She only graduated from the Royal Academy Schools just over a decade ago, but the intense figurative oil paintings of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye have already won the London-based artist international acclaim. Executed in a rich, dark palette and peopled with enigmatic and predominantly black characters conjured from her imagination, the paintings have been described by Okwui Enwezor, the director of this year’s Venice Biennale, as “post-portraits”. They are usually completed in a single day. Although Yiadom-Boakye has said that “race is something that I can completely manipulate or reinvent or use as I want to… the complexity of this is an essential part of my work”, she is also adamant that “my starting point is always the language of painting itself and how that relates to the subject matter”.

Yiadom-Boakye won the Victor Pinchuk Foundation’s Future Generation Art Prize in 2012 and was nominated for the Tate’s Turner Prize in 2013. She has had shows at institutions including London’s Chisenhale Gallery and the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York. A solo exhibition at Munich’s Haus Der Kunst, where Enwezor is the director, is due to open in October. Yiadom-Boakye spoke to The Art Newspaper in her east London studio as she prepared for her major survey show at London’s Serpentine Gallery, which opens this month.

The Art Newspaper: You’ve turned down the psychological thermostat since showing your big, scary, lairy painted ladies in Bloomberg New Contemporaries more than 10 years ago, but your figures still demand an active and dynamic engagement with the viewer.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: That emphasis on a strong presence is really important, and I’m always looking for a strong line, a strong curve or a strong look. They should never appear to shrink away—they are never victims, never passive. I always destroy the work if anyone looks passive.

What was it about painting that made you take it up and stick with it?

Number one, it’s the engagement that I have with painting, and how it makes me feel when I do it and also when I look at it—though not so much at my own work, but other people’s work. Then there’s the physicality of it: there’s something very particular to oil painting, especially. It’s just very dirty, it’s very messy; it doesn’t always do what you want it to do, it’s alive, it doesn’t dry very quickly. It’s fleshy and unpredictable—it has a kind of human quality to it.

Your work has a complex relationship with portraiture. Although you make many references to specific historical works of art, the figures you paint are not real people but are invented, having been drawn from a range of sources. What made you choose this way of working?

For a long time now, I haven’t thought of what I do as portraits—I see them more as figurative paintings. I realised quite early on that I was not so interested in painting people whom I knew or doing the classic portrait from life, although I did it a lot when I was younger, because to be able to improvise, it’s important to train yourself how to look, and to be aware of how a body is composed or how a face sits. But once I tried to paint this guy who was really an incredible character and I was so disappointed with the outcome: I didn’t capture anything of him. Then I realised that I wasn’t interested so much in trying to capture someone who was actually there as I was in just the painting itself, and in letting that lead and decide what a person’s facial expression does, where a hand sits or what a gesture is. So I was much more drawn to that as a way of working, to work from a composite of drawings, scrapbooks, found images, photographs—anything—and to bring it all together so it would be exactly what I wanted it to be: to play God.

You’ve said that you want “to drag the figures out of the paint”.

Yes, it is like that. I used to struggle so much more when I thought too hard about the figure and the ground being two separate things, but as soon as I realised that they were one and the same, it was so liberating, because you’re then handling the whole thing as a painting. It’s not a person, it’s not a portrait; it’s a painting, and everything that goes on within it qualifies the other elements. It is all linked in with the stuff of how they are actually composed and how they come about: the colour that comes from underneath, the layer that builds up, the way the colours work together, the way a mark sits. Just going back to following the line of the figure, what the muscle is doing, what the physicality of the thing is, actually trying to transcribe that in paint becomes part and parcel of the meaning of it.

Virtually all your characters are black, which brings in a whole raft of considerations around race and the representation of black people in art history. But although the presence of these figures in large-scale oil paintings undoubtedly carries a political dimension, this sits alongside a multitude of readings and entry points.

It always stuns and worries me when people say, “Oh, but you’re not political”, because I am. It’s just that there are many ways to skin a cat, and it’s so easy to latch onto something and just bang on about it. I never thought that there was only one way to say something or to be something. I’ve never found black people exotic because I grew up with them and that’s just normal to me. If I wanted to be really strange or to exoticise, then the figures in my paintings would be white—but then again, some of them are white.

Even though you deliberately keep details of clothing and surrounding “props” to a minimum, your figures vary greatly in appearance and colour.

I’ve never really seen them as being particularly one thing or another, because there are so many different tones within them and the colours dictate so much of what they become. Often, it’s ambiguous, and they could really be anything—with some of them, you can’t even tell if they are men or women, while with others, you definitely can. My mind is always slightly on other things when I’m making them, so I guess part of me forgot that they were black a long time ago, in the same way that I don’t wake up and think of myself as being one thing or another. It’s not something that you necessarily think about all the time, but it’s there.

