A series of bitter court battles taking place in New York focus on the fraught issue of buyers defaulting on their art purchases. The cases centre on one art dealer, Anatole Shagalov, and his company Nature Morte (no connection to the Delhi gallery), who is being sued by Sotheby’s and Phillips auction houses. Art loan companies and major galleries—including Paul Kasmin and, according to court papers, David Zwirner—have also been pulled into the fray. They are just the visible part of a complex web of accounts of art being used as collateral for loans, and, allegedly, over-leveraging, defaulting on payment and attempts to shelter assets from creditors.

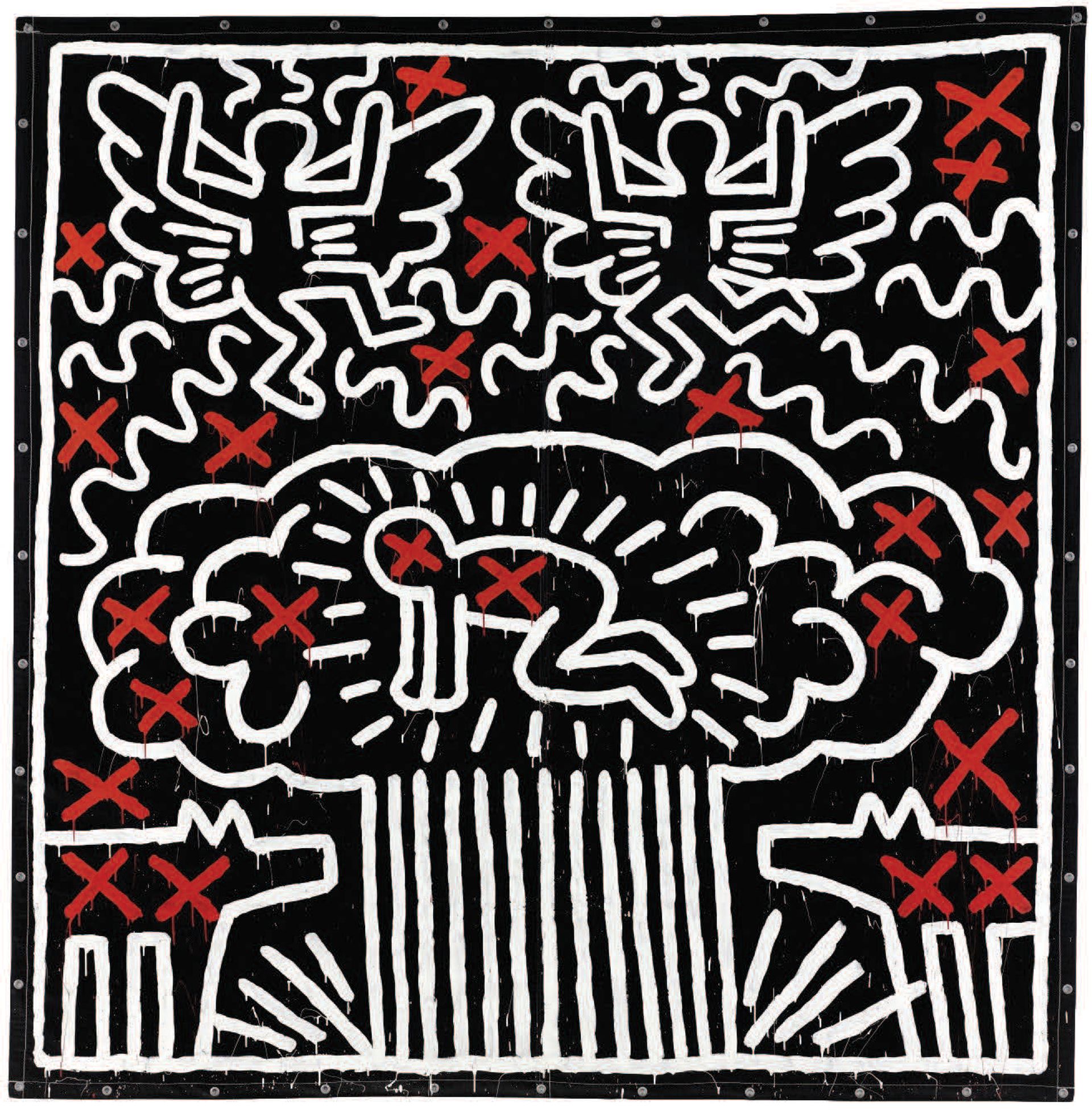

In the cases of the auction houses, Sotheby’s is suing Shagalov after he placed the winning bid of $6.5m on an untitled Keith Haring painting from 1982 in May 2017 in New York—a record price for the artist. After several reminders and, it says, no sign of payment from Shagalov, the auction house resold the work to another client for $4.4m and sued Shagalov for the difference.

