The Flemish Old Master Jan van Eyck was described by Giorgio Vasari as an alchemist who invented oil painting, he was a skilled diplomat sent on secret missions, and his mastery was such that his appearance in the annals of art history has sometimes been compared to the arrival of a comet from outer space. Myths can sometimes be created to explain such genius but a new show opening this week at Ghent’s Museum of Fine Arts—the largest ever on the artist—will place his works front and centre.

Van Eyck: an Optical Revolution brings together around half of the 20 to 22 autograph works in existence, with several remarkable international loans as well as sections of the Ghent Altarpiece (1432, also called Adoration of the Mystic Lamb)— the masterpiece that Van Eyck created with his brother Hubert—on loan from Ghent’s Saint Bavo’s Cathedral.

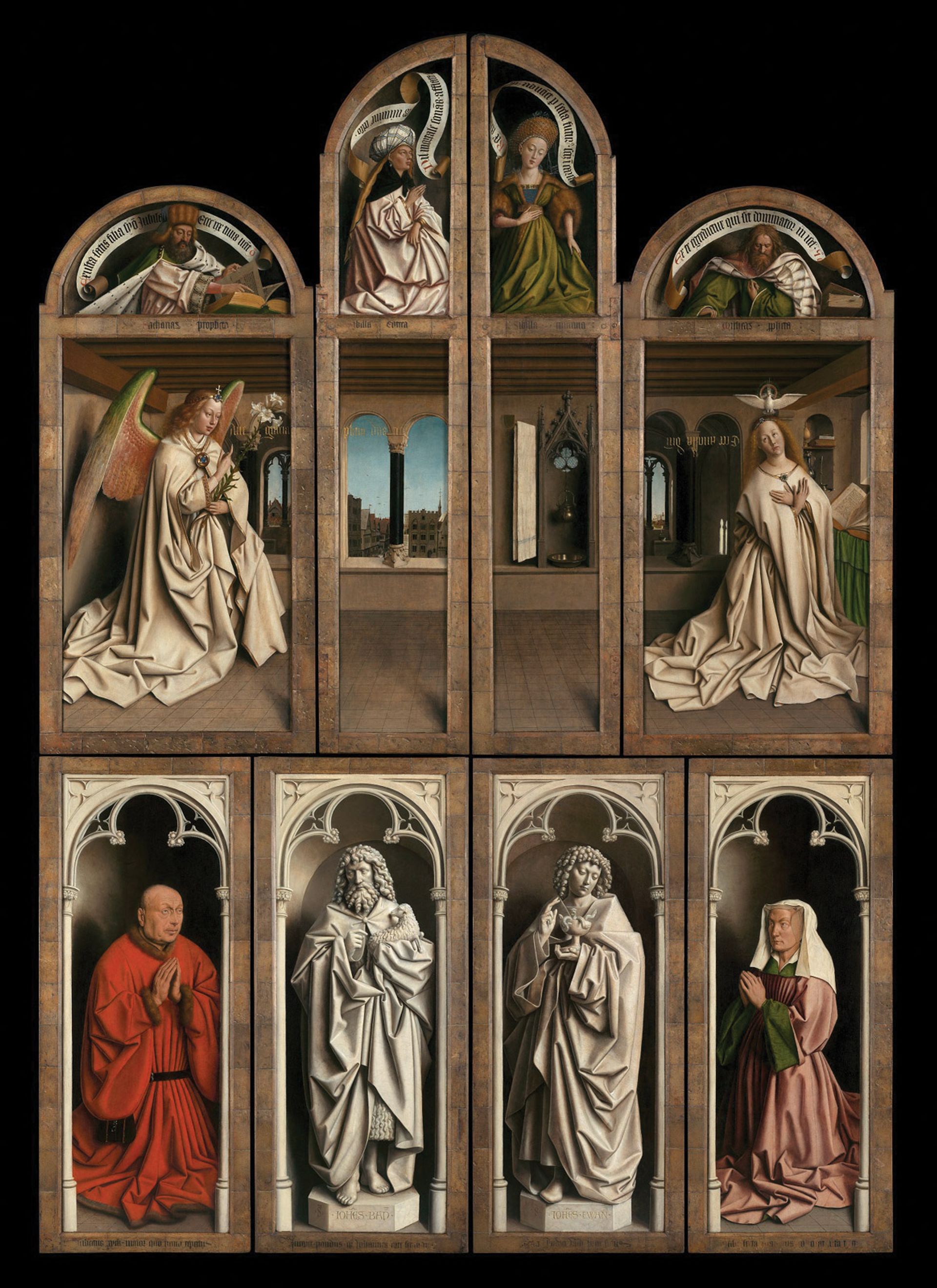

The idea of putting together such an exhibition came about after the museum began hosting the €2.2m public restoration of the Ghent Altarpiece. The outer panels, which were restored during the first phase of the project, between 2012 and 2016, will be included in the show along with two unrestored interior panels of Adam and Eve.

The outer panels of the Ghent Altarpiece (1432) © www.lukasweb.be – Art in Flanders. Vallotton: photo: Reto Pedrini.