Each painting is made in one session in a single day. Why did you set yourself such a constraining framework?

Rendering something in a day was always a practical measure, because if you try to go back to oil paint overnight, the surface just doesn’t work. It dries at different times and you’ve already got a skin on it. I also realised that it didn’t necessarily improve anything; sometimes your first decision is the right one and you need to go with that. The more I pontificate on the canvas, the more it goes wrong. Maybe that’s to do with how I feel about human nature in general: I think people know what they mean, it’s just whether or not they are prepared to accept it and just do it rather than fuss and go around it. It also quite frequently goes wrong and there’s a lot that I junk, but that’s also part of it.

All of your works have titles, some of which can seem quite cryptic. What is their relationship to the paintings?

We think in pictures but a lot of the time we also think in words, and I love to use language. Occasionally the titles describe what’s going on or suggest it, but in a very oblique way. Then, a lot of the time, they are associations I made while I was doing something and are completely meaningless to everyone else. But I like them to have a beauty of their own that doesn’t necessarily describe something specific. With paintings, as with many things that you experience through looking, sometimes you can’t really describe things but you know how they make you feel, and it can be quite overwhelming and powerful. So maybe the painting and the title can sometimes work together to make you react in an unexpected way.

The title of the Serpentine show is Verses After Dusk, and you’ve described your paintings as “snippets”, part of a larger unfolding narrative, in which one work never says it all, but leads on to others.

When I write, I always have trouble structuring stories to enable me to finish in the way that I want to, and with painting, there’s often a sense that I can never really get everything I wanted into one work. Occasionally I do, but usually once that one thing is captured, then I’m thinking, “OK, well, I got this, but I didn’t get that”, so that carries over into the next thing. The narrative is never straightforward, but the one thing that drives it is the actual process of making the painting. In each painting, there is something I am trying to learn, or trying to do or to get to—and I’m not there yet.

• Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Serpentine Gallery, London, 2 June-13 September; www.serpentinegalleries.org

Digest: Lynette Yiadom-Boakye Background

Born: London, 1977

Education: Born in London to Ghanaian parents, Yiadom-Boakye has “a typical British art education”, as she describes it, starting with a foundation course at Central St Martins in London before a “more liberating” BA at Falmouth College of Art, Cornwall, between 1997 and 2000. She then returns to London, graduating from the Royal Academy Schools with an MA in 2003.

Milestones: Her startlingly powerful paintings of grimacing women attract wide attention when she is selected for Bloomberg New Contemporaries and exhibited in the John Moores Painting Prize in 2003; Charles Saatchi is among the collectors who buy her work. Solo exhibitions at the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York (2010), and the Chisenhale Gallery, London (2012), follow. She is awarded the 2012 Future Generation Art Prize by the Victor Pinchuk Foundation and receives a solo show at the Pinchuk Art Centre in Kiev, Ukraine. In 2013, she occupies an entire gallery in Massimiliano Gioni’s exhibition The Encyclopaedic Palace at the Venice Biennale, and is shortlisted for the Tate’s Turner Prize.

Lives and works: London

Represented by: Corvi Mora, London; Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Key works

Bound Over to Keep the Faith (2012)

This large-scale and somewhat sinister man, wearing a loose white shirt and leering smile, has been a regular presence in Yiadom-Boakye’s work for the past few years, and often ushers in a new series of paintings. He tends to be painted (but not necessarily exhibited) in pairs, and is one of a wider cast of recognisable characters who recur in the artist’s paintings, wearing the same clothes but with subtle shifts in pose and expression. “When I start a body of work, I will do these two paintings, and each time there will be a slight variation, but essentially it’s the same man,” she says. “They are an anchoring of how I think generally and a reminder of where I am. It is also the sense of getting to know someone better. They have changed a lot since their first incarnations.”

