The work of fine artists in the US and in much of the rest of the world is protected by law from being altered or destroyed without their permission. (In the US that law is called the Visual Artists Rights Act, or VARA, enacted in 1990.) Still, work may not be as protected as artists would like, at least in the US. Particularly for works of public art that are identified by their creators as “site-specific”, no law compels the owner to maintain a site just as it had been when the artist conceived their work.

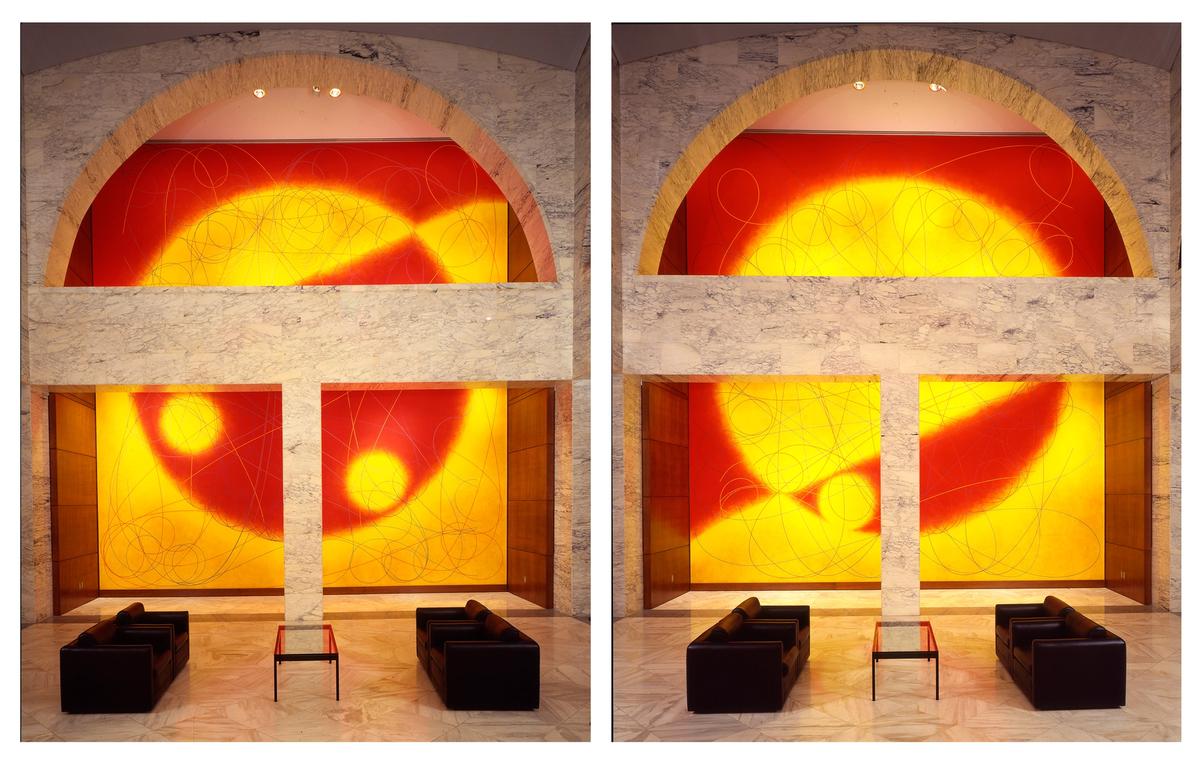

Just ask painter Dorothea Rockburne, whose frescoes in the landmark Philip Johnson-designed building at 550 Madison Avenue in Manhattan, each measuring 30ft by 29ft, will no longer be on view to the public. The lobby where the murals, Northern Sky and Southern Sky (both 1993), are located is undergoing a remodeling and the artwork will be placed in what will become a “private amenity club” available only to building tenants.

The frescoes were specific to the site, the 89-year-old-artist says, because she spent three years investigating the electromagnetic field at the building’s location. The artist, who earned a doctorate in mathematics in 2016 and views many of her paintings as solving visual equations, says she “would not move the murals to another location, because they wouldn’t be meaningful anywhere else”.

