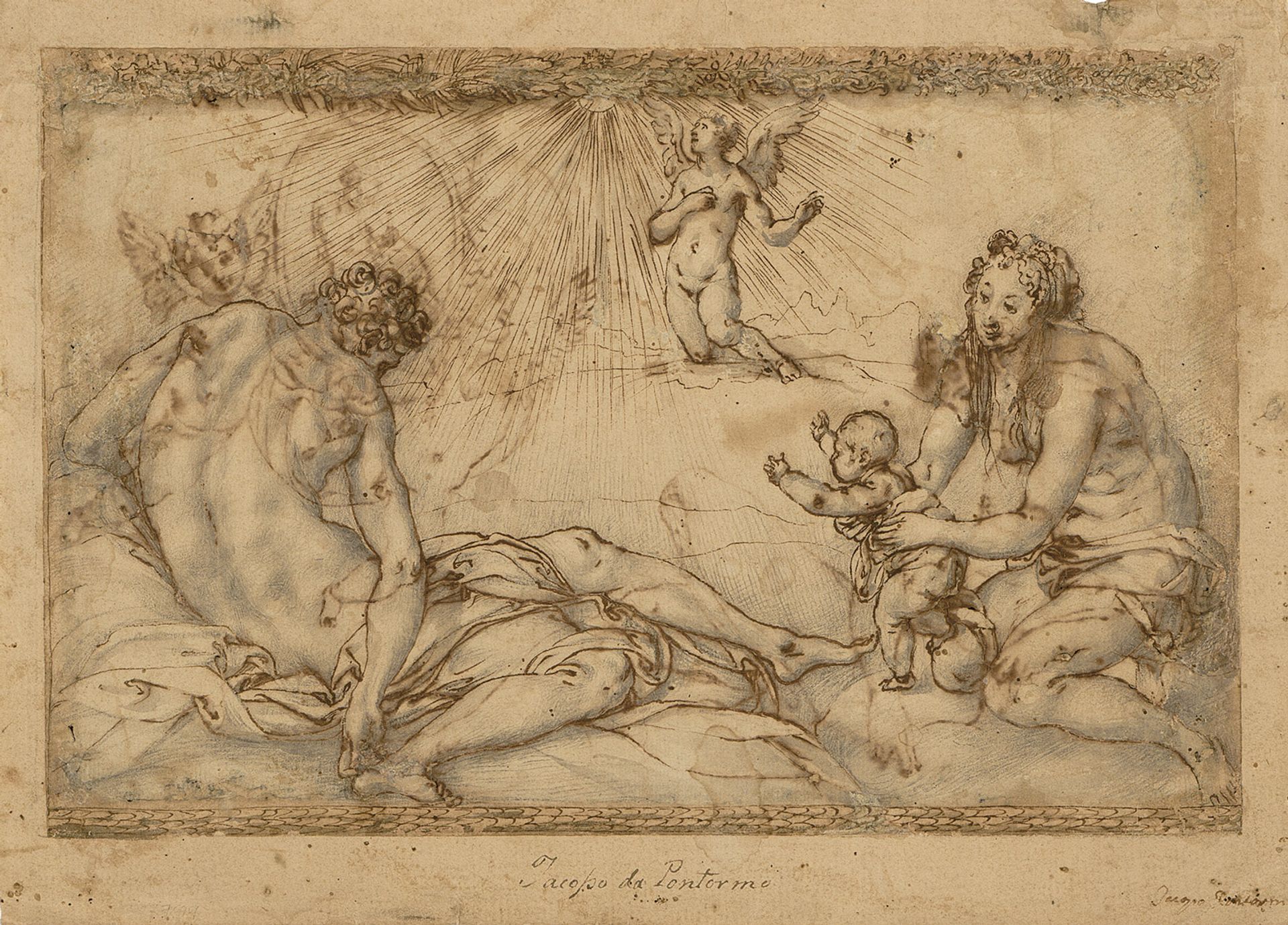

In a bold move, Christopher Bishop Fine Art will anchor its exhibition with just one drawing at the 12th edition of Master Drawings New York (MDNY). The New York-based dealer has spent two years researching a double-sided work that was thought, but not confirmed, to be by the Renaissance painter Jacopo Pontormo. He concluded it is a preparatory drawing for a lost fresco at the Villa di Castello—where Pontormo worked for a period—after determining that it depicts the horoscope of the Florentine patron Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, the villa’s owner.

