An archaeologist documenting painted carvings in Egypt has reconstructed the working methods of the ancient artists who created them. The research, published in the journal Antiquity, reveals how Egyptian artists organised their work, and that apprentices received on the job training from masters. Although archaeologists already understood the production stages of Egyptian art, it is rare to find evidence for it in finished works.

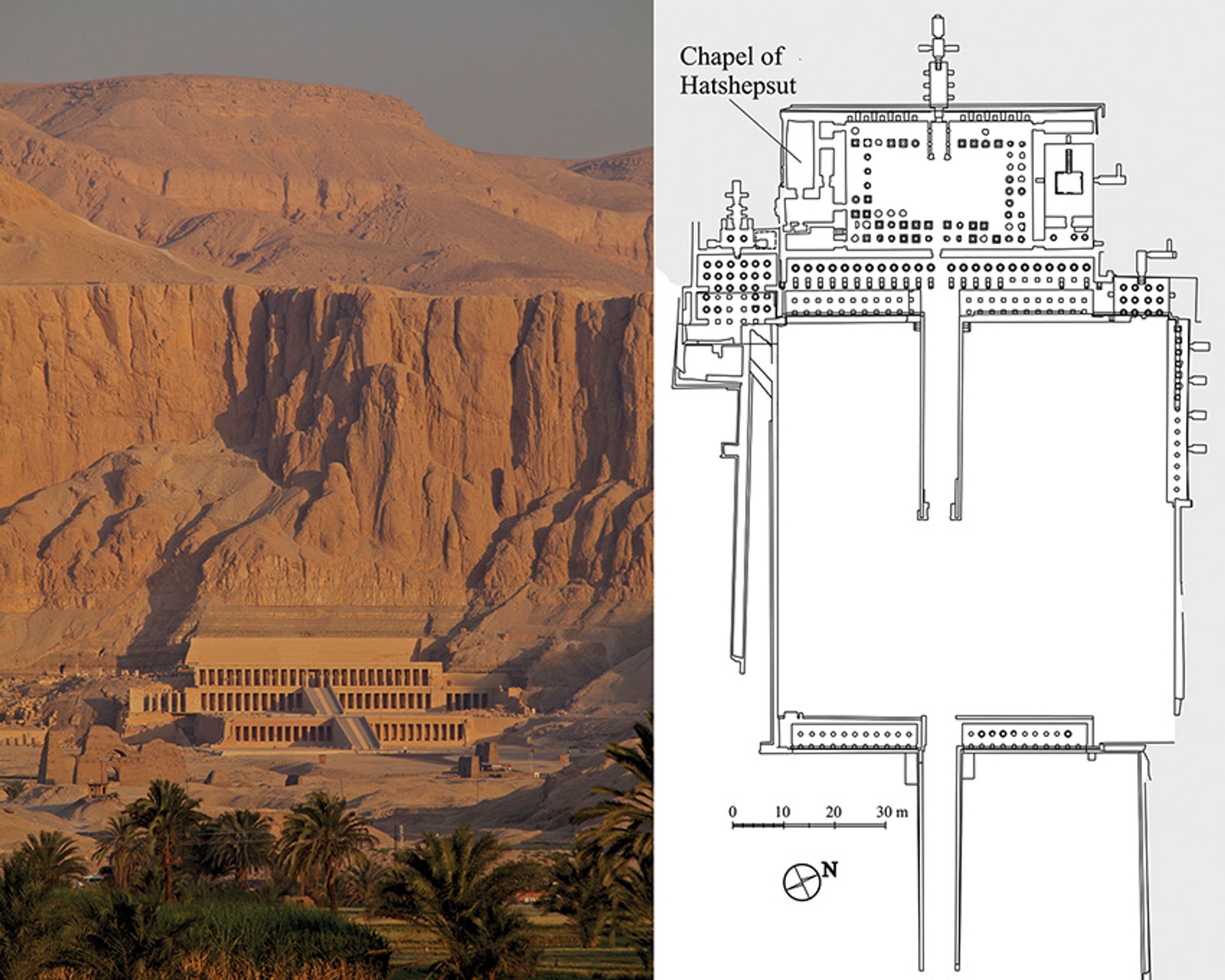

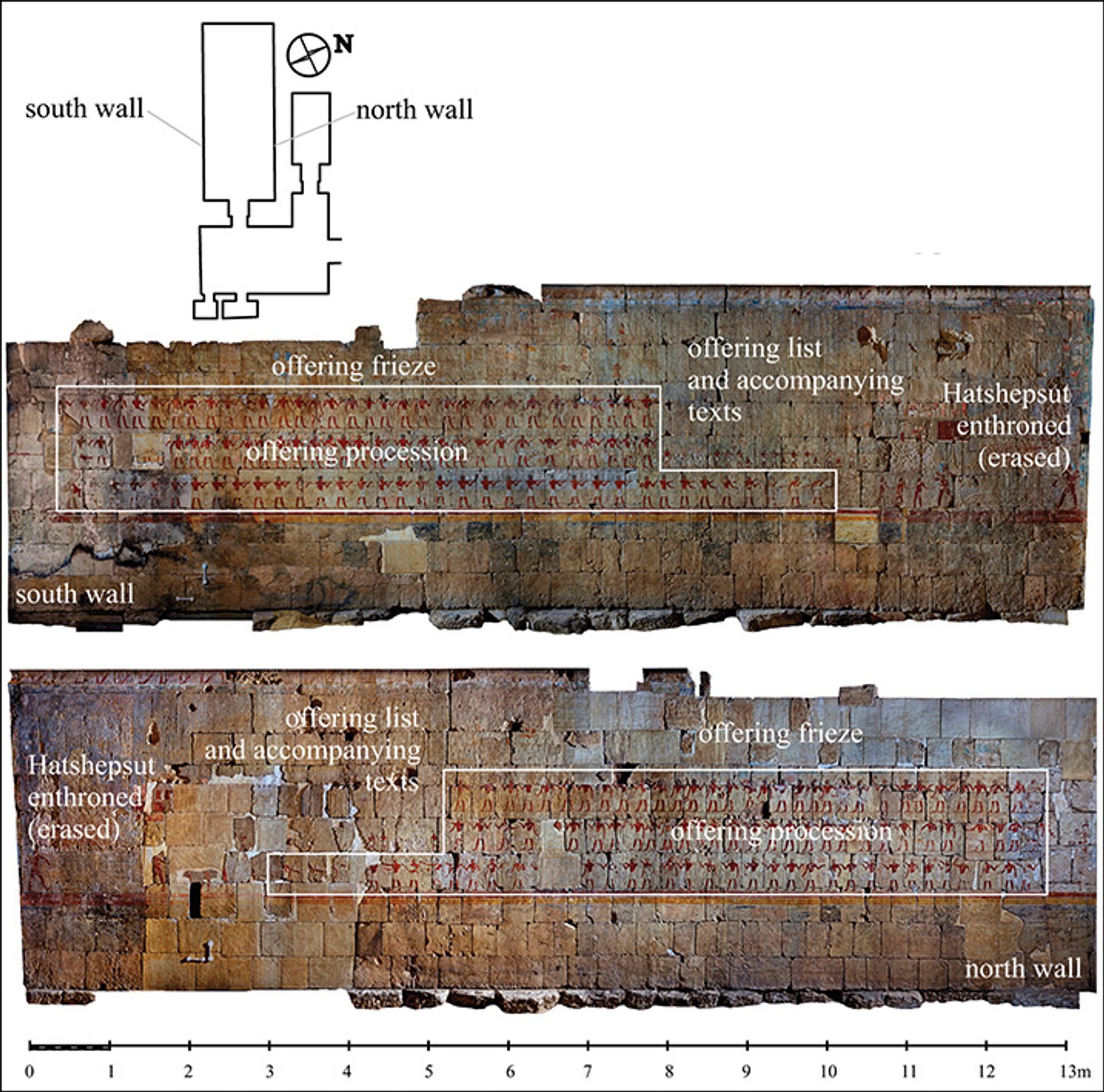

The reliefs cover the walls of a chapel within the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut—a female pharaoh who reigned from around 1473-1458 BC—and show a procession of 200 offering bearers, split over three registers across two walls. The temple stands on the west bank of the Nile at Luxor, close to the Valley of the Kings.

The Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari © Photo: M. Jawornicki; plan by T. Dziedzic

“The numerous figures displaying repetition of certain features, along with their exceptional state of preservation, created a unique opportunity to have a closer look at the people working in the chapel, on the technological process of their work, its organisation and its conditions,” says Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska, an archaeologist from the University of Warsaw, Poland, and author of the research paper.

Stupko-Lubczynska found that less-experienced artists carved the figures’ torsos, arms, and legs, while master sculptors worked on the faces and corrected mistakes. Both masters and apprentices carved the figures’ wigs, because each took a long time to complete. It also appears that the artists were divided into two crews, each working on their own wall. This led to differences in the quality of the work and some of the artistic choices made.

The Chapel of Hatshepsut, with offering scenes on the south and north walls © Photo: J. Kosciuk & M. Jawornicki; plan by T. Dziedzic

The carvings also shed light on how apprentices were trained. Archaeologists previously thought that artists received training away from ongoing projects, but this was not the case at Hatshepsut’s temple. Stupko-Lubczynska’s examination revealed that masters corrected apprentices’ mistakes and allowed them to carve sections alone. In one register, an apprentice carved the wigs on a line of figures. In other cases, both master and apprentice worked on the same wigs.

“One of these wigs, mostly done by a master and only partly by a student, demonstrates a virtuosity that is not met elsewhere, in a sense [saying], ‘Look how you have to do this!,’ even though it was rather impossible for a beginner to achieve that level,” Stupko-Lubczynska says.

