The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York has acquired a full set of photographs by Gordon Parks from The Atmosphere of Crime series, a photographic essay examining crime in America he created on assignment with Life magazine in 1957. Along with 55 modern colour inkjet prints created from Parks’s transparencies, selected and bought in consultation with the Gordon Parks Foundation, the foundation has gifted a vintage gelatin silver print that matches a work already in MoMA’s collection, given by the photographer in 1993. Around 15 pieces from the series will go on view in a dedicated gallery on the fourth floor in May, along with an excerpt from his classic 1971 film Shaft and works by other artists from the collection, as part of the next reinstallation of the permanent galleries.

The acquisition comes through years of conversations with the Gordon Parks Foundation, which has been organising in-depth exhibitions of the photographer’s work at major museums since his death in 2006. “When Sarah Meister [MoMA’s curator of photography] and I began speaking a few years ago about how the museum could make a major acquisition, it was about what body of work would really have the most impact to what's going on in the current world,” says Peter Kunhardt, Jr, the foundation’s executive director. “And we both felt that The Atmosphere of Crime was so relevant, not only because so much hasn’t changed today in our criminal justice system and with police brutality and violence, but also because the work is in colour.”

Colour photography was prohibitively expensive to produce outside of commercial projects at the time Parks first shot the series, Meister explains, and only a selection of images from the series were printed in colour in Life. “The transparencies that Gordon Parks made have been held back for a number of years for the right institution to thoughtfully put together an exhibition and book,” Kunhardt adds. The catalogue, published by Steidl with essays by Meister, Bryan Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, and the art historian Nicole Fleetwood, who also wrote Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, includes all the images from the acquisition.

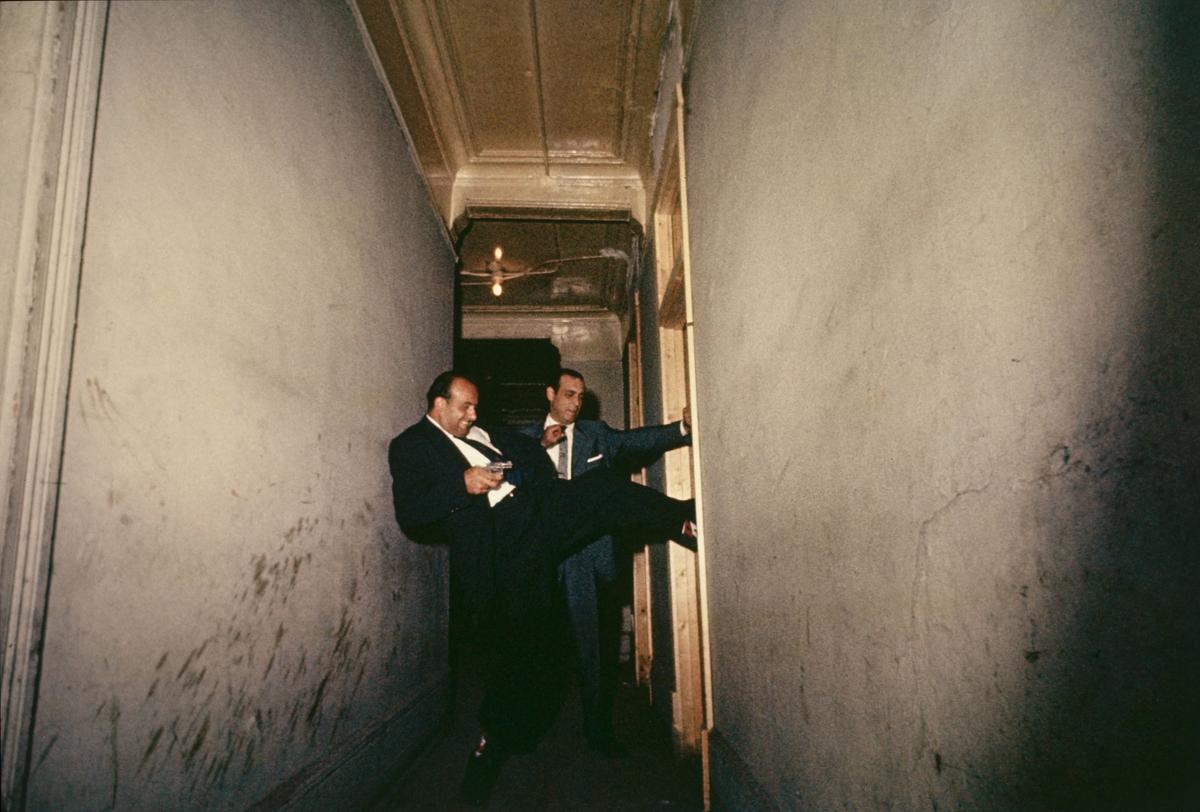

Gordon Parks, Drug Search, Chicago, Illinois (1957, printed 2019) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Family of Man Fund. © The Gordon Parks Foundation

The museum already had a few works by Parks in its collection, including the dramatic black and white image Raiding Detectives, Chicago, Illinois, which the photographer gave to MoMA in 1993 in honour of Edward Steichen. “That has been an incredibly important piece in the collection, and it both encapsulates the story in Life magazine and yet is an incredibly inadequate representation of it, in that it is black and white as Parks printed the series at that time for himself,” Meister says. “One of the things that was always missing was this one story in depth and what that presence in the collection allows you to do.” In addition to the full set of colour prints of The Atmosphere of Crime photos, ranging in size between 16 by 20 and 20 by 24 inches, the foundation also gave MoMA an untitled vintage black and white print from the series showing the justice system from the prisoner’s point of view.

