In a defeat tinged by cautious hope, an accord has been reached to remove Elyn Zimmerman’s 1984 sculptural installation Marabar from the headquarters of the National Geographic Society (NGS) in Washington, DC, but to keep it intact and move it to a new location.

The nonprofit Cultural Landscape Foundation in Washington, which had enlisted art world figures to fight the demolition of the site-specific work, says the work will be reinstalled at the new site at the NGS’s expense.

“We are pleased that a resolution has been reached that the artist can support and that will ensure a safe future for Marabar,” says Charles A. Birnbaum, president and chief executive of the foundation, “and we’re grateful to National Geographic for being a strong and generous collaborator in this process.”

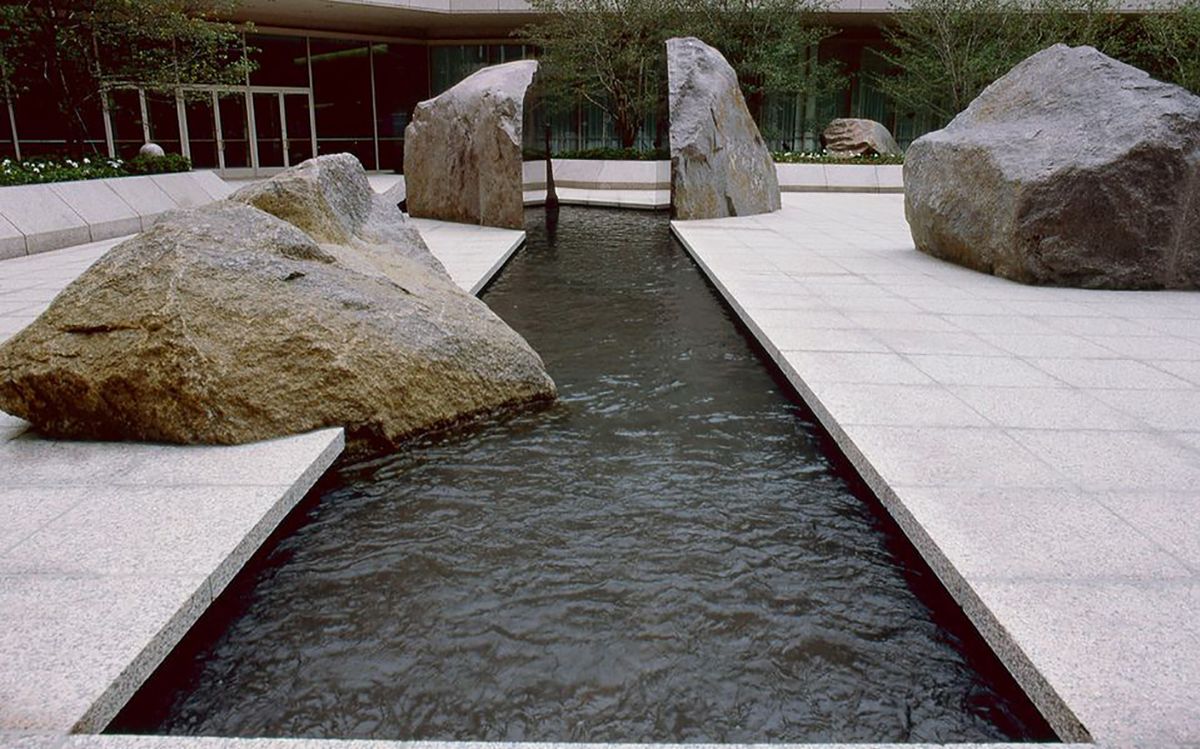

Marabar features a 6ft-by-60ft reflecting pool set on a plaza amid five red granite boulders. Seven other boulders designed by the artist are positioned throughout nearby gardens at the NGS headquarters. The society plans to remove the work so it can build an entrance pavilion on the plaza and an events space as part of a broad renovation project intended to greet a wider public.

The accord between the artist and the society aligned with a public meeting today by the District of Columbia’s Historic Preservation Review Board in which it reaffirmed an August 2019 decision to approve the society’s renovation concept and the removal of Zimmerman's installation. In making their case for removal, NGS representatives emphasised the agreement recently reached between the society and the artist to find a new location.

The board, which oversees historic neighbourhoods in Washington, also rejected the idea that the 1984 sculptural installation was worthy of protection as part of Washington’s 16th Street Historic District, whose “period of significance” is dated from 1815 to 1959.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation had previously argued that dismembering and relocating a site-specific installation like Zimmerman’s amounted to demolishing it. Art world figures had also protested the removal of the work, describing it variously as a “masterpiece” and a jewel. The foundation had appealed to the review board to reconsider its May 2019 decision to greenlight the NGS renovation.

“It was only within the past week that National Geographic’s architects, Hickok Cole, stated that the installation would have to be moved as part of the plaza redesign even if it were to ultimately remain in its original location as part of the renovated campus,” Birnbaum told the review board today. “This was new and very consequential information that changed the nature of the discussion between the artist, the Cultural Landscape Foundation and National Geographic, and led to this resolution.”

In a telephone interview, Zimmerman said that she had long feared that the sheer weight of the boulders in her installation would risk serious harm to them if moved. The turning point in negotiations came last week, she confirms, when the NGS determined that there was no prospect of retaining even some of the work's elements as part of its construction project. “I do believe that if we had worked together from the beginning, it might have had a different outcome,” she adds, however.

Zimmerman says she is grateful to the Cultural Landscape Foundation for its advocacy, but that “you can only do so much” in protecting public art. “It's endowed with moral right in most places in Europe and Canada,” she says. “In the US, it's just thought of as property. Over the course of the last 10 months, I have heard from so many artists who have had their works moved or destroyed.”

The architecture firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) recruited Zimmerman in the early 1980s to create Marabar when it was designing a building for the society’s complex, which has seen several additions since then. Her installation has won plaudits for its elegance and visual relationship to its surroundings.

In a letter submitted to the review board, the artist says that the monumental weight of her installation led to “an educated fear" that moving the largest rock components “could “physically destroy them”. “The three largest rocks at the east end of the pool near the SOM building together weight over 500,000 pounds," she writes.

Zimmerman now seems reconciled to the installation’s relocation. “I have been assured by NGS that I will have an active role in overseeing the removal, transportation and eventual installation of the components of Marabar on a new site which will be carried out at National Geographic expense,” she says in a statement.

The artist has already rejected a proposal by NGS to relocate Marabar to city-owned Canal Park in southeast Washington, built on a landfill on a canal that the artist says might not be able to support the sculptures. Zimmerman says that she and her advisors will explore possible sites in gardens tended by museums, colleges and universities, and private entities.