A work by Vasudeo S. Gaitonde has, once again, broken the record for an Indian artist at auction after his 1961 painting from the collection of the dancer Aditi Mangaldas made £3.9m (with fees) at SaffronArt in Mumbai. This comes just six months after he last made this record.

SaffronArt's sale on 11 March, which also achieved the highest price for the Baroda Group painter N.S. Bendre, marked the first major auction of Modern and contemporary South Asian art since a promising September season.

It left hopes high for this week's Asia Week New York auctions at Sotheby’s and Christie’s.

On Tuesday, Sotheby's sold another Gaitonde work—a fresh-to-auction 1962 painting from the collection of Robert Marshak, a US physicist who helped develop the atomic bomb—bringing in $1.9m (with fees) against a high estimate of $1.2m. Several lots later, an austere Akbar Padamsee landscape nearly quadrupled its low estimate of $250,000 to make $927,5000 (with fees). In total 93 out of 101 (92%) lots sold, bringing in $7.1m—more than double the sale’s $3.3m low estimate—and a nearly 50% increase from last year.

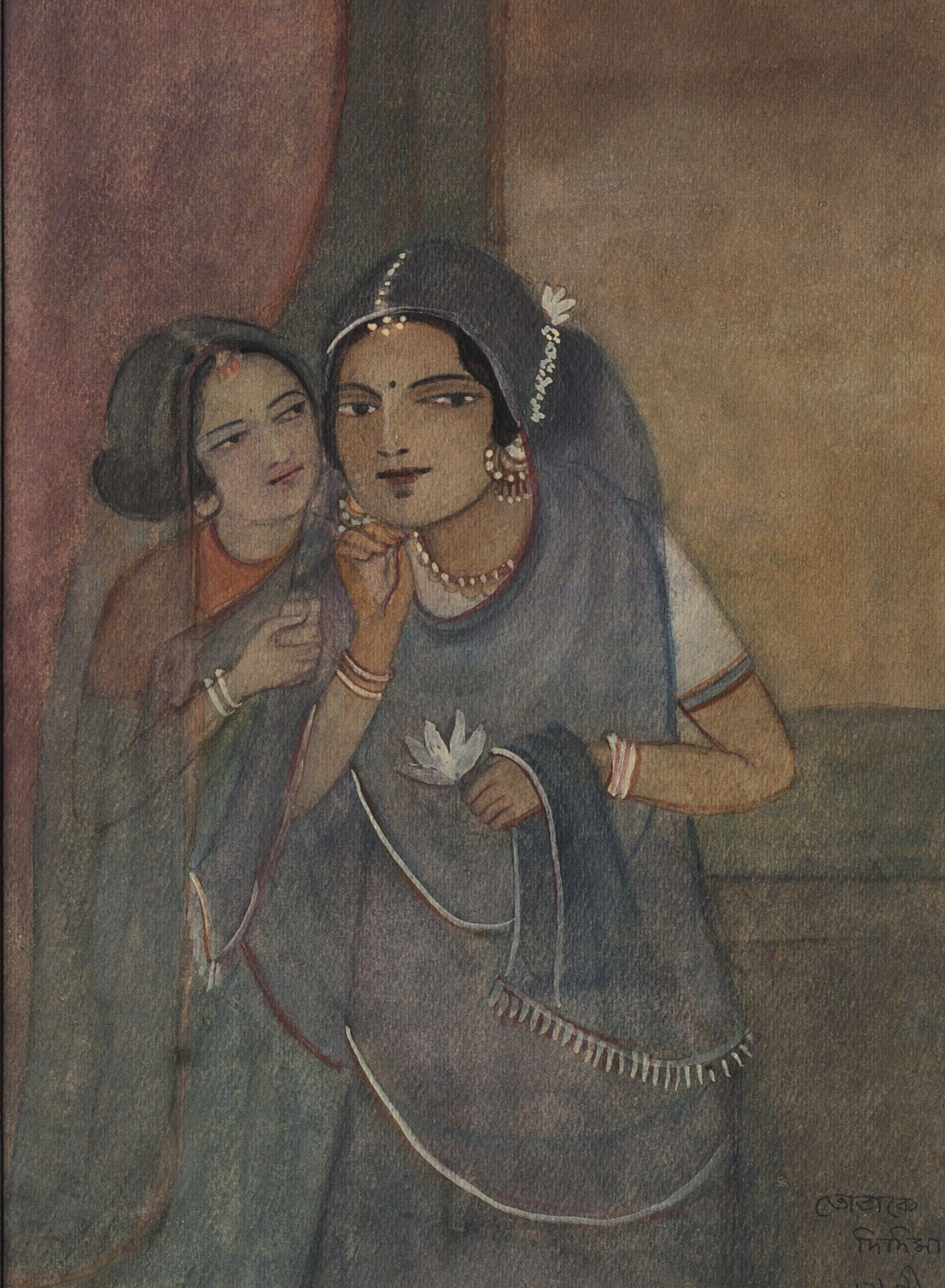

Sunayani Devi's Untitled (Dui Sakhee) Courtesy of Sotheby's

Records were set for seven artists, several of whom, such as Sunayani Devi and Manishi Dey, come from the Bengal School. Interest from art historians and institutions in this early 20th-century group of Indian nationalist artists has surged in the past decade, with prices steadily rising in tandem.

The head of sale Manjari Sihare-Sutin attributes Sotheby's continued success in the category in part to a policy of introducing approximately five to 10 new artists each year that have either never been featured at auction before, or are new to Sotheby’s.

“Most auction sales in this category focus on a small group of well-established artists. But we have worked to expand that roster, not only to include new names, but to rethink the accepted ideas of who has made contributions to Indian art,” Sihare-Sutin says.

But the next day, Christie's failed to match up, making just $4m (with fees) against its pre sale estimate of $5.8m-$7.1m (without fees) with a sell through rate of just 48%, or 57 out of 117 lots.

The first dozen lots moved quickly, including five works by the late Zarina, three of which hammered for well over their high estimates. But this energy soon flatlined by the time of the sale’s most anticipated item, a “rediscovered” portrait by Amrita Sher-Gil, India’s most expensive female artist at auction. Due to Sher-Gil's untimely death aged 28, her works rarely come to the market (this was her eleventh painting ever at auction), but the highest bid of $1.7m failed to meet the reserve.

