The Centre Pompidou in Paris is a fitting venue for the latest survey of the artist Mona Hatoum. It was there that the curator Christine Van Assche gave the Lebanese-born, London-based artist her first solo museum show in 1994. The exhibition that opens today (24 June-28 September), is also organised by Van Assche, now the Pompidou’s chief curator. It brings together more than 100 works ranging from the little-known “minimalist” works on paper of the 1970s to a major new commission, Map (clear) (2014), and is due to travel to Tate Modern in London and Kiasma in Helsinki in 2016. In an interview with our sister newspaper, Il Giornale dell’Arte, Hatoum looks back on her daring early performances, her openness to working in different media and her map works reflecting global conflict.

The Art Newspaper: The Centre Pompidou has showed real loyalty to your work over the years. What does this survey mean to you?

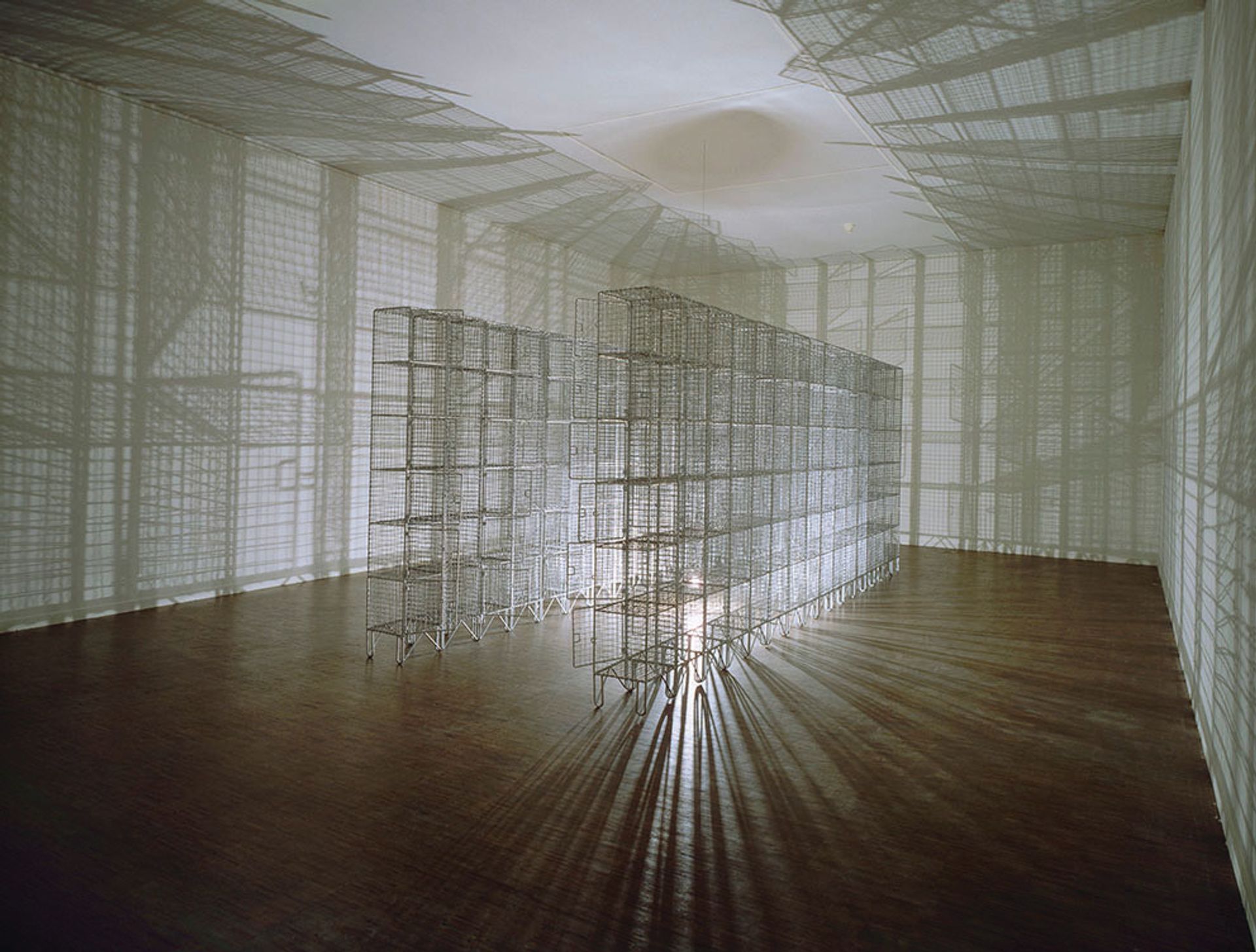

Mona Hatoum: It is wonderful to have this kind of support from a museum. It was great when I was offered a solo exhibition in the Galerie Sud in 1994, which is over 20 years ago now. It was my very first solo show in a museum anywhere in the world and it helped put my name on the map. It was also one of the reasons I was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in London the following year. This was all thanks to Christine Van Assche who came across my work at the Western Front Art Centre in Vancouver. She invited me to propose a video to be produced by the Pompidou. Corps étranger, the installation that takes you on a journey inside my own body, was subsequently acquired by the Pompidou and I was offered a solo exhibition in which this commissioned work was shown for the first time along with two other large installations: Light Sentence and The Light at the End.

For this exhibition, you had to look back at all of your artistic work. What do you think about your earlier works today?

It is always hard to look back at works you made decades earlier. When I look at the very early performance work I created in the 1980s, I am amazed how daring some of these performances were and how fearless I used to be. It was totally the right medium for me to use at the time. But there was an explicit content and narrative element in those works, which is something I no longer ascribe to. I don’t like to hit people over the head with a message anymore. I prefer to articulate my ideas in more subtle ways through the abstract and formal qualities of the work.

The early installation works still resonate with me and, in some cases, seeing them again makes me wonder why I did not expand on those concepts at the time. It makes me feel like revisiting some of those ideas and creating more works along those lines. I feel the same about the series of long forgotten works on paper I made in the 1970s, when I was still a student and at the height of my “minimal phase”. I am happy to be exhibiting them here for the first time as I see connections between them and the later sculpture and installation works.

