Only 12 paintings have sold for over $100m at auction. Last night at Christie’s, a work by the Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci not only joined that club but rocketed past the previous mark, notched by Pablo Picasso’s Les femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’), which made $179.3m at Christie’s New York in May 2015.

After the gasp-inducing contest had narrowed to two bidders, the 500-year-old painting titled Salvator Mundi sold to an anonymous telephone bidder on the phone with the auction house’s worldwide co-chair of postwar and contemporary art, Alexander Rotter, for a record-obliterating $400m at the hammer, or $450.3m with fees. (In number-crunching shock and awe, the buyer’s premium, if Christie’s gets to keep it all—which is doubtful—amounts to $50,312,500.)

That price propelled the auction’s total to $758.9m with fees, well beyond pre-sale expectations of $410m to $486.2m. It dwarfed last November’s $276.9m tally on a comparable number of lots, a quantum leap of 184%.

Though hardly relevant in the context of Leonardo’s last painting of the saviour of the world, all but five of the lots that sold made over a $1m, and of those, nine made over $10m. Nine of the 58 lots offered failed to sell, for a decent buy-in rate by lot of 16 percent.

Beyond the Leonardo, five artist records were set, including for Vija Celmins, whose “Lead Sea #2 (1969) made $3.5m ($4.2m with fees) and Lee Krasner, whose spectacular oil and paper collage on Masonite, Shattered Light (1954), fetched $5.5m.

Christie's Images LTD 2017

The evening got off to a sizzling start with Adam Pendleton’s Black Dada (K) (2012) going for $225,000 (est $40,000-$60,000) in his auction debut, followed by Philippe Parreno’s balloon armada of tropical creatures, My Room is Another Fish Bowl (2016), which floated to a record $516,500 (est $250,000-$350,000). Los Angeles dealer Stavros Merjos was the underbidder on the red-hot Pendleton.

