"Content is king,” the Microsoft founder Bill Gates famously proclaimed in a 1996 essay about the internet. It has now become a cliché, but for commercial galleries, content in all its myriad forms—in real life and online—is the new frontier.

Lucas Zwirner, head of content at David Zwirner gallery and moderator of the gallery’s podcasts, Dialogues, which launched in 2018, says he is “always hesitant” about the word "content". “If I think about our operations, of course there’s this content rush happening in the world, but we really want to be culture participants and producers,” he emphasises.

Dialogues is a podcast produced by David Zwirner Courtesy of David Zwirner

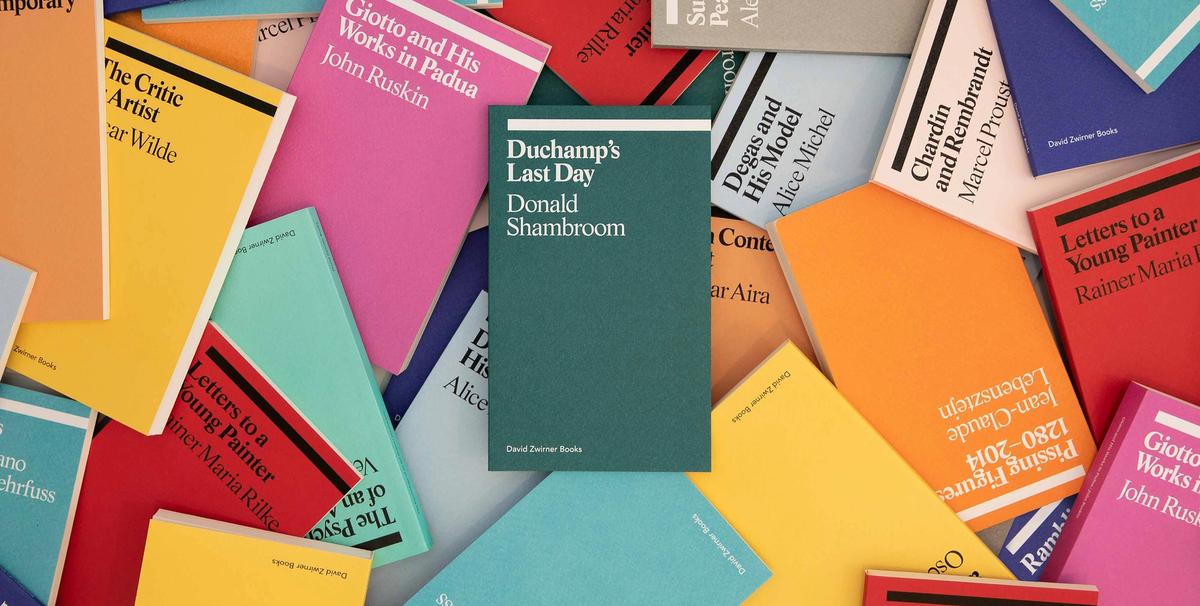

Zwirner, who was the editorial director of David Zwirner Books between 2014 and 2019, describes the gallery’s media initiatives as a “trifecta of publishing”, consisting of traditional print media, digital media, which is at “a nascent stage for everyone”, and what he calls “event-driven publishing”. The gallery recently partnered with the New York Review of Books on a series of free talks examining the intersection of power and culture. Building audience participation is key, Zwirner says.

As at David Zwirner, print publishing remains a key strand of Hauser & Wirth’s operations. It even launched a standalone publishing headquarters and bookshop in Zurich in June 2019, essentially creating a “showroom for our publishing arm”, as Michaela Unterdörfer, the gallery’s director of publications, describes it.

