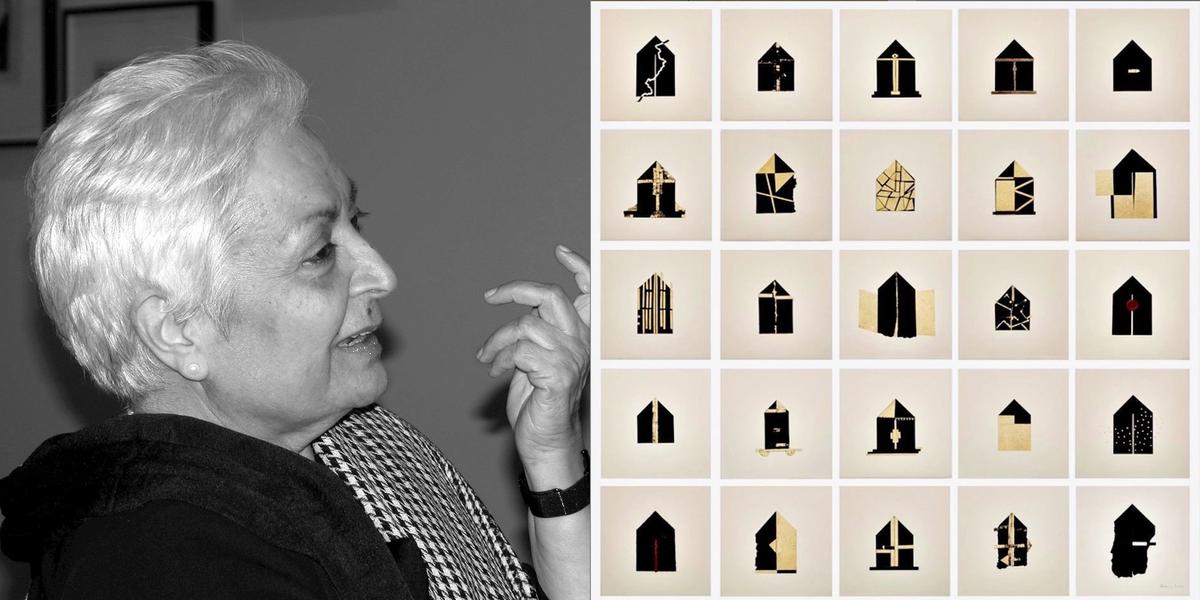

The Indian artist Zarina Hashmi, who has died aged 83, created minimalist works inspired by architecture and mathematics, putting an emphasis on “structural purity” according to New York-based Luhring Augustine gallery who represented her. Zarina, as she was known, was born in Aligarh, India, in 1937, receiving a degree in mathematics from Aligarh Muslim University in 1958 where her father was a history professor. She later studied woodblock printing in Bangkok, Tokyo and Paris before settling in New York in 1976.

As a printmaker, she worked in various media including intaglio, woodblocks, lithography and silkscreen, drawing on personal memories. “Her art poignantly chronicles her life and features recurring themes of home, displacement, borders, journey, and memory,” says a statement on the artist’s website. The Partition of India in 1947 in particular left a lasting impression. “I was ten years old when the partition took place. I only witnessed this event from this side (India), and after 60 years there are still aftershocks,” Zarina said.

In 2012, the first retrospective of her work, Paper Like Skin, was held at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. “Zarina emphasises the sculptural sensibility that underlies printmaking, originating in the carving of a woodblock or the assembly of a relief collage,” said an exhibition statement.

Here, artists, academics and curators pay tribute to the late artist.

Zehra Jumabhoy, associate lecturer, Courtauld Institute of Art, London

In a way, alongside Nasreen Mohamedi, Zarina was our first "cosmopolitan" superstar. And, it’s not coincidental that she should be chosen for this role, because for many a Euro-American curator, Zarina’s oeuvre represents an intellectually satisfying merger between "Eastern" philosophy, "Islamic" geometry and "Western" abstraction. Her use of "home" as a transitory concept also has a global resonance in today’s highly mobile world, as does her sense of exile and displacement, her ultimate homelessness.

But, there was another reason she was significant for South Asians, and I think that the outpouring of grief we have seen over her passing in the last three days is proof of that. For South Asians her life, as well as her art, was really a relic of a generation that has vanished post-Partition. She was an Indian Muslim; who spoke Urdu, whose works were about this Urdu-speaking generation of North Indian Muslim intellectuals, who centred around Aligarh university. This generation is no more. Urdu is dying in India; it is Pakistan’s national language. But even in the latter context, it does not represent an uncontested idea of "national culture" for Pakistanis. This aspect of her significance is ultimately untranslatable and it is difficult for non-South Asians to understand. Even more difficult is to explain how symbolically significant her work is to my generation—you see, we grew up with the after-effects of the 1947 Partition, but we never witnessed it. So Zarina and her work did the remembering for us.