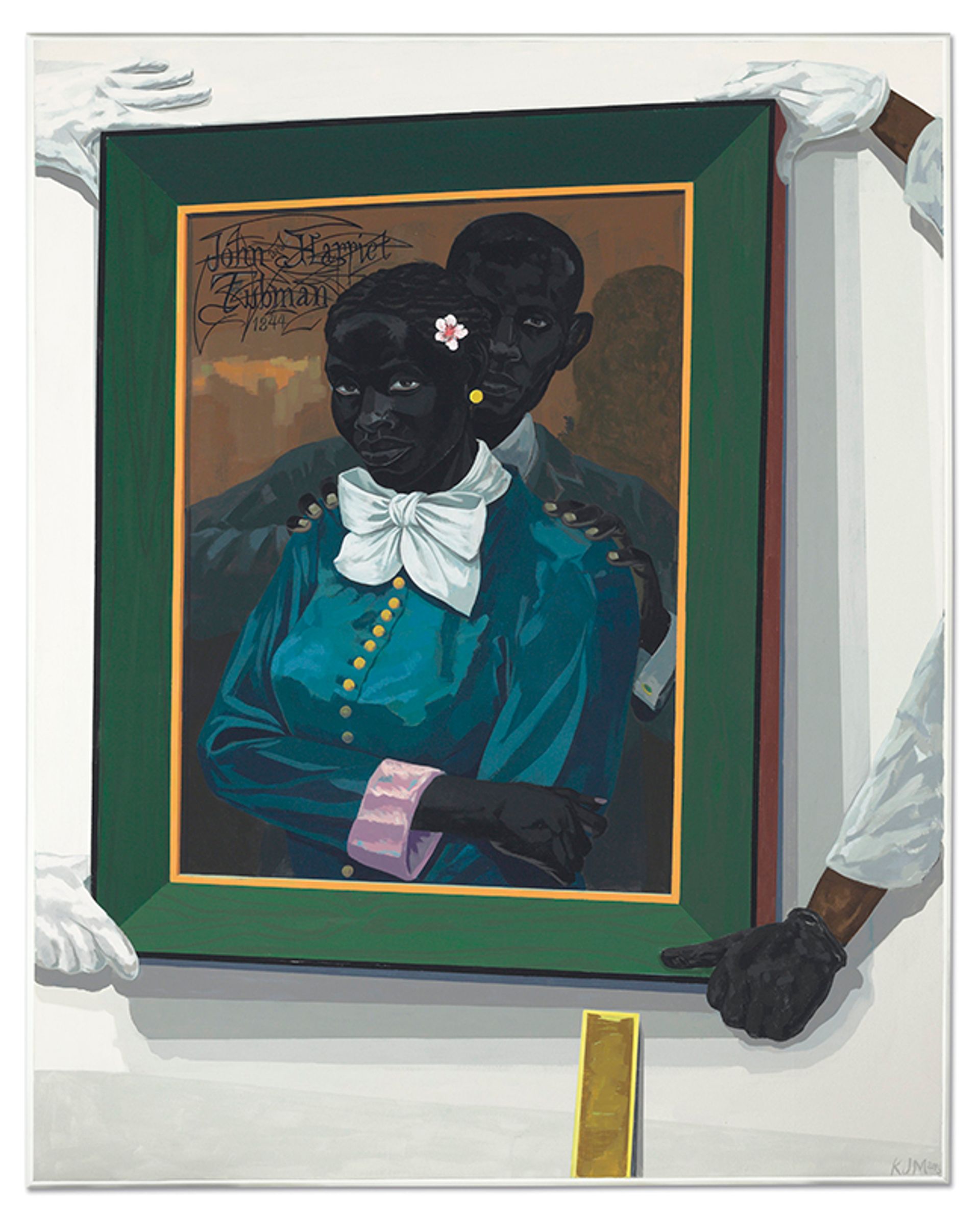

The atmosphere in the jam-packed Rockefeller Center saleroom just as quickly turned serious with Kerry James Marshall’s masterful Still Life with Wedding Portrait from 2015 (est. $1m-1.5m), featuring the Abolitionist couple John and Harriet Tubman and included in the artist’s recent, critically acclaimed traveling retrospective. It attracted 15 bidders, according to head of sale Sara Friedlander, and sold for $4.2m at the hammer, a record final price of $5,037,500.

Price points quickly escalated a few lots later, when a phone bidder with Andy Massad nabbed Mark Rothko’s glowing and aptly titled oil on canvas Saffron (1957). Included in the artist’s major posthumous retrospective in 1978, and landed at a mid-estimate $28.5m at the hammer ($32.4m with fees). It last sold at auction at Sotheby’s London in June 1991 for £770,000 ($1.25m).

Christie's Images LTD 2017

In that same rarified Abstract Expressionist vein, Franz Kline’s Light Mechanic (1960), anchored by a brawny black structure, sold to another telephone bidder for $18m at the hammer, nailing the unpublished estimate of $20m once fees were factored in. Hans Hoffmann’s thickly impastoed and vibrantly coloured Lava, also from 1960, flowed to an artist record $8,862,500 (est. $4m-6m). Both hailed from the collection of Heinz and Ruthe Eppler, which contributed $71.4m to the evening’s total.

Still, it was hard to focus on anything except for the dusky yet radiant, 800-pound gorilla in the room, the oil on walnut panel, Salvator Mundi (around 1500), which had its debut as a freshly authenticated Leonardo at London’s National Gallery in the 2011-12 exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan.

The abraded and heavily restored painting, featuring a richly robed Christ holding a glass orb in his left hand and making a gesture of benediction with his uplifted right hand, was snatched from obscurity in 2005 when Alexander Parish, a sharp-eyed Old Master dealer, spotted it in a regional auction in the US and bought it for under $10,000. At the time, it carried no attribution to Leonardo.

Christie's Images LTD 2017

That sale wasn’t listed in Christie’s 20-page-long catalogue entry—nor, for that matter, was Russian oligarch Dimitry Rybolovlev, who acquired it in 2013 for a reported $127.5m, shortly after Sotheby’s brokered the sale from Parish and cohort of dealers for $80m. A June 1958 auction at Sotheby’s London was duly noted in the catalogue, when the work sold for £45 under an attribution of Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, an artist who worked in the studio of Leonardo.

This time, the unpublished estimate was in the region of $100m, and the lot was backed by a third party. Tonight it fetched a record-smashing, and worth repeating, $450.3m.

Bidding opened at $70m and dutifully chugged along at $5m increments until the auctioneer and Christie’s global president Jussi Pylkkänen informed the room, “I can sell it at $90 million,” a perfectly timed remark that seemed to launch a bidding war among three dueling telephone bidders. It was a madcap, 19-minute performance piece, with three evidently deep-pocketed challengers playing the numbers, jumping at times in $10m spurts or deaccelerating to measly $2m increments.

When the numbers game reached an astonishing $370m, Rotter, competing against his co-chair Loic Gouzer and Old Master department head Francois de Poortere, fairly shouted “400!”—a $30m leap that sealed the deal.

Christie's Images LTD

“It was unbelievable,” Rotter said after the sale. “I tried to look casual up there but it was very nerve-wracking. All I can say is, the buyer really wanted the painting and it was very adrenaline driven.”

