Restoring the Ghent Altarpiece may well exceed the years it took for Flemish brothers Jan and Hubert Van Eyck to create their wondrously detailed 12-panel masterpiece, from the mid-1420s to 1432. Since October 2012, Belgium’s Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA) has led a transformative €2.2m altarpiece conservation project in full view of the public, within a specially constructed laboratory at Ghent’s Museum of Fine Arts.

Marking the end of the project’s second phase, the five lower interior panels—including the central Adoration of the Mystic Lamb—will return to their home in St Bavo’s Cathedral on 24 January after a three-year treatment. The eight outer panels, restored during a first phase from 2012 to 2016, will come back to the museum in February, as exceptional loans for an exhibition in honour of Ghent’s “Year of Van Eyck”.

The altarpiece has been an iconographical puzzle for generations of art historians, its mystery compounded by the lack of archival information on the Van Eyck brothers. Despite the wealth of prior research conducted on the altarpiece, it was only during the KIK-IRPA restoration that scientists made an astonishing discovery: beneath the layers of yellowed and cloudy varnish, around 70% of the outer panels was obscured by 16th-century overpainting.

“This overpainting had been done so early on, and following the shapes of the original, with very similar pigments that had also aged in a similar way, that it was not actually visible on the technical documentation when the altarpiece first came in for treatment,” recalls Hélène Dubois, the head of the restoration project. “And nothing like this had ever been observed on early Netherlandish painting.” The discovery came as “a shock for everybody—for us, for the church, for all the scholars, for the international committee following this project”, she says.

The lower interior panels of the altarpiece have been restored © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, Belgium

Analysis confirmed the overpainting could be removed without damaging the original because an earlier layer of varnish “was acting as a buffer between the two”, Dubois says. X-ray fluorescence scans showed the underlying work was still “in very good condition”. Church wardens and the committee of experts gave their approval for the overpainting to be stripped away, a painstaking process using solvents and surgical scalpels.

Behold the lamb

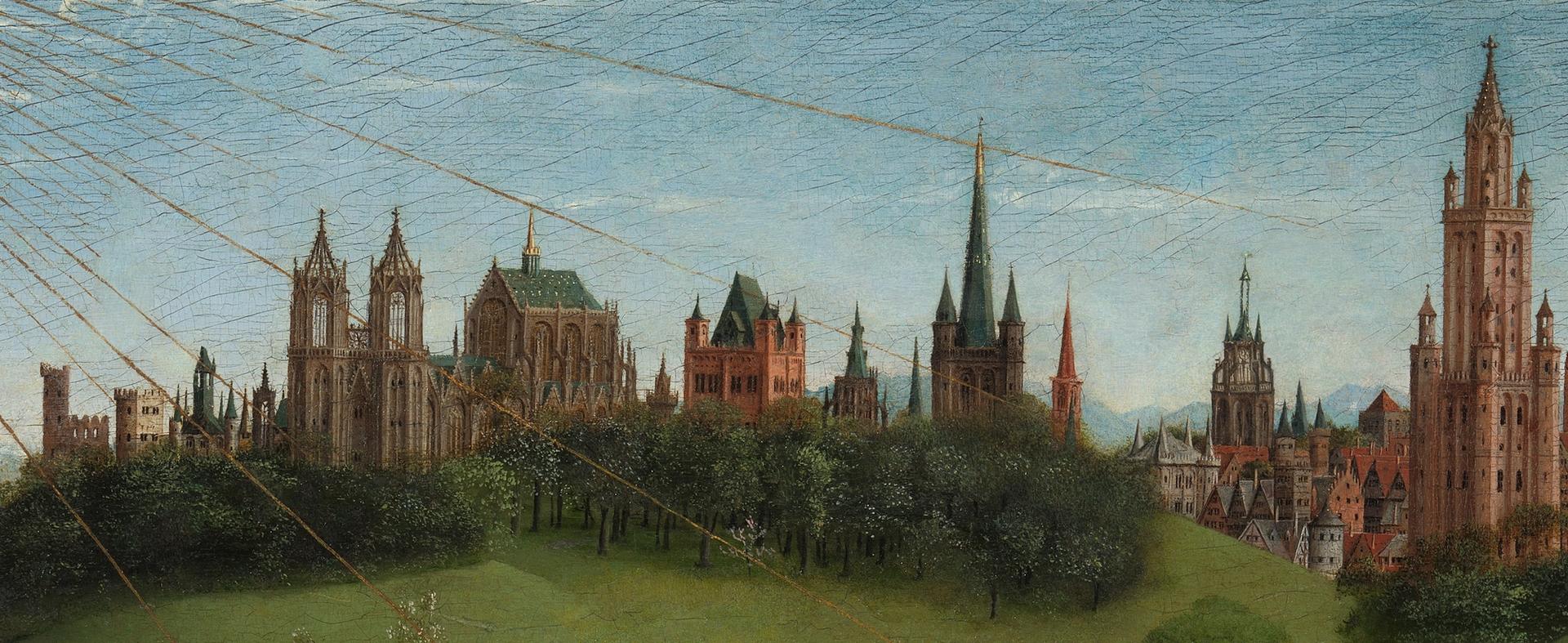

These 16th-century additions had covered around half of the panel featuring the sacrificial lamb, the symbol of Christ. Removing a blue hill on the horizon, for instance, revealed a trio of miniature buildings in the style of Medieval Ghent. The conservators consulted architectural historians on how best to reconstruct partially damaged areas. They also reinstated the crystalline look of the draped robes worn by the pilgrims worshipping the lamb, which had been softened in the overpainting.

