During the protests that erupted across the US in May after the death of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police, many activists on social media shared images taken by the photographer Gordon Parks. In comparison with other documentary photographers of his generation, Parks remained a fairly unheralded name in the annals of photography, beyond the moniker of being considered the first black photographer to “break the colour line” in the US.

The documentarian first published many of these photographs in 1957, across eight pages in New York’s Life magazine, under the title The Atmosphere of Crime. Many of the images have never been exhibited, while several remained obscure. But now a new monograph, Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957, co-published by Steidl and the Gordon Parks Foundation, in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), brings fresh light to the work, which challenges the stereotypes about criminality that were pervasive in mainstream media at the time.

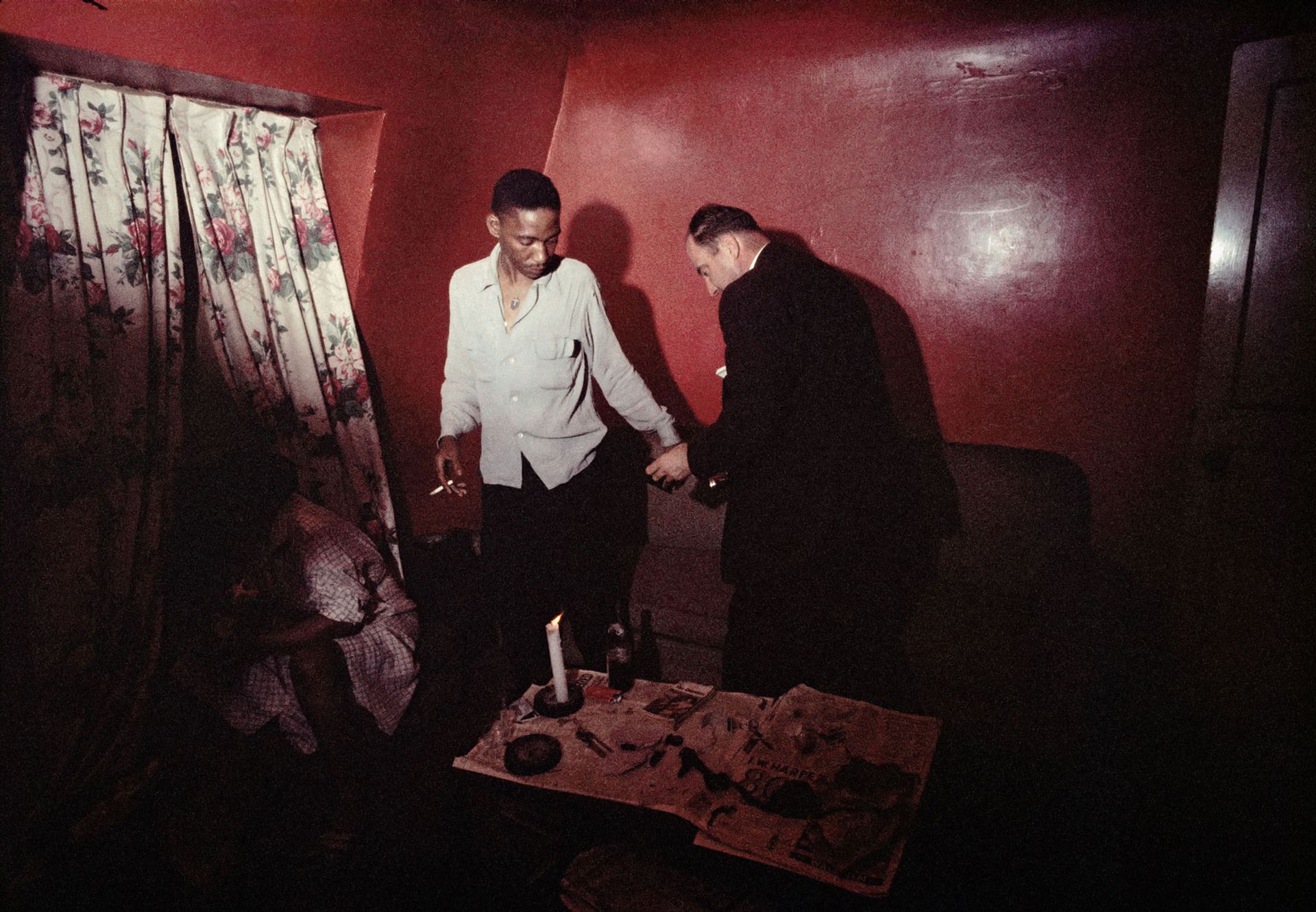

Gordon Parks's Untitled, Chicago, Illinois, 1957 © Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

MoMA is also due to exhibit part of the series after it acquired the full set in February. The museum’s director, Glenn Lowry, and Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr, the executive director of the Gordon Parks Foundation, write of the series: “It transcended the romanticism of the gangster film, the suspense of the crime caper, and the racially biased depictions of criminality then prevalent in American popular culture.”