You have also created a new work, Map (clear). Could you tell me more about it?

This work developed out of a series of floor works from the mid-1990s where I was trying to destabilise the surface of the ground you are walking on. With Map (clear) I expanded this idea of “shaky ground” to include the entire world. There are no political borders here, only the continents depicted in transparent glass marbles lying precariously on the floor. The marbles roll around and get easily knocked out of place whenever people walk across the space, making it very unstable. The surface of this map is both fragile and also threatening to those who approach it as it makes the floor surface treacherous for the viewer who can easily slip and fall.

What does your map of the world look like today?

In 2006 I made a work called Hot Spot. It’s a globe made of steel rods with red neon delineating the contours of the continents on its surface. This work implied that the whole world is a political hot spot caught up in war, conflict and unrest—that war and conflict are not restricted to certain areas but something that affects the world as a whole. This is still the way I would portray the map of the world today.

You have used many different materials and techniques in your work. What is left to explore?

The aim of my work is not simply to explore materials and techniques. There are recurring themes and concepts that can manifest themselves in many different forms. It is true that I have stayed open to exploring different ways of working. On one hand, I like the handmade and using various crafts and I like to be occupied making things myself on a daily basis. On the other hand, I like industrial things and fabricated structures that make reference to architecture. I also like to use found objects and pieces of furniture that I transform in some way. I go with whatever attracts me or resonates with me at any particular moment, and what I feel is most suitable for a particular space. The space I am developing an exhibition for, its specific characteristics and history, is often the starting point and the inspiration for the works.

I often say that what I like most about being an artist is that I never know where in the world the next exhibition is going to take me, what will inspire me about that particular location, what materials or crafts I will find and what I will end up making. So as long as I am invited to show my work in different spaces somewh ere in the world, there will be new and exciting things to explore.

Interview by Luana De Micco with additional reporting by Hannah McGivern