Shagalov claims that Sotheby’s agreed to let him pay in instalments, and his lawyer, Mathew Hoffman, says the firm did not make a “commercially reasonable” effort to get a higher price. By way of proof, Shagalov says the Madrid-based art adviser Marco Mercanti was willing to pay $5m for the Haring. John Cahill, Sotheby’s lawyer, denies that Shagalov was given such payment terms and questions whether Mercanti was aware that the painting was subject to an ongoing court case. Sotheby’s also contends that Shagalov falsified documents relating to Mercanti’s offer, which the dealer vigorously denies.

Hoffman says that he cannot disclose the heart of his defence because certain documents have been sealed by Sotheby’s. But, an auction house spokeswoman says: “All of the documents have been produced with client’s names redacted. However, Shagalov’s attorneys can also see the details confidentially, un-redacted. There is nothing keeping them from making their argument publicly and they have done so.”

Keith Haring’s Untitled (1982) was sold for $6.5m at Sotheby’s in May 2017 but was never paid for The Keith Haring Foundation via Sotheby’s

Attempt to hide assets

In a comparable case, Phillips is suing Shagalov for defaulting on the purchase of Morris Louis’s Para IV (1959) and Christopher Wool’s Untitled (P271) (1997) at auction on 8 November 2015, for a total of just under $6m. Shagalov argues that he was deliberately misled into bidding on and buying these works, and should therefore be absolved of any responsibility for his purchases. The auction house did not wish to comment further on the case, which is ongoing.

Sotheby’s is also accusing Shagalov of attempting to hide his assets following legal action, by signing over $10m-worth of art for $6.9m to the art loan company AOI, which was co-founded by Christopher Krecke, formerly of the art finance company Art Capital. According to court papers, AOI was prohibited from selling the art, but days later John Cahill, Sotheby’s lawyer, says he discovered two of the works were for sale at Barbara Gladstone Gallery, which declined to comment except to say “it is not party to any litigation”. AOI did not respond to requests for comment.

Shagalov’s lawyer Mathew Hoffman says that the AOI deal was an “ordinary repo [or repurchase] transaction”. He describes his client’s business model as: “He borrows money, he buys art. He tries to sell it at higher prices. He borrows more money using that art, he tries to sell it at higher prices.”

But in a hearing on 9 January in the Sotheby’s case, Judge Charles Ramos described art deals, in general, as anything but ordinary. “I have never seen an industry more ripe with fraud and misconduct than the art business,” he said. “To say there’s such a thing as artistic ethics is an oxymoron. Most of the cases I’ve had involving art dealers involve fraud outright. Just plain old fraud. This is not a nice business…I’ve seen brokers sell the same work of art three times and a work of art they didn’t own.”

According to another lawsuit, Shagalov is also in dispute with the former corporate raider turned gallerist Asher Edelman, whose company Artemus operates a model whereby it buys an art work for about 50% of its retail value and leases it back to the owner—a form of “art lending”. In this instance, Shagalov is suing Edelman, to whom he had sold a portfolio of works, after Edelman sold some of them to recuperate unpaid lease fees. Shagalov contests his right to do this—and in so doing, challenges the very basis of a sale/leaseback arrangement—claiming that the works were collateral for a loan, and therefore not Edelman’s to sell.

In a counterclaim, Edelman says he took this step after he discovered that Shagalov had sold him a Frank Stella work that he did not fully own; Edelman says it was partly owned by Paul Kasmin gallery. Edelman contends that Shagalov disguised the fact that the Stella was partly owned by the gallery by falsifying a new invoice, but Hoffman says: “Mr Shagalov categorically denies giving Edelman any fraudulent documents”. In addition, Edelman claims in court papers that Shagalov is also in default to the David Zwirner gallery. Zwirner declined to comment and Kasmin did not respond to our queries. Hoffman says there has been no litigation brought by Zwirner and so he cannot comment.

While these cases concern a single individual, allegations of defaulting are not uncommon. In another action, Sotheby’s is suing a client, named as Eugenio Paolo Losa, for $8.25m for two works bought at auction in November 2017. At the time of writing, Losa had not responded to this claim and the next hearing is scheduled for 9 March.

Art as collateral

Then, in a case apparently unconnected to Shagalov, Paul Kasmin gallery is being sued by another art loan company, Emigrant Bank Fine Art Finance, for more than $35,000. The loan firm alleges Kasmin defaulted on “success fees” payable when a work is sold. Emigrant has provided Kasmin with various loans since 2007, according to court papers. Kasmin and Emigrant’s lawyer did not respond to requests for comment.

The art adviser Todd Levin says getting a loan using art as collateral is becoming increasingly common because the market is so inflated. “When the market is this frothy it encourages people who normally would circle around the fringe to dive more directly into the centre. These activities are not illegal but they are questionable from a purely business perspective,” he says. Andrea Danese of Athena Art Finance says: “These problems are far more frequent than people realise, but often resolved behind closed doors. And, often, what’s on the surface is not the whole story: auction houses rarely sue and generally there is a bigger story behind [the action],” he says. Danese adds that art galleries and dealers, with their sporadic cash flows, are sometimes tempted to go to multiple lenders, ending up over-leveraged.

Vendors have sometimes been too trusting. Danese says: “The auction houses shouldn’t let people bid until after they have checked they can honour their obligations. But they want to seal the deal and they hope for the best.”