“Brutality was rampant. Violent death showed up from dawn to dawn”Gordon Parks

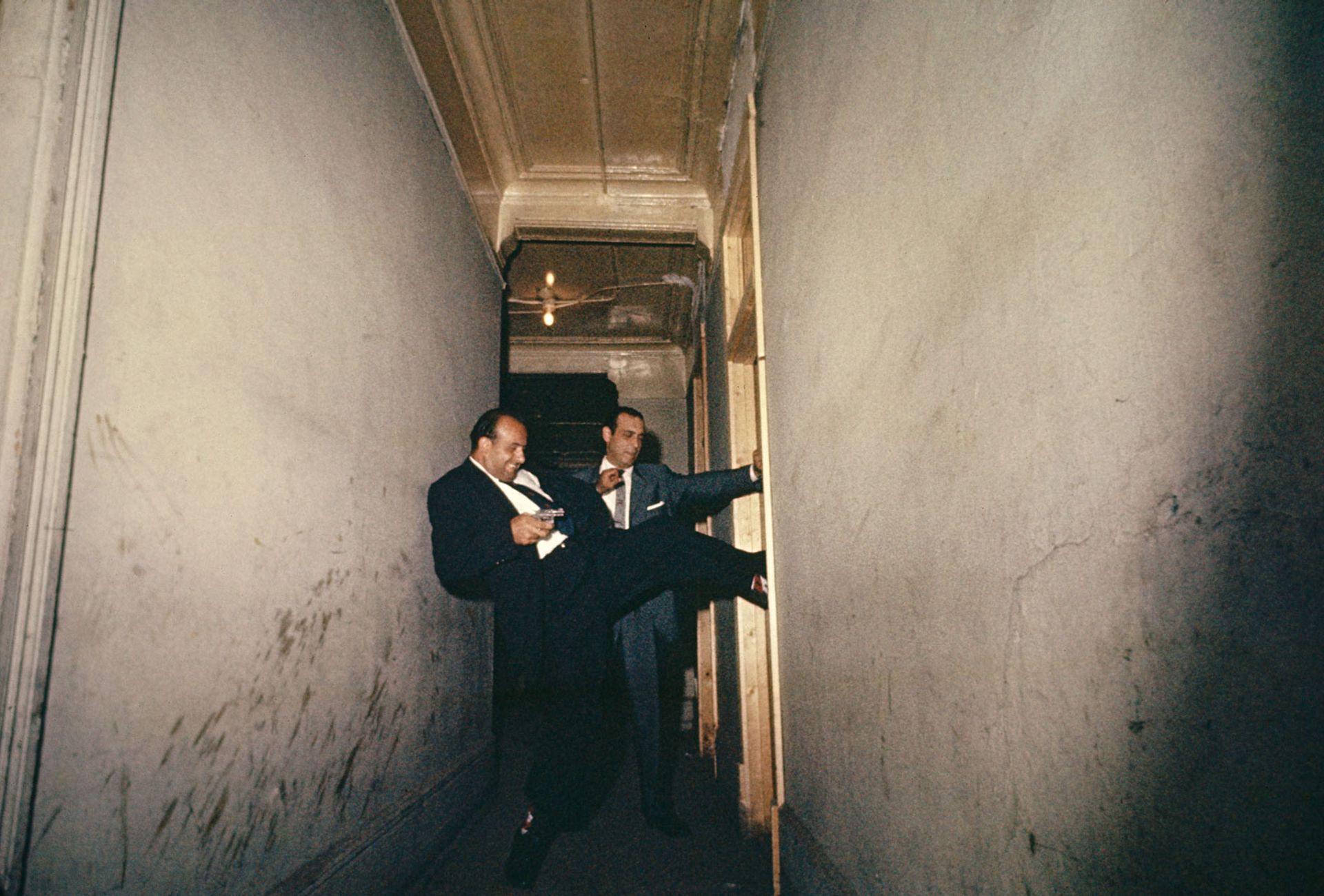

To create The Atmosphere of Crime, Parks embarked on a six-week journey across the US, photographing black neighbourhoods in New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles. He said of the work: “My assignment was to explore crime across America. It was a journey through hell. I rode with detectives through shadowy districts, climbed fire escapes, broke through windows and doors with them. Brutality was rampant. Violent death showed up from dawn to dawn.”

Gordon Parks's Untitled, Chicago, Illinois 1957 © Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

The series, when published, exposed mainstream understandings of black poverty, marginalisation and, crucially, how black citizens were treated by US police. They served to counteract enduring media stereotypes of black criminality, forcing Life’s readers to reassess their beliefs about an experience that even today garners little attention in US media.

Parks’s images became a recurring campaigning presence in the ensuing civil rights movement of the 1960s, which led to the Civil Rights Act and the desegregation of public institutions, including the dismantling of segregated schools. Their presence around the #BlackLivesMatter campaign today attest to their ongoing relevance.

Gordon Parks's Raiding Detectives, Chicago, Illinois 1957 © Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Parks remains probably best known for his work in movies, in particular Shaft (1971). He was born in Kansas in 1912, the youngest of 15 children and the son of a farmer. He attended a segregated school and almost died at the age of 11 when three white boys threw him from a height into the Marmaton River, knowing he could not swim. As a young man, he worked as a waiter in brothels, and as a singer and piano player while living in a flophouse in Chicago.

At the age of 25, after seeing photographs of migrant workers in a magazine, Parks felt compelled to buy a camera and found one in a pawnshop for $7.50. After teaching himself photography and honing his craft, he won the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1942, which gained him a position with the Farm Security Administration, a governmental agency that had been established to combat rural poverty in the aftermath of the Great Depression. He then worked as a freelance photographer for magazines such as Glamour and Ebony, until he was hired by Life magazine in 1948 as the publication’s first African American staff photographer. He remained at Life for more than two decades.

Gordon Parks's Untitled, New York, New York 1957 © Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Parks said in 1961: “Everyone must face the problems of humanity. My way of facing these issues is through photography. It is important because it can show, without needing words, everything that is wrong and can be improved.”

• Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957, Sarah Hermanson Meister (ed), Steidl, 120pp, €38 (hb)