Nada Raza, former curator at the Tate, London, and a doctoral student at the Courtauld Institute of Art

Raza organised an exhibition of Zarina’s work at the Ishara Art Foundation, Dubai, in 2019

Zarina worked with the simplest materials: paper, ink, metal, often at just a modest A4 scale. The work appears minimal, and its monochrome elegance easily found space on white cube walls. However, each motif, each symbol, emerged and was cleft from a deep knowledge and engagement with the cultures of Asia, with her language, Urdu, her own linguistic and cultural inheritance, rich with metaphor and allusion. She may have left Delhi for the US as a single woman seeking independence, but she remained completely absorbed in the aesthetic world of Aligarh, the intellectual culture that was disrupted by Partition. She often quoted [Palestinian poet] Mahmoud Darwish—she related closely to poetry and literatures of diaspora and exile.

The genius of her work was that while its forms might have a sort of universal modernist appeal, for those of us who can read the language, they opened up other worlds. When we acquired Letters From Home (2004) for Tate, we stood together and read the script of her sister’s letters which form part of the prints, describing the sale of their house, remembering each flowering plant in the garden. Incredible restraint and deep intimacy—that was Zarina. At the opening show for the Ishara Art Foundation, intended to address South Asian audiences in the United Arab Emirates, the series Home is a Foreign Place (1998) anchored the exhibition, describing perfectly the precarity of the untethered immigrant.

Alexandra Munroe, senior curator of Asian art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

The museum hosted Zarina’s retrospective Paper Like Skin in 2013

Zarina is gone. A great artist and a fierce, wise soul. We will miss her. The Guggenheim is honoured to have presented her show in 2013, and her suite of 1970s pin-hole works, which redraw the map of feminist art and serial minimalism, on view in our collection show now, to be celebrated when we reopen. We feel blessed that she is forever part of the museum. Her subject? Home, a site of longing, loss, borders, and impossible love. [Message posted on Instagram].

Munroe tells The Art Newspaper: Zarina came to the Guggenheim through Sandhini Poddar, our former Asian art curatorial colleague. In 2008, Sandhini led me to Zarina’s studio, in the thick of midtown’s garment district, to select work for our forthcoming show, The Third Mind, which explored the influence of Asian aesthetics on American art spanning the late 19th through 20th century. The show featured work by several Asian-born artists who lived and worked in the US, but of all, Zarina was then the least well-known. Zarina lived like a monk; her bed was a few feet away from her printing press, and her kitchen was a counter top piled high with roots and spices. But she hoarded splendid materials - hand-made papers from Japan and Nepal, sheets of gold leaf, fragile as a butterfly’s wing; and boxes of tools to bend paper to her will. She was a fierce soul shaped by what she lost and what she renounced: home. She was pleased by the Guggenheim’s presentation of her 2013 solo show, Zarina: Paper Like Skin, but really just wanted to get back to her studio. She was a thinker, alert to history’s pain, but the urgency of making things—her quiet acts of cutting, pasting, pressing—grounded her to the earth.

Shilpa Gupta, artist

Gupta's work was shown alongside Zarina’s at the Ishara Art Foundation, Dubai, in 2019

It was an honour to be paired with Zarina in such a sensitively curated show by Nada Raza for the opening of Ishara Art Foundation. She transcends genres and brings together beauty, text and form, with such an astute approach, leaving an incision in our hearts, mirroring the pain of lines drawn hastily in the subcontinent.

Hajra Waheed, artist

Zarina generously allowed us to share in her search, her daily surrenders and nightly dreams. She safe kept our Urdu, intricately mapped the distance between our separation and yearning, between what we can’t forget yet never return to. If language was indeed where she felt most at home, her fierce courage and commitment to spend her life building a lexicon of her own, continues to offer so many of us another respite to call home. I will always as I have, find refuge in her.

Sheena Wagstaff, Leonard A. Lauder Chairman, Modern and Contemporary Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (excerpt from blog)

Zarina was a remarkable human being. Ever focused on her art, she lived frugally, even ascetically, in a tiny Manhattan apartment; when a light bulb went out, she was known to neglect replacing it, relying sometimes on a candle's softer illumination.

Over copious lashings of first-flush Darjeeling tea and English biscuits, Zarina was intellectually generous and very well read; a conversation with her would range from deep knowledge of current American politics to poetry to a reminiscence of meeting Agnes Martin. She had a quiet wisdom born of a life in perceptive observation of humankind all over the world, and a fierce wit, sassy irreverence and hilarious sense of humor that turned any teatime into a party. Above all, her sense of what 'home' meant lay within her, in a deep belief in a spiritual life, that enabled her not just to come to terms with her permanent displacement, but also to serve as a trenchant, brilliant witness to our times.