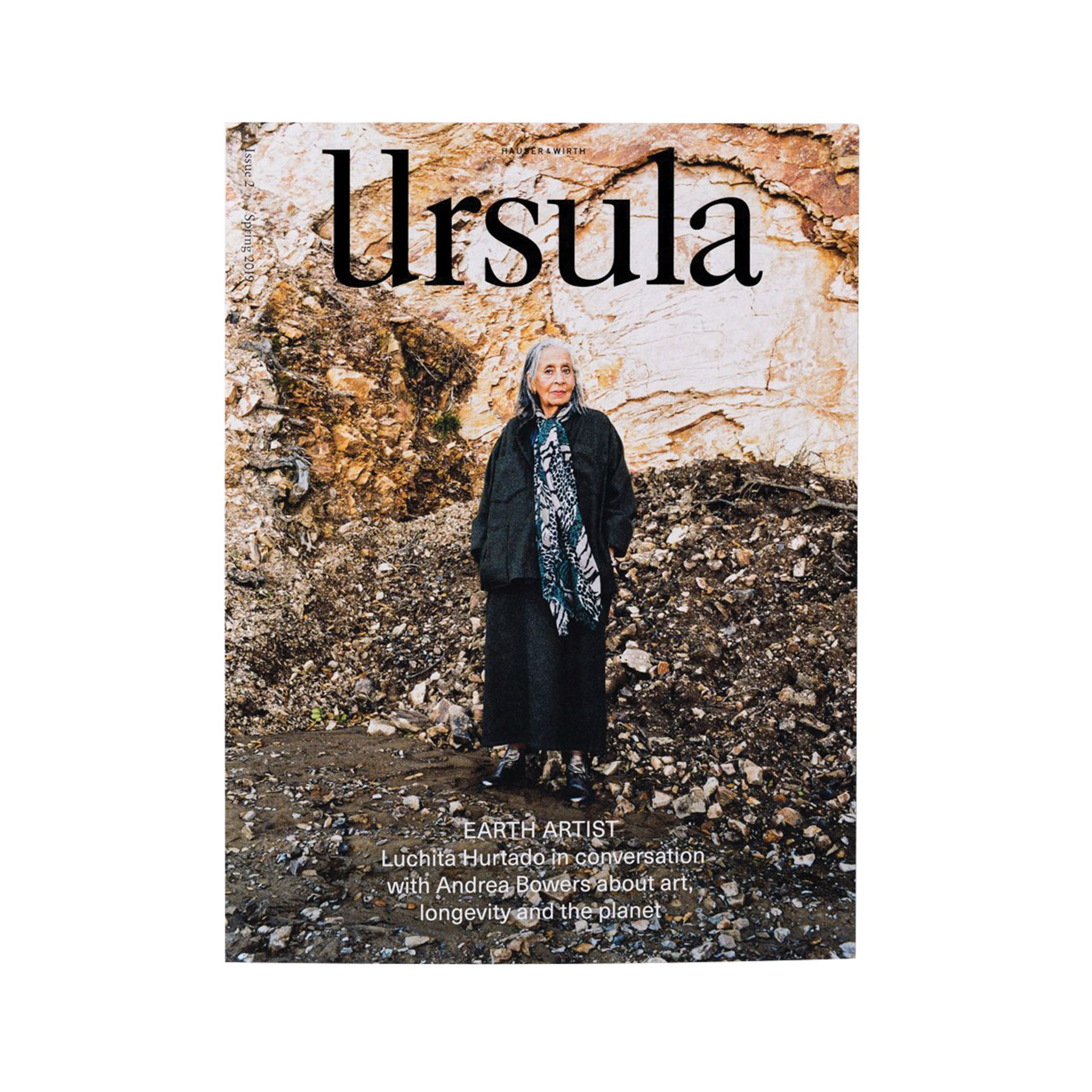

Issue two of Ursula © 2020 Hauser & Wirth Photo: Ed Park.

But in December 2018, the gallery also launched the glossy quarterly magazine Ursula, which is overseen by executive editor Randy Kennedy, who was previously at the New York Times for 23 years. Unterdörfer says that editorial independence is crucial for those who work in galleries’ publishing departments. But they must also have flexibility in terms of what is published. And a vital part of that flexibility, she argues, is how they adapt to a digital future. “The economics are tough—we work in a niche area,” she says, noting that galleries provide generous budgets compared with many publishers. “It’s sad to see the print market change so much, but it’s a good thing to rethink whether print or audio or video is the best medium,” she says.

Another gallery developing new audiences—both on and offline—is Gagosian, which launched its magazine, Gagosian Quarterly, four years ago. “Initially one of our main goals was to present as much context as possible around our artists and exhibitions,” says Alison McDonald, the gallery’s director of publications. “Four years later, our most recent issues have also included more on dance, philanthropy, fashion, film, creative collaborations, poetry, books.”

Issues of Gagosian Quarterly Courtesy Gagosian. Artwork; left to right: © Jonas Wood; © Ellen Gallgher; © Nathaniel Mary Quinn; © Christopher Wool

She notes that the magazine is “expensive to produce” but says her team “are very fortunate to have a loyal base of advertisers who appreciate the level of quality and value of what we are doing”. That allows Gagosian to offer “more content at a lower price point”—$20 per issue or $60 for the year, while the website is completely free.

Potential sales are always a welcome side effect. “If we are doing our job correctly, then the magazine can offer collectors meaningful insights into our artists and their work that might lead to an acquisition,” McDonald says. Unlike Ursula, which is not available online, most articles that appear in Gagosian Quarterly are uploaded to the website. Additionally, the online version of the magazine features videos of specific projects or exhibitions, as well as conversations between artists and other art world figures. The films are gaining traction: over the past 14 months, they have accounted, on average, for 37% of traffic to the online magazine. McDonald says added reach has come from Instagram TV posts of Gagosian’s videos—for example, a Helen Frankenthaler short has had 127,000 views so far. Instead of having a separate profile, content from the magazine feeds into the gallery’s Instagram profile, which has 1.2 million followers.

“Not every cultural initiative needs to be monetisable immediately”.Lucas Zwirner, the moderator of David Zwirner Gallery's podast Dialogues

Perhaps unusually for a sector built on visual images, podcasts are increasingly popular among galleries—Sean Kelly and Lisson Gallery are among those to have taken their expertise to the airwaves. Lucas Zwirner says the gallery launched its podcast because “publishing had a much bigger audience than we anticipated and podcasts were a natural conduit for artists’ voices”.

On Air is a podcast produced by Lisson Gallery Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

He notes that each episode gets between 30,000 and 50,000 listens; the conversation between the artist Jordan Wolfson and the actor and playwright Jeremy O. Harris remains among the most popular. Meanwhile, the podcast is currently at around half a million downloads for seasons one and two. Zwirner is broadening the horizons for season three. “We’re figuring out which conversations would be most interesting to a new generation of art enthusiasts, or even culture enthusiasts,” he says.

So how do these projects play into online selling initiatives? Zwirner notes that the Raoul De Keyser online viewing room during Frieze London in October, which included a video of the younger artist Harold Ancart, led to a real “flurry of activity” in terms of sales.

However, he stresses that “not every cultural initiative needs to be monetisable immediately”. Zwirner adds: “The narrative around galleries is often about size—it’s about how big the top three galleries have gotten, how many artists they’re signing. But instead I think it’s time to really look at what each participant is contributing in a thoughtful way.”