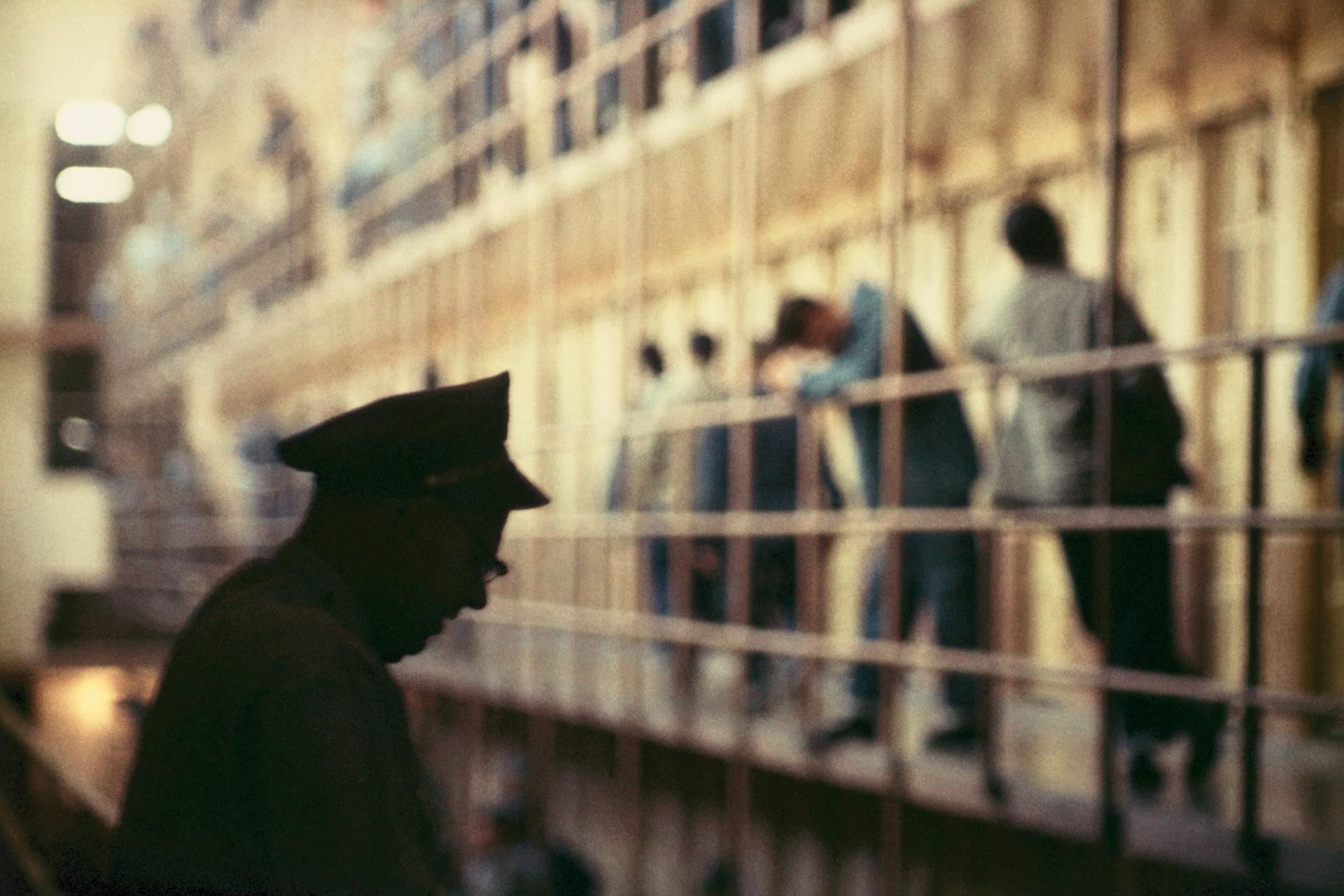

The subject of the American justice system is “urgent and timely for a whole number of reasons”, Meister says, and displaying the work of an “incredibly thoughtful, talented artist, grappling with what it means to represent crime in photography… gives people the tools to question how these images of incarcerated people, and how these assumptions that go along with them, need to be challenged”.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Chicago, Illinois (1957) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Gordon Parks Foundation. © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Writing in the exhibition catalogue, Stevenson says Parks “consistently humanized people who were meant to be objects of scorn and derision,” recognising “the disconnect in traditional crime narratives with a larger history of bias against the poor and people of color. It’s clear that he wanted to use his camera to complicate the view held by most Americans.”

Parks himself did this on an even bigger stage in the classic 1971 film Shaft, which MoMA plans to screen a clip from in the gallery. The popular movie, in which the actor Richard Roundtree portrays the hip and heroic African American detective John Shaft, who takes down a gang of white criminals, serves as “as a counterpoint” to the photographic series, Meister says, to show how Parks’s “own thinking and approach [to the subject] both evolves and is expressed through a different medium”.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, San Quentin, California (1957, printed 2019) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Family of Man Fund. © The Gordon Parks Foundation

The exhibition at MoMA will further expand Parks’s view of the justice system by displaying other works that take on crime by artists including Danny Lyons, Weegee and Dorothea Lange, as well as 19th-century mug shots compiled by early police departments. “What's striking to me is when you look at the history of photographs of criminals in MoMA's collection, the vast majority of them are white,” Meister says.

Kunhardt believes the lasting power of Gordon’s images comes from his ability to “empathetically relate to his subjects—it was all about trust,” he says. “It was all about capturing the moment to make a difference, to make sure that people's voices were heard.” That is how his work has transcended its journalistic origins to be acquired by a museum like MoMA, Kunhardt adds. “He really did see himself as an artist and a humanitarian.”