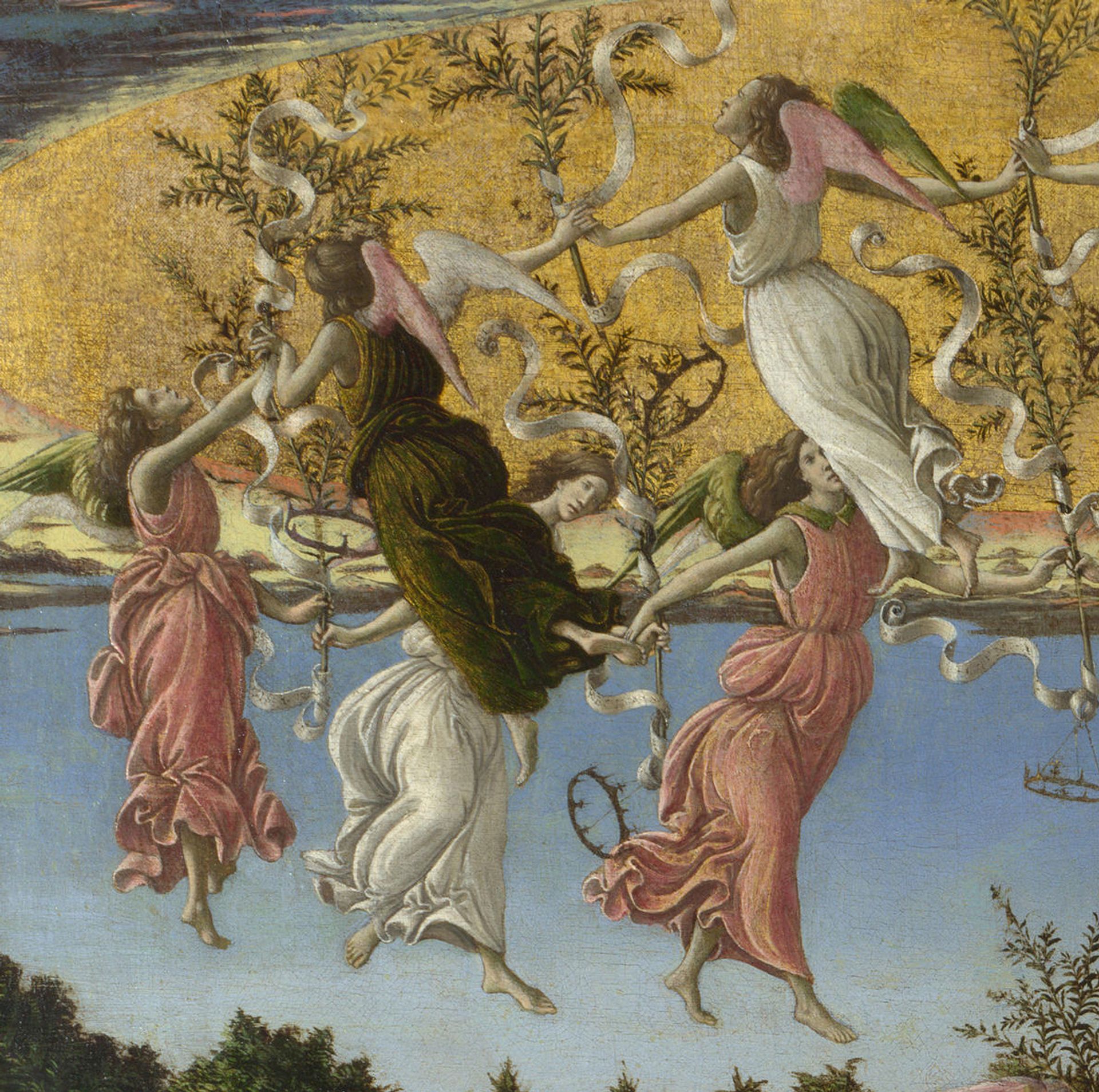

A detail from Botticelli's Mystical Nativity (1501)

Courtesy of The National Gallery

The use of subtle gradations of light and shade to model the face of Christ can indeed be compared with portraits by Botticelli, while the formation of the hands—including specific anatomical anomalies such as the bent little finger—is also typical of this painter’s late period. Botticelli used the crown, fashioned from a greenish-blue branch with long, sharp thorns, in an identical form in the Lamentation of Christ in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan.

Above all, however, we must direct our attention to the elongated figures of the angels. With their exalted movements and generously measured, billowing garments, and even in such details as their wings and feet, they are closely related to the circles of angels in the Coronation of the Virgin in the Uffizi and in the Mystical Nativity of 1501 in the National Gallery in London. In both quality and complexity, the painting surpasses other half-length depictions of Christ from the Botticelli workshop. That does, of course, not exclude some minor intervention by assistants as was common in several Botticelli paintings.

The uniqueness and “pictorial intelligence” of the iconographic invention—a feature unparalleled in Italian art—also speak in favour of the work’s attribution to Botticelli. The painter shows Christ as a strictly frontal half-length figure, yet he has subtly circumvented the symmetry, using a turn of the neck to shift the head toward the left. The eyes also evade precise conformity to the symmetrical design of the face. By placing the fingers of his left hand in a slit in the crimson fabric, which corresponds to the thrust of the lance, Christ calls attention to the wound, although it is actually concealed beneath his robe.

The halo formed by angels bearing the Arma Christi is a bold invention; set off in grisaille against the black background, these figures are identified as inhabitants of a different realm. With fluttering robes, they encircle the head of the Redeemer in flight, adhering to an orbit that continues behind his hair.

In this painting, Botticelli combined several thematically interrelated pictorial types whose iconographic traditions occasionally overlap: a feature of the Man of Sorrows is the display of the scars; The Ecce Homo is alluded to by the crown of thorns, the purple robe, and Christ’s bonds; finally, it was the Vera Icon from which Botticelli adopted the strict frontality of the upright head.

This method of combination which operates on the levels of both form and content is as characteristic of Botticelli’s devotional pictures as the principle of “detemporalisation” which isolates motifs and their significance from their narrative contexts and condenses them into complex symbolic images. The latter merge theological indoctrination with the endeavor to spark the viewer’s emotions. Thus, the Man of Sorrows not only represents an important example of Botticelli’s late period, but also adds a striking facet to our understanding of the depiction of Christ in the Renaissance.

- Bastian Eclercy is the head of Italian, French and Spanish paintings before 1800 at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt and a specialist in Italian Renaissance and Baroque painting. He was one of the main contributors to the 2009/10 Städel exhibition catalogue, Botticelli: Likeness, Myth, Devotion, in which he published this painting. Eclercy has curated several exhibitions, for example Maniera: Pontormo, Bronzino and Medici Florence (2016).

- Read Frank Zöllner's accompanying comment here