Closing out a week that saw a record price for a painting of any era and pent-up demand in the Impressionist and Modern category, contemporary auctions at Phillips and Sotheby’s in New York reached habitable heights across a broad range of styles and price points—factors most favorable to a continuing strong and stable market.

The double-header evening began Phillips, where the 20th Century and Contemporary Art auction realized a satisfying $113.9m with fees, right in line with last year’s $111.2m on a similar number of lots. Only four of the 43 offerings failed to sell, for a crisp 9% buy-in rate. Five topped $5m, and one lot exceeded $20m, evidence that Phillips’s team of specialists is making pilgrim’s progress in sourcing better property.

Proof of that development was a gorgeous crayon on paper by Pablo Picasso, Portrait de femme endormie. III (1946) from the estate of Anne Marie Aberbach, the widow of Elvis Presley’s music publisher. Estimated to fetch between $1m and $1.5m, it launched a bidding war that finally drew to a close at $8m ($9.3m with fees). Another fabulous work on paper from Aberbach, Henri Matisse’s charcoal Jeune fille dormant a la blouse roumaine (1939) brought $4m ($4.8m with fees; est $1.2m-1.8m).

Courtesy of Phillips

Contemporary lots were not overshadowed completely. New York private dealer Neal Meltzer snagged Christopher Wool’s black-patterned enamel on aluminum Untitled (S134) (1996) for $3.1m ($3.7m with fees). London dealer Inigo Philbrick won Jean-Michel Basquiat’s eerie Untitled (Halloween), dated 1982 and consigned by the Basquiat estate, for a within-estimate $3.5m ($4.2m with fees).

Two artist records were set, for Carmen Herrera and Hélio Oiticia. The cover lot and top earner, Peter Doig’s chilly winter landscape Red House (est $18m-$22m)—inspired in part by an Edvard Munch painting, and looking it—sold to a telephone bidder for $18.5m, $21.1m with fees. The consignor had purchased it at Christie’s London in October 2008 for £1.83m ($3.17m).

Andy Warhol’s still striking 1 Colored Marilyn (reversal series), from 1979, sold to Rochester, New York dealer Barbara Nino of International Art Acquisitions for $1.8m with fees (est $1.5m-2m). “Warhol reversals are hard to find”, said Nino as she exited the salesroom. “It was in good condition, signed by the artist and it was a good buy.”

Courtesy of Phillips

Uptown, Sotheby’s Contemporary Art evening auction (which began while Phillips was still dispatching its last lots) delivered solid, workmanlike results, enlivened by a standout group of 24 works on paper from the Diamonstein-Spielvogel collection that contributed $54.7m of the $310.2m total with fees.

Only three of the 72 lots offered failed to sell, for an impressive buy-in rate of 4%. The tally fell comfortably between pre-sale expectations of $250.5m to $343.5m and represented a 12% increase from November 2016. That said, 44 of the 72 entries were backed by house guarantees, third-party guarantees (defined by Sotheby’s as “irrevocable bids”) or some combination of the two, perhaps indicating a skittish stable of sellers. Another interpretation would be the changing face of the art auction market as trading and collecting morph into a variety of Wall Street-style financial instruments.

The aforementioned and fully guaranteed trove of masterly works on paper kicked off the sale, starting with a precocious Lucian Freud pencil on paper, Boy on the Stairs (1948), which sold to a telephone bidder for $1.2m ($1.45m with fees; est $600,000-$800,000). London dealer Pilar Ordovas, a Freud specialist, was one of the underbidders. “I wonder if it would have sold better in a different context, say in London”, she says. “I thought about getting it for stock because I thought the price was low.” Still, the charming Freud doubled its low estimate.

