New research into Hubert van Eyck’s contribution to the Ghent Altarpiece (1432) is helping a painter about whom little is known to emerge from obscurity and the shadow of his talented younger brother, Jan.

Hubert died in 1426, before the altarpiece was completed. No other paintings by him are known, but it has long been acknowledged that he contributed to the Mystic Lamb, which was made for St. Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent.

In 1823, a Latin quatrain was found under overpaint on the frame. It read: “The painter Hubert van Eyck, a greater man was never found, started this work. His brother Jan, second in art, completed this arduous task at the request of Joos Vijd. He invites you, on 6 May [1432], with this verse to behold what was done.”

Adoration of the Lamb: heads attributed to Hubert van Eyck (in yellow), to Jan van Eyck (in red) and heads attributed to Hubert and reworked by Jan (in yellow and red) © Sint-Baafskathedraal Gent, www.artinflanders.be, foto KIK-IRPA

The altarpiece is undergoing research and restoration initiated by Belgium's Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in 2012. The work has so far focussed on the lower register of the altarpiece, including the Adoration of the Lamb and side panels.

It has yielded a number of important findings, such as the discovery that under many layers of varnish applied over the centuries, there was also a layer of overpainting dating from the 16th century that obscured much of Jan van Eyck’s work. And in 2020, restorers confirmed that the quatrain inscription on the frame was original, which had long been in doubt.

Now scholars have identified an elaborate underlying painting that they have attributed to Hubert van Eyck. It has compositional differences to the final painting: a natural spring in the middle panel, for instance, was later painted over by his brother with the Fountain of Life.

Hubert painted the sky, a hilly landscape with a few buildings, cities on the horizon and a meadow. Jan painted over the landscape and added recognisable motifs to the cities on the horizon, such as the tower of Utrecht Cathedral and the Church of Our Lady in Bruges. Some of the figures in the work were painted by Hubert and left untouched by Jan: others are recognisably by Jan’s hand.

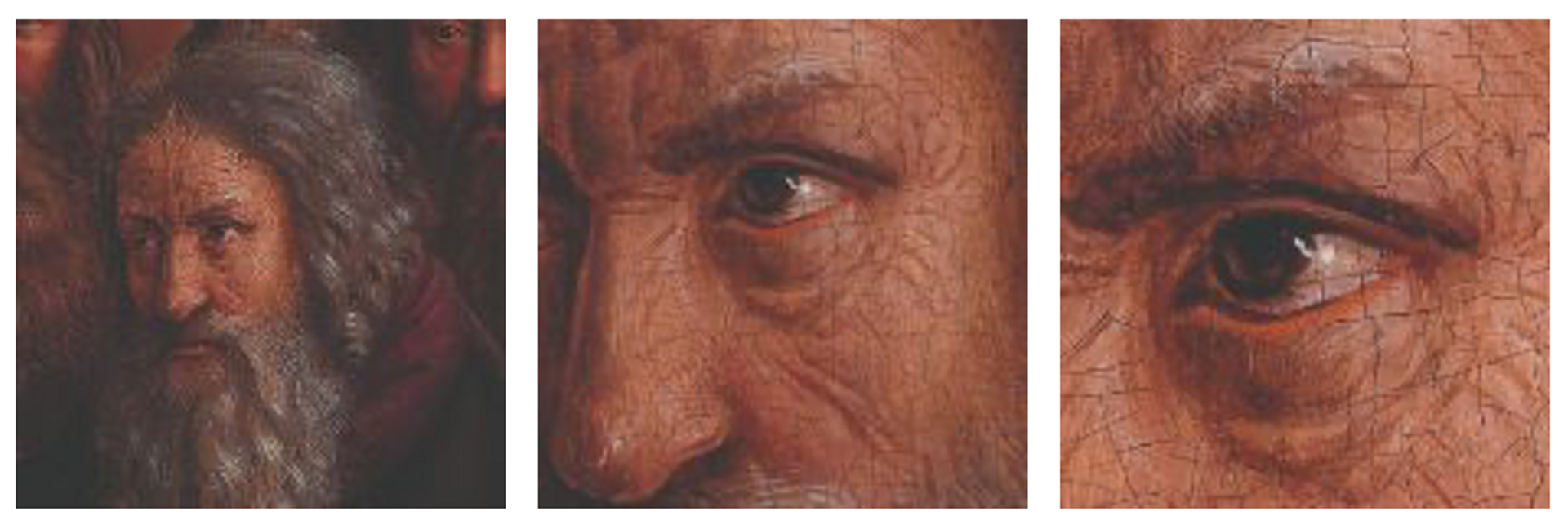

Head attributed to Jan van Eyck, head in close-up and a close-up of the eye. © Sint-Baafskathedraal Gent, www.artinflanders.be, foto KIK-IRPA

“We actually think that Hubert made the underdrawing, had already started working on it in paint, but that he had to stop the work at a certain point,” says Griet Steyaert, a restorer and art historian at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. “Jan then finished it off.”

The research, according to the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, “brings clarity to an old enigma and opens the door to a new chapter in the study of the Flemish Primitives—the search for other paintings by Hubert van Eyck.” The artist, it said, “could be the missing link between pre-Eyckian painting and the radically innovative Ars Nova of his younger brother Jan van Eyck.”

The painstaking restoration will continue on the upper panels of the altarpiece in 2022

The findings will also inform investigations of the upper register of the Ghent Altarpiece, which is to be restored and analysed starting next year, with funding from the Flemish Department of Culture, the Flanders Heritage Agency and the Baillet Latour Fund.