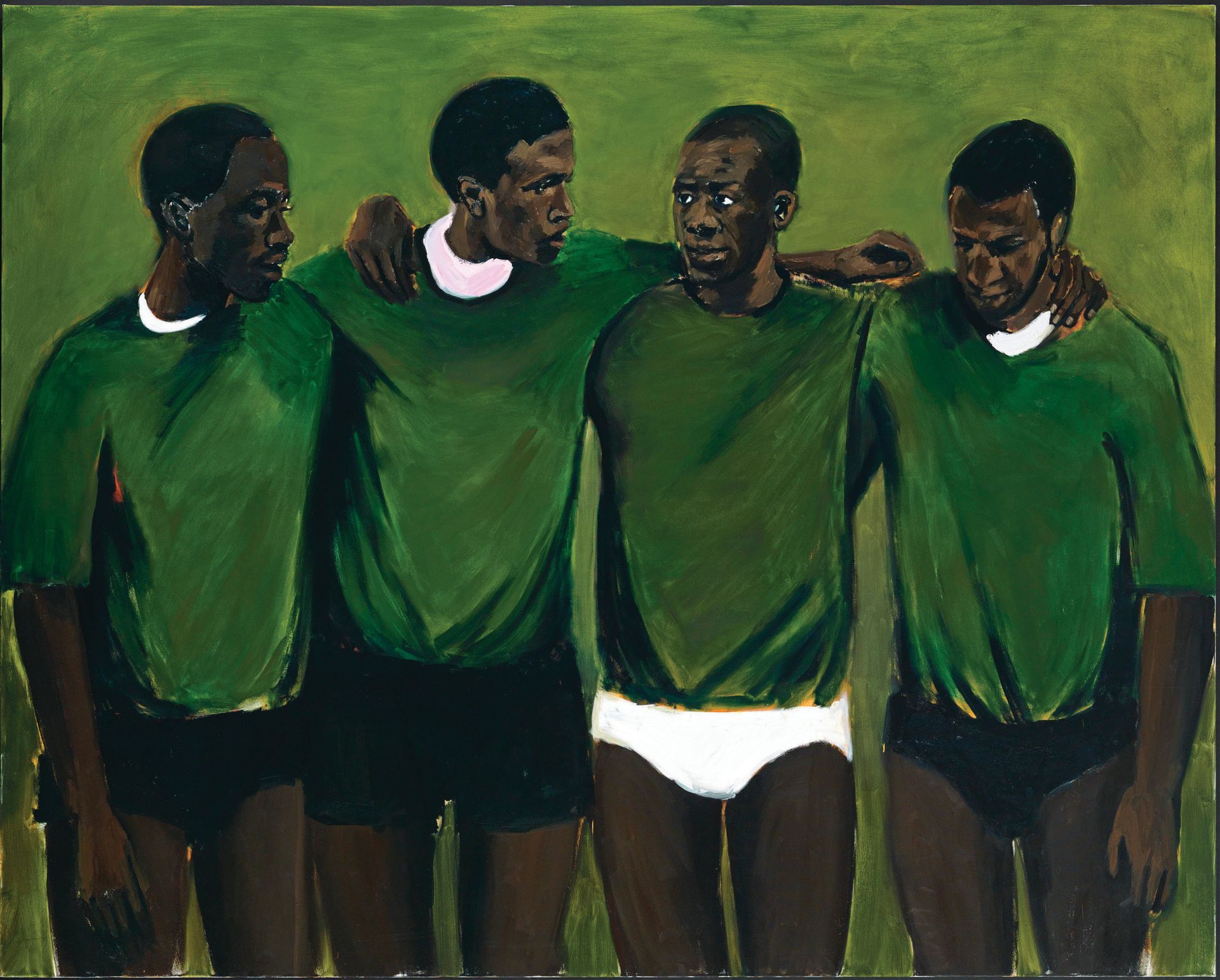

Complication (2013)

Four men wearing what looks like sports kit stand in a row, as if posing for a team photo. Enigmatic but evocative groups of figures form a significant strand in Yiadom-Boakye’s work. As with her single characters, any particulars of who they are or where they might be are kept to a minimum—here, it is not even clear whether they are indoors or outdoors—but they always seem to be absorbed in the moment.

“With the groupings of figures, I am thinking about narrative in a different way. There’s an activity, or a common cause or a sort of camaraderie, something that’s bringing them all together,” Yiadom-Boakye says. “This is linked to my wanting to think about the relationship of figures and what it is they are all here for… why are they there together? What is the purpose of that meeting?”

Later or Louder or Softer or Sooner (2013)

This is one in a series of paintings that nod to the dancers of Edgar Degas, who, along with Walter Sickert, Édouard Manet and John Singer Sargent, is frequently referred to by Yiadom-Boakye in her work. “I’ve been influenced by historic painters who share a certain devil-may-care mode of working, who were not so concerned with formal perfection or academic rules, but with the physicality of paint, the act of painting,” she says. The women in her earlier works were directly, even aggressively, frontal, but these dancers often turn their backs and avoid our gaze. “It’s deliberate that they’re not looking towards the viewer. They’re always looking away and you just get a sense of them,” the artist says. “I’m very careful about how female beauty appears. I like that they’re sensual and sexy and beautiful, but they’re not looking forward. They don’t give you everything.”