Another Diamonstein-Spielvogel lot, Jasper Johns’s Untitled (1980; est $800,000-$1.2m), was won by an online bidder for $1.4m at the hammer—a first in an evening sale at Sotheby’s. Most others fell within estimate, though Roy Lichtenstein’s The White Tree (Study), an Edenic scene executed in pencil and colored pencil on paper in 1979, sold to Ed Tang of Sotheby’s Art Agency, Partners for $800,000 ($975,000 with fees; est $450,000-$650,000). Tang also grabbed the artist’s Drawing for ‘Interior with Swimming Pool Painting’ (1992) in the same medium for the same bidder at a final price of $435,000.

Courtesy of Sotheby's

The Lichtenstein streak continued into the various-owners segment with Female Head (1977), which sold to European buyer on the telephone for $21.5m, or $24.5m with fees (est $10m-$15m). The faux Surrealist and Picasso-influenced painting in oil and Magna on canvas is brilliantly composed, with the blonde’s reflection repeated in the Benday dotted mirror behind her. Lucy Mitchell-Innes of New York’s Mitchell-Innes and Nash chased it but did not prevail. “It’s a very good painting, but you can’t get them all,” said the dealer as she rushed out of the salesroom.

Two artist records were set. Laura Owens’s large, richly hued abstraction Untitled (2012), executed in oil, acrylic, flashe, resin, collage and pumice on canvas, raced to a rousing final price of $1,755,000, several times the $300,000 high estimate. The Los Angeles based artist’s mid-career retrospective just opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art, so the timing was opportune for an evening sale debut.

A second artist record followed with the Nigerian born, London-based painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s giant painting The Hours Behind You (2011), depicting five African female figures in white shifts dancing in choreographed motion against a dark background. It sold to another telephone bidder for a thumping $1,575,000 with fees (est $250,000-$350,000). New York dealer Jeffrey Deitch was part of the posse of underbidders.

Courtesy of Sotheby's

David Hammons also had a good night. An iteration of his large, sewn-fabric African American Flag from 1990 brought $1.8m ($2.1m with fees; est $1.5m-$2m), while the sensational mixed-media work on paper featuring a double-sided body print, Untitled (1975), soared above its $350,000 to $450,000 estimate to land at $1.63m with fees, selling to another telephone bidder.

The sale’s biggest-ticket items failed to spark much competition, however. Warhol’s fantastic blue-grounded Mao (1972), executed in silkscreen ink and pencil on canvas was hammered down on a single bid, nudging it into the $30m-$40m estimate range with a final price of $32.4m. Sotheby’s had sold another, equally large version for $47.5m in November 2015. Warhol wizard Jose Mugrabi said as he left the salesroom, “It was a fair price for a good painting, and I think a very good buy.” Pressed to comment on that precipitous drop, Mugrabi maintained his trader’s wits, adding only, “The price of today is a fair price.”

Basquiat’s market has wobbled slightly since the $110.5m record price set at Sotheby’s last May. Here, his steer-horned Cabra (1981-82)—partly inspired by Muhammad Ali’s early upset victory over boxing champ Oscar “the Bull” Bonavena—fetched $9.5m ($10.95m with fees; est $9m-$12m). The dealer Tony Shafrazi exhibited the work in 1983, and it was purchased from him in 1993 by Yoko Ono, who lent it to the Beyeler Foundation’s Basquiat retrospective in 2010-11.