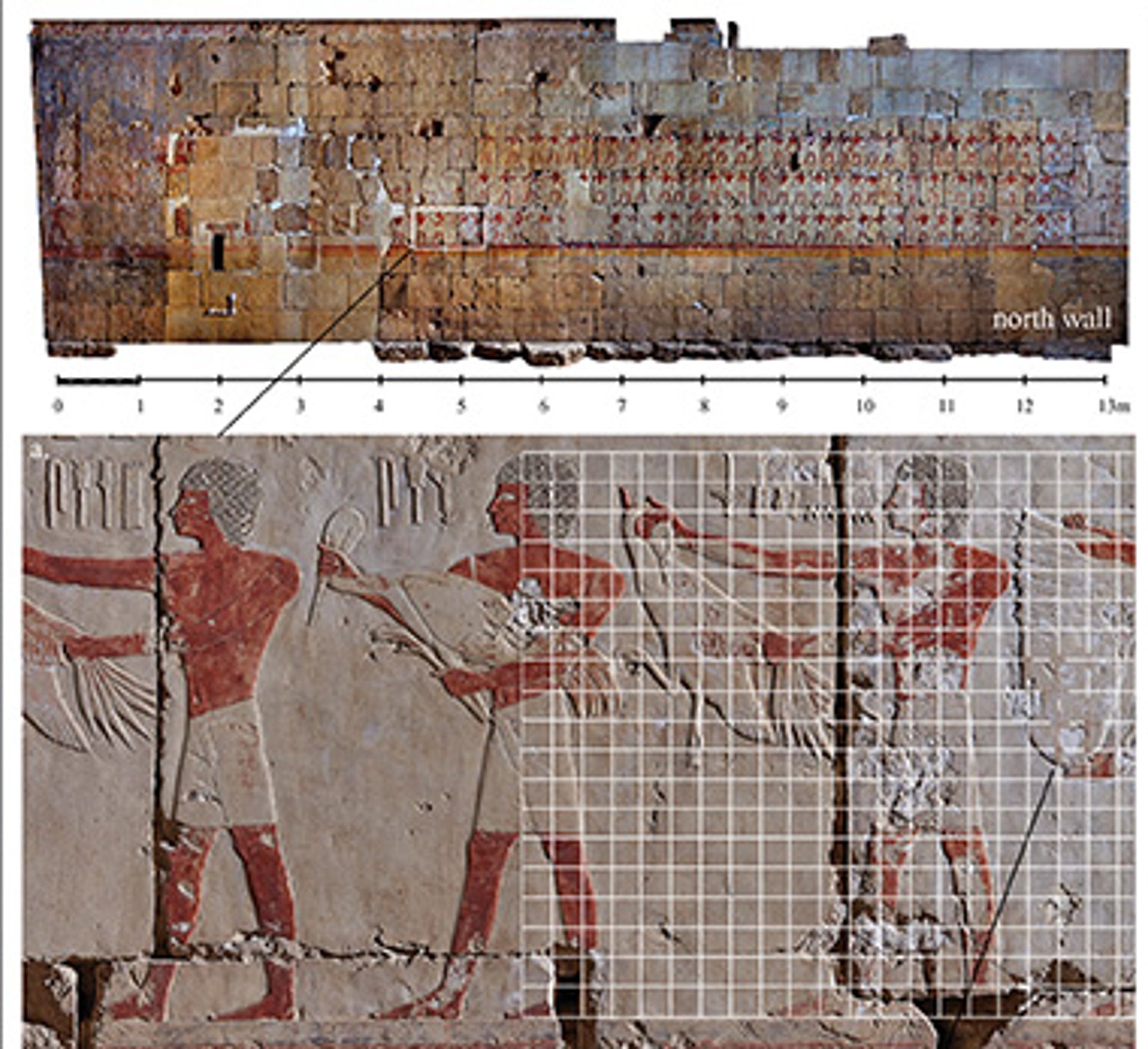

Remains of a square grid in the Chapel of Hatshepsut and its reconstruction for the entire figure of an offering-bearer © photo by J. Kosciuk & M. Jawornicki; grid reconstruction by the author)

There were surprises too. Normally, every phase of the carving work obliterates the preceding stages—so, for example, executing the reliefs destroys evidence of the drawing stage, Stupko-Lubczynska says. “It was thus a great surprise to spot in the chapel a trace of a square grid, which was used to transfer a pre-planned composition from a portable medium (papyrus or tracing board) onto a wall.”

Documenting the ancient reliefs “introduced an experiential approach,” which allowed the team to identify with the ancient sculptors and experience their working conditions and joy of creation, Stupko-Lubczynska says. “I am sure that they must have been satisfied when a given element was carved right, frustrated when not, and maybe, just as we did, they were leaving the nicest elements, such as faces, ‘for dessert’—to be carved after the rest was done.”