The exhibition is a “once in a lifetime opportunity to see the panels up close,” says the exhibition’s co-curator Frederica Van Dam. Although the altarpiece has had a lively and itinerant past—it was removed from Saint Bavo’s during the Reformation, stolen during the Napoleonic Wars, returned in 1919, two panels were stolen in 1934 (one is still missing), it was moved around again during the Second World War—the only time that any of its panels (the Adam and Eve pair) have been included in an exhibition was in 1902. Furthermore, the cathedral has said this will be the last time that the panels from the altarpiece will be loaned out for an exhibition.

For the show, the panels will be installed in pairs—Adam and Eve, the grisailles of the two St Johns, the Annunciation panels, the two interior and exterior views, and the donor portraits—with a thematic exhibition organised around them. “This way it is much easier to have a dialogue between the panels and other Van Eyck works,” Van Dam says. “Previously, before the restoration, the Ghent Altarpiece was a bit different from the other Van Eyck panels, colour-wise but also stylistically,” Van Dam says. “And now we know why—because of severe overpainting in the 16th century. This is the first time that we can see that these panels really do match the oeuvre of Van Eyck.”

“He perfected the oil paint technique [to create] effects of depth, light, texture and so on”

Two further works have been “freshly restored” ahead of the exhibition: Portrait of a Man (Leal Souvenir) (1432) from London’s National Gallery, which reveals a “big difference in that you can observe much more of Van Eyck’s qualities”, and Portrait of Baudouin de Lannoy (around 1435) from Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie, where “now you can see the fur and feel the different hairs in the fur [hat]”, Van Dam says.

Little is known of Van Eyck’s early years, and this, coupled with the lack of surviving works by his predecessors, led to his impact being compared to the arrival of a comet from the darkness. He was probably born around 1390 in or near Maaseik, now in eastern Belgium. Records indicate that he worked in the Hague for John III Duke of Bavaria-Straubing, before being appointed court painter to Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, who ruled over large areas of the lowlands. Van Eyck lived in Lille and later, in the early 1430s, settled in Bruges where he established his workshop and remained until his death in 1441.

The Annunciation Diptych (around 1433-35) demonstrates Van Eyck's ability to render sculptures in two dimensions Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Van Eyck’s period as court painter to Philip the Good meant that not only did he have money and resources, but also access to libraries, the intelligentsia of the time, and the opportunity to travel. He was said to be a skilled diplomat and was sent on several secret missions, whose details still remain unknown. “He had [many] more opportunities to see things than the average person during the late Middle Ages,” Van Dam explains. It is very probable that he went to Jerusalem, and he may have travelled to Spain and Italy too. We do know for certain that he travelled to Portugal in 1428 to paint Phillip the Good’s future bride, Isabella of Portugal. “He had the chance to observe another landscape than that which we are used to here in the Netherlands,” Van Dam says. “You can see palm trees in the Ghent Altarpiece, for example.”

“He had this unbelievable hand-eye coordination,” Van Dam says. Van Eyck’s exceptional powers of observation, enriched by his travels, are one of the key explanations that Van Dam and her fellow curators have put forward as to “why Van Eyck is such a genius” and why they called the show Optical Revolution.

“Van Eyck must have had theoretical knowledge as well,” Van Dam says. “What we see in his paintings is not only possible because of pure powers of observation.” He was said to have studied “geometry” by the 15th century historian Bartolomeo Fazio. “This sounds, at first instance, a little bit weird, because if you look at Van Eyck’s paintings, he was not considering mathematical perspective like his contemporaries in Italy did,” Van Dam says. But “we realised that geometry was a general name for different branches of science of which optics was one of the most important studies”.

Then there is Van Eyck’s handling of his chosen medium. Although he did not invent oil painting—as Vasari claimed—“he perfected the oil paint technique,” Van Dam says. It had been around for centuries, but the addition of a drying agent at the time made a huge difference. “In this way he could make the technique much more manageable and could work in different layers, both opaque and transparent” to create “effects of depth, light, texture and so on”.

Van Eyck's Saint Francis of Assisi Receiving the Stigmata (around 1440) is on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; John G. Johnson Collection, 1917

Visitors will be able to compare Van Eyck to “his most talented contemporaries from Italy”, thanks to some exceptional loans, including Masaccio’s The Virgin and Child (1426) from the Galleria degli Uffizi and Fra Angelico’s Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata (around 1430) from the Vatican. The latter will be shown in a gallery with Van Eyck’s two almost identical versions of Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata (around 1435-40 and around 1440), on loan from Turin’s Galleria Sabauda and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Another loan highlight, used to demonstrate the skill with which Van Eyck was able to render sculptures in two dimensions, is a trio of recently restored alabaster figures from the Rimini Crucifixion Altarpiece (around 1430). They will be shown alongside the pair of grisaille St Johns from the Ghent Altarpiece and Van Eyck’s The Annunciation Diptych (around 1433-35), from Madrid’s Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza. Although the Rimini altarpiece “sounds Italian, it was really made here in the Netherlands,” Van Dam says. There is no evidence that Van Eyck saw these specific works, but “it is very likely he would have seen the same type of sculptures”, she adds.

Getting this many Van Eyck works all together was a “difficult” task “because they are the most treasured objects in collections”, Van Dam says. The exhibition is supported by, among others, the City of Ghent who launched a campaign called “OMG! Van Eyck was here”—and visitors will no doubt rejoice that so many Van Eyck works are heading there.

• Van Eyck: an Optical Revolution, Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent, 1 February- 30 April