Architectural historians were consulted by the conservators on how best to reconstruct partially damaged areas Image: St Bavo’s Cathedral; © Lukasweb; photo: KIK-IRPA. Restorers: © KIK-IRPA

Image: St Bavo’s Cathedral; © Lukasweb; photo: KIK-IRPA. Restorers: © KIK-IRPA

Most surprising of all was the lamb’s humanised face, which emerged beneath its more animal 16th-century appearance. The original lamb has a more “intense interaction with the onlookers”, Dubois says, adding that art historians and theologians will continue to research why the Van Eycks chose this “cartoonish” depiction—a striking departure from the painting’s precise naturalistic style. “Botanists can actually identify every plant in there,” Dubois points out. “The ones that couldn’t be identified—those were overpaintings.”

The humanised face of the lamb was disguised by a 16th-century overpainting across the central panel Image: St Bavo’s Cathedral; © Lukasweb; photo: KIK-IRPA. Restorers: © KIK-IRPA

The lamb before restoration Image: St Bavo’s Cathedral; © Lukasweb; photo: KIK-IRPA. Restorers: © KIK-IRPA

The 16th-century layer is believed to date from September 1550, when a Ghent chronicle records that two prominent painters “washed” and “kissed” the altarpiece, a phrase in local dialect that can mean “cleaning, improving, correcting”, Dubois says. Her doctoral research on the altarpiece argues that the pair’s adaptations were connected to the Habsburg court’s promotion of the Catholic church at a time of rising Calvinism. The overpainting was complete by 1557, when Michiel Coxcie made a copy of the altarpiece for Philip II.

By the mid-1500s there was also a straightforward need to “refresh a painting that had become dulled with use in the cathedral”, Dubois says. Under the overpainting, the conservation team found dirty varnish and clumsy touch-ups applied directly to the wood panel. “Tiny blisters” in the painted surface had probably been caused by church candles.

A number of palm branches carried by the female martyrs on the right-hand side proved to be later additions, which were removed

The group of female martyrs before restoration

Armed with magnifying glasses, size-zero brushes and reversible watercolour and resin-based glazing paints, the conservators infilled losses and fine abrasions exposed after the removal of the overpainting, building up luminous colours and volume through minute brushstrokes. The restoration has brought out many subtle details, such as the wrinkled neck of the grey horse in the painting of the knights of Christ and the different textures of mud, rocky ground and wet sand on which the figures walk in the lower panels. The challenge was to reveal the quality of the Van Eycks’ original work “without erasing every single mark of time”, Dubois says.

By contrast, Jef van der Veken’s 20th-century copy of the lower-left panel depicting the Just Judges—which was stolen from the cathedral in 1934—has received only minimal attention. Badly flaking paint had already been consolidated in 2010, but conservators decided not to alter the panel’s yellowed appearance. “Of course, the contrast is much stronger now the others have become so brilliant, but it’s part of the history of the painting,” Dubois says.

Whose hand where?

Pending further funding, KIK-IRPA aims to publish new research in 2020 that addresses the long debate over the altarpiece’s authorship. According to a Latin inscription on the frame, the painting was started by Hubert and completed by Jan after his brother’s death in 1426.

The restorers observed many compositional changes that pre-date 1550 and are consistent with Jan’s “technique and vision”, as well as “weaker” elements that could be the work of studio assistants, Dubois says. “We were much better able to characterise different phases of execution so we can see that large zones were finished and then completely redone in the manner of [Jan] Van Eyck.” She warns, though, that the absence of works attributed to Hubert makes it impossible to identify his hand.

The painstaking restoration will continue on the upper panels of the altarpiece in 2021

The restoration will continue into a third phase that tackles the upper sequence of interior panels, possibly beginning in 2021. This might prove “even more complex”, Dubois thinks, because the gold backgrounds behind the figures of God, the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist are “very damaged” and God has been “completely overpainted”. But there is no guarantee that KIK-IRPA will continue working on the project, as the church wardens must launch a new European tender and secure additional funds from the government of Flanders.

For Dubois, the most groundbreaking aspect of the project so far has been its “complete openness” to the public, demystifying the conservation process through talks at the museum and a dedicated website. With 80% of the funding coming from the government, “it’s only fair that we inform people about what’s happening”, she says.

In Belgium, where the Ghent Altarpiece is regarded as “the ultimate masterpiece”, expectations for the restoration are high. But Dubois is confident that the “incredible quality” of the painting will meet them. “You think you know Van Eyck because it’s such a part of the culture,” she says. “But now you can really see [his work] and that will be a revelation for people.”