Courtesy of Sotheby's

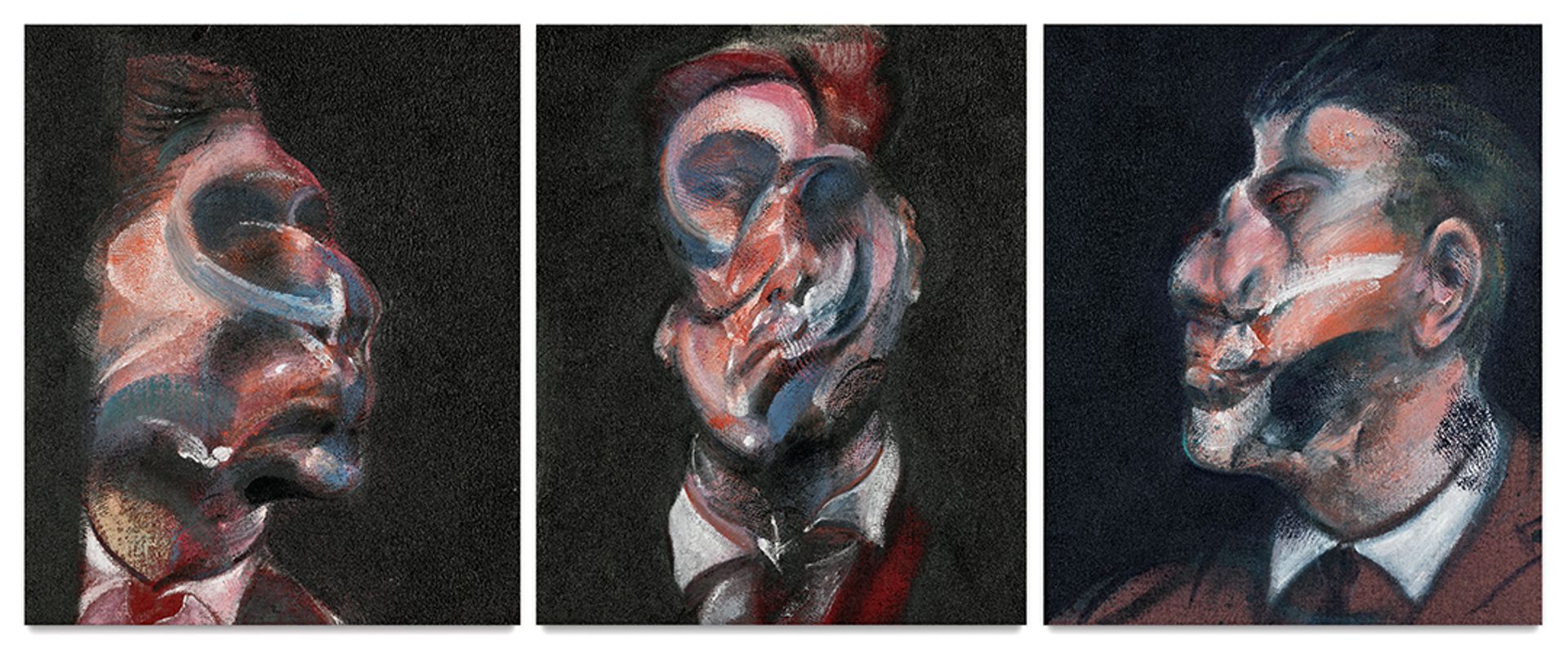

The second and slightly larger of Louise Bourgeois’s bronze spiders to be offered this week, Spider IV (1997; est $10m-$15m), sold to a telephone bidder from Asia for $12.8m, or $14.8m with fees, beating out Amy Cappellazzo’s phone bidder. The Sotheby’s Spider was backed by a house guarantee. So too was the evening's top lot: Francis Bacon’s searing triptych Three Studies of George Dyer (1966), which sold on a single telephone bid for $35.5m, $38.6m with fees (est $35m-$45m). Luckily for the seller, it was backed by an irrevocable bid as well as the house.

Though Sotheby’s didn’t copy its archrival with an Old Master offering, the auction house did include in its sale Michael Schumacher’s Grand Prix winning, Formula I racing Ferrari from 2001 (est $4m-$5.5m), which kicked off a tug-of-war that pushed the final price to $7.5m. In the middle of the monotonous telephone battle for the F2001, legendary contemporary art prospectors Mera and Don Rubell looked at each other in seeming disbelief, stood up in tandem and exited the salesroom.

The takeaway at both Phillips and Sotheby’s is that the contemporary art market is finely race-tuned but obeying most speed limits—for the moment.