“This is a rare case where the iconography is the silver bullet of attribution,” Bishop says. Further bolstering his findings, Bishop has established that the early inscriptions on the drawing are from the circle of Vincenzo Borghini, an Italian collector who inherited drawings directly from the collection of his friend, the painter Giorgio Vasari (1511-74).

Bishop is hoping his detective work pays off at MDNY later this month, which takes place at the Academy Mansion and in participating galleries on the Upper East Side (27 January-3 February). The Pontormo’s price will “push over the seven-figure mark”, he says.

Such is the state of the Old Master drawings market today, where new research linking a previously unknown or little-known work to a famous hand can have an exaggerated effect on its value as collectors seek the best works amid an ever diminishing supply.

“Almost any discovery linked to a drawing enhances saleability,” says David Tunick, a New York-based dealer. “If you can, for example, identify a sitter in a portrait or tie a drawing to a painting, these kinds of things invariably add to the value.”

Mercury and Astraea (above) and, on the other side of the paper, Saturn and Ceres, both drawn in around 1537 by Jacopo Pontormo, and on show at Master Drawings New York

For MDNY, Tunick will offer a selection of drawings by Gustav Klimt for the first time to the market. “The original owner, who acquired them in Vienna, kept them in a drawer when his children were growing up because of the subject matter. We kept them in our own drawers from 1987,” Tunick says, adding that the drawings will be included in an addendum to Klimt’s multi-volume catalogue raisonné compiled by Alice Strobl in the 1980s.

Whether newly identified drawings can seal an artist’s overall market value, however, is a matter of debate. “Reattribution happens frequently in the Old Masters sector but less commonly with 19th and 20th-century works, for which provenance information is more readily available,” says Jill Newhouse, an MDNY participant who is showing “a wonderful Degas drawing from an estate”. She says that research has revealed that the sitter is one of Degas’s favourite models, a young dancer named Melinda Darde.

Drawings, which are often works-in-progress, are generally unsigned, making them ripe for re-evaluations but also more problematic in terms of authentication. “If in the case of an Old Masters attribution, there is diversity in the opinion of scholars, this could make confirming the attribution on a new work even more complicated,” Newhouse says.

John Marciari, the associate editor at the scholarly journal Master Drawings, says: “In general, a new discovery that brings a work to the market by a rare master—and thus sets a price for what a drawing by that master is worth today—would probably add value to drawings that have long been known, if only because it establishes a real current price instead of a hypothetical estimate.”

Gregory Rubinstein, Sotheby’s head of Old Master and early British drawings, says that, when it comes to auctions, “our prices are affected by supply; it is difficult to say whether drawings sales cause a quantum shift in the value of an artist”. He adds that auctions of important groups of drawings can have an impact nonetheless.

This month, 28 drawings from the collection of the New York couple Howard and Saretta Barnet—covering some 500 years of history, by artists as varied as Fra Bartolomeo, Parmigianino, Claude Lorrain, and Lucian Freud—go under the hammer at Sotheby’s New York on 31 January. “The Barnet collection could end up redefining prices for several artists,” Rubinstein says.

Bishop, meanwhile, is sanguine about the prospects for his Pontormo drawing. Asked if he would be disappointed if the work fails to sell at MDNY, he says: “It may take people time to get used to the idea, as we’re re-evaluating an entire period of Pontormo’s career. There is a lot of pressure on the top end of the market. In the end, people just want extraordinary things.”