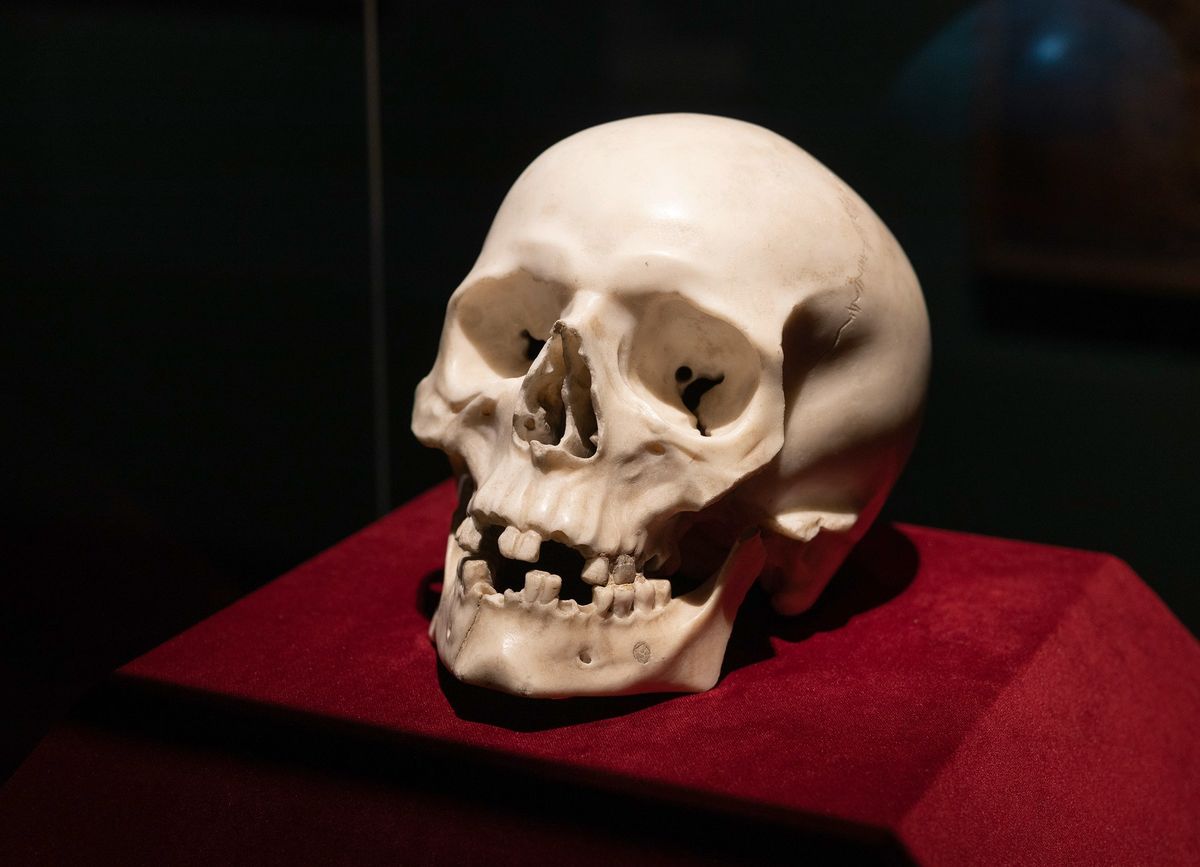

A life-sized skull, skilfully sculpted of Carrara marble to look as realistic as possible, was for many years on show at Schloss Pillnitz, a palace south of Dresden. While scouting for art for a Caravaggio exhibition, the curator Claudia Kryza-Gersch decided it would be an ideal exhibit. She had it brought to the restoration workshop of the Dresden State Art Collections.

“There was something about seeing the object out of its glass case,” Kryza-Gersch says. “I was so overwhelmed. It’s scary—it has an aura.”

The skull was part of the collection of the Chigi family in Rome, which Augustus the Strong (the ruler of Saxony from 1694 as well as the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania for a time) acquired in 1728. The trove comprised 164 sculptures of antiquity, and four contemporary Baroque works. For decades, the death head was part of the archaeological collection, whose curators were less interested in the more modern works, Kryza-Gersch says. “It was just not on the radar.”

But once in the restoration workshop, the skull caused a stir. “Everybody had the same reaction to it,” Kryza-Gersch says. “We were standing around a table, looking at it. The question of course was—who made it? And since it has Roman provenance, someone jokingly said ‘maybe it’s a Bernini?’”

Kryza-Gersch began to research the Dresden inventories and archives. In the correspondence of Raymond Le Plat, Augustus the Strong’s chief art buyer, she found a mention of the “famous death head” and the name of the artist—Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

“Wow,” she says. “Our jokes were proven right.”

Guido Ubaldo Abbatini's Pope Alexander VII with Bernini's skull (1655-56) © Art Collection of the Sovereign Order of Malta, Rome (Sovereign Order of Malta - Grand Magistry); photo: Nicusor Floroaica

She combed the Chigi archives and Bernini literature to fill in the gaps. Three days after Alexander VII was appointed Pope in 1655, he commissioned a sarcophagus and the death head from Bernini. That makes it unlikely that the sculpture was by Bernini’s workshop, Kryza-Gersch says. The preceding years had been troubled ones for the sculptor, then in his late 50s, and he had fallen out of favour.

“He had to grab the opportunity and make it work,” she says. “If you get a commission from the new pope in that situation, you do it quickly and you do it yourself.”

Just after Alexander VII ascended to the papal throne, the plague broke out in Rome. Many of the measures he introduced at the time are now familiar to us all—masks, quarantines and lockdowns. He kept the sculpted skull on his desk, and the sarcophagus under his bed as reminders of death’s proximity.

The death head is now on view to the public in a cabinet exhibition that opens today at the Semperbau in Dresden, called Bernini, the Pope and Death (until 5 September). Among the two-dozen exhibits is a portrait of Alexander VII laying his hand on the skull. This 1655-56 oil painting, on loan from the Sovereign Military Order of Malta in Rome, is by Bernini’s pupil Guido Ubaldo Abbatini.

“This time, all the pieces came together like a beautiful puzzle,” Kryza-Gersch says.