Buttonholed as he exited the salesroom immediately after the marathon bidding war, dealer Robert Simon, who orchestrated the authentication of the Leonardo and made the earlier deal with Sotheby’s, said, jokingly at first, “I think it was cheap.” Asked what he thought the picture would make, Simon says, “the number in my head was $280m, but I’m thrilled to see the number of bidders and how powerful an impression the picture was received. I feel like a proud father....I hope it goes to a public institution or a place where it will be seen.”

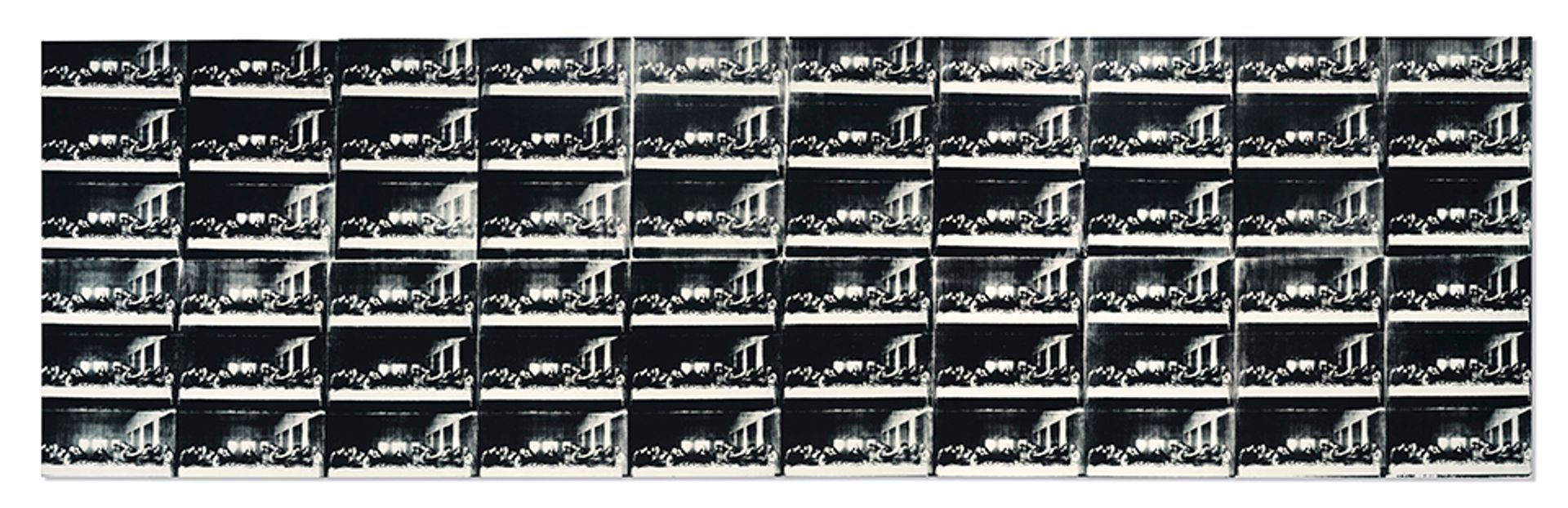

One could endlessly debate the reasoning behind placing an Old Master painting in a contemporary art auction, but suffice it to say the move to sell “the last Leonardo” was pure marketing genius. Its corollary, Andy Warhol’s gloomy, wall-hogging homage, Sixty Last Suppers (1986), hammered down at $56m ($60.9m with fees) to another anonymous telephone bidder, within the unpublished estimate in the region of $50m.

Christie's Images LTD 2017

Nearly lost in the shuffle was Jean-Michel Basquiat’s gold-toned, teeth bared Il Duce, painted in 1982 during the artist’s second trip to Italy, which flopped under a $25m to $35m estimate. That was bad news for Christie’s since it had guaranteed the work, probably at the low end of the estimate, meaning the house lost half of the premium gain made from the Leonardo.

Another heavy hitter in the tumultuous and almost hallucinogenic evening included Cy Twombly’s billboard-scaled cover lot, Untitled (2005), covered in huge, vermillion swirls. It sold to another anonymous telephone bidder for $46.4m with fees (unpublished estimate in the region of $40m).

In a more playful realm that felt good after all the bidding drama, Philip Guston’s crowded snack table, Summer Kitchen Still Life (1978-79, est $5m-$7m), groaning under the weight of the artist’s signature fetishes, including a wristwatch, alarm clock, salami sandwich and coffee mug, sold for $5.6m ($6.6m with fees). It last sold at Christie’s New York in November 1991 during that earlier art-market slump for $187,000—still more proof that escalation seems inevitable.