Not-so-specific definitions

The website of New York’s Museum of Modern Art defines site-specific as “a work of art designed for a particular location”, while the Guggenheim Museum website’s definition is a bit more expansive: “Site-specific or Environmental art refers to an artist’s intervention in a specific locale, creating a work that is integrated with its surroundings and that explores its relationship to the topography of its locale, whether indoors or out, urban, desert, marine or otherwise.”

Whatever the definition, site-specific art is designed to be in a specific place, unlike framed paintings or tabletop sculptures that are considered “portable”. Site-specific works are often so large, complex or heavy that moving them is not only disruptive but also prohibitively difficult.

One such work is the nearly 500-ton site-specific rock and water installation Marabar (1984), which sculptor Elyn Zimmerman, 76, designed for the plaza and entrance to the Washington, DC headquarters of the National Geographic Society. By 2019 the installation was found to be an impediment when the society decided to build a new entrance pavilion. The installation, consisting of a 60ft-long and 6ft-wide reflecting pool bounded by five granite boulders and four other boulders in the surrounding landscape, was slated to be removed. But following criticism from museum officials, artists and architects, the society agreed to pay to relocate the work. It will be placed this summer near an arts centre at nearby American University, although the piece will change in the move. Instead of the pool being rectangular, it will be crescent-shaped; trees will now surround the piece and its title, which recalled a cave in E.M. Forster’s novel A Passage to India, will be changed based on the artist’s response to the new location.

Elyn Zimmerman's Marabar (1984), which will be removed from the headquarters of the National Geographic Society in Washington, DC © Elyn Zimmerman, courtesy of the Cultural Landscape Foundation

The installation “will be different, not less meaningful, but it will have a different meaning”, Zimmerman says, “based on its new location and how it interacts with the local community”.

She adds: “You can’t say that nothing can ever be changed.” Still, some artists try.

Out of site

Owen Morrel, a 71-year-old artist who claims that “all my work is site-specific”, writes into commissioning agreements that “the owners of the piece protect the copyright of the artwork by protecting the site”. Usually whoever is commissioning the piece removes that clause, he says, “and I try to put it back in”. Morrel knows this is a losing battle, primarily because demanding a site be forever unchanged would “inhibit the process of being awarded a commission” and because new owners—even the same owners—may seek to change the site at some point.

It has been a losing battle when artists have made the case in US courts that locations where their site-specific works are placed should not be altered in ways that change their artworks’ meanings. In 2001 sculptor David Phillips brought a VARA lawsuit when Fidelity Investments, owner of a park in south Boston for which he had created a series of site-specific sculptural elements, decided to install a new walkway through the park and relocate his sculptures to a park in a different state. The south Boston park overlooked the water, and “the pieces I created were relevant to a seaside area”, the artist says. Even so, in 2006 the US Court of Appeals ruled that federal law “does not protect site-specific art”.

In Europe, however, laws that protect artists’ works from intentional damage and destruction may extend to the sites where they are located. In December, Paris’s Musée du Louvre agreed to restore a neutral pale paint on the walls of a gallery in which Cy Twombly had created a ceiling mural in 2010, removing the brown paint that had been applied to the walls as part of a redecoration that also replaced the original limestone flooring with a wood parquet. The estate of the artist, who died in 2011, had sued the museum, claiming the changes altered Twombly’s mural.

According to Remi Sermier, a lawyer in Paris and former legal adviser to the French Prime Minister for cultural matters, France’s almost 100-year-old artists’ moral rights statute and subsequent case law decisions give artists there the right to challenge aesthetic changes to a place where a site-specific work is located.

“The change in the room’s decoration in which Twombly had painted the ceiling infringed on the respect due to the artist’s work and constituted a breach of the artist’s moral rights,” Sermier says. He adds that, “given the tendency of French courts to be very protective of artists’ rights, the Louvre was far from certain to win this case”.