Nishad Averi, head of sale, says that Christie’s is now in talks to sell the work privately, likely for around $2m.

Tyeb Mehta's Untitled (Confidant) (1962) Courtesy of Christie's

The sale's top lot, Family (1946) by Francis Newton Souza—a scathing depiction of poverty influenced by Souza's Marxist leanings—brought in $880,000 (with fees) against a high estimate of $600,000, while Tyeb Mehta's Untitled (Confidant) (1962) made $750,000 (with fees) against an estimate of $600,000-$800,000. Deepanjana Klein, Christie's international head of department for contemporary Indian & Southeast Asian art, confirms this is the same Mehta that The Art Newspaper reported as having been withdrawn from a private sale in autumn last year, following the positive results of September's auction season.

Three out of the six Krishen Khannas from the Banwell collection failed to sell, as did a gleaming set of metallic sculptures by Subodh Gupta, priced at $400,000-$600,000, which received a single bid at $220,000.

Benode Behari Mukherjee's Frying Fish (around 1953) Courtesy of Christie's

The latter half of the sale was devoted to a collection of 59 works by Benodebehari Mukherjee, being sold from the foundation of his late daughter, the artist Mrinalini Mukherjee. Despite Benodebehari's status as an influential art educator, only around two dozen of his works have so far appeared at auction. This provided a unique opportunity for Christie's to cement Mukherjee's place within the market, a task it struggled to achieve, as less than a quarter of these works managed to sell.

When they did, however, they attracted rare bursts of competitive bidding, as seen for the oil-on-silk painting Frying Fish (around 1953), which leapt past its high estimate of $50,000, to reel in the artists's record at $70,000, which previously stood at $40,000 made at Sotheby's in 2020. Similarly, three of Mukherjee's collage works, executed after he went permanently blind following a botched eye surgery, hammered for around their high estimates.

However, overly confident estimates for the drawings on paper, which were mostly priced between $2,000 and $10,000 and made up the bulk of the sub-sale, resulted in a poor overall performance, with most bidders evidently unwilling to pay in the high four figures for non-premium works by a less established name.

Although the headline statistics from Christie's sale may dampen a rising bullishness within the South Asian Modern market, they also belie some important successes—those of new faces and smaller records—that signal continued growth at a measured rather than a frenzied pace. And when one considers the spectacular boom and bust that defined the Indian art market of the 2000s, slow and steady somehow doesn't seem so bad.