Every ten years, a few artists experience a double shot of prestige, by featuring in both the quinquennial Documenta exhibition and Skulpur Projekte Münster, which occurs once a decade. This year, Nairy Baghramian is one such artist. This Berliner, born in Iran in 1971, takes an often irreverent approach to the language of sculpture, architecture and installation, which has led to recent solo shows at, among others, the Serralves Museum, Porto (2014) and Smak in Ghent (2016)—the latter show travels to the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, in September. Her enigmatic and tactile works allude to the body, to design and sculptural history. Subtly, they include loaded content; issues of gender and identity, Modernist utopian ideals, public and private space. Her work for Documenta in Athens is emblematic of her approach: taking the nomadic theme that underpins Adam Szymczyk’s idea to open the show first in Greece, she returned to her work The Iron Table (2002). That installation is based on an evocative short story by Jane Bowles that conjures complex ideas about language, gender and the Western quest to colonise new space. For Athens, she reimagines this original work as a sculptural sketch.

The Art Newspaper: What made you choose to revisit an earlier work in Documenta?

Nairy Baghramian: When I started thinking about the concept of this Documenta, curated by Adam Szymczyk, and we started discussing his motivations for turning his attention southward—as a way of leaving the familiar terrain of Kassel and extending Documenta to Athens – I thought of an earlier work of mine, The Iron Table, from 2002. It raised similar questions and, at the time, I thought it touched on something important. Back then, shortly following the events of September 11, I had created an installation based on a short story by the author Jane Bowles—a beautiful, unfinished short story in which she addresses a desire shared by several intellectuals who had moved to North Africa. In the text, Bowles makes quick work of dismantling their utopian idea of the desert as a free zone, where you could live at a remove from socio-political concerns. In just a few pages, she describes the nomadic Modernist struggle with colonial and colonised ways of thinking, and she exposes the ethical and philosophical conflicts of that movement. She does so in formal, cultural and spatial ways, and gender as well as racial and ethical issues play a significant role in the text.

Since our current moment is so permeated by day-to-day politics, I had the feeling it might be the right time to point out that certain questions have been around for some time, and that some still remain unanswered. Documenta, given its history and the way it relies on the idea of a continuum, seemed to be the perfect context in which to respond; not with a new work, but by once again establishing a connection to Jane Bowles’s analysis from the 1940s.

How do you translate your thoughts about a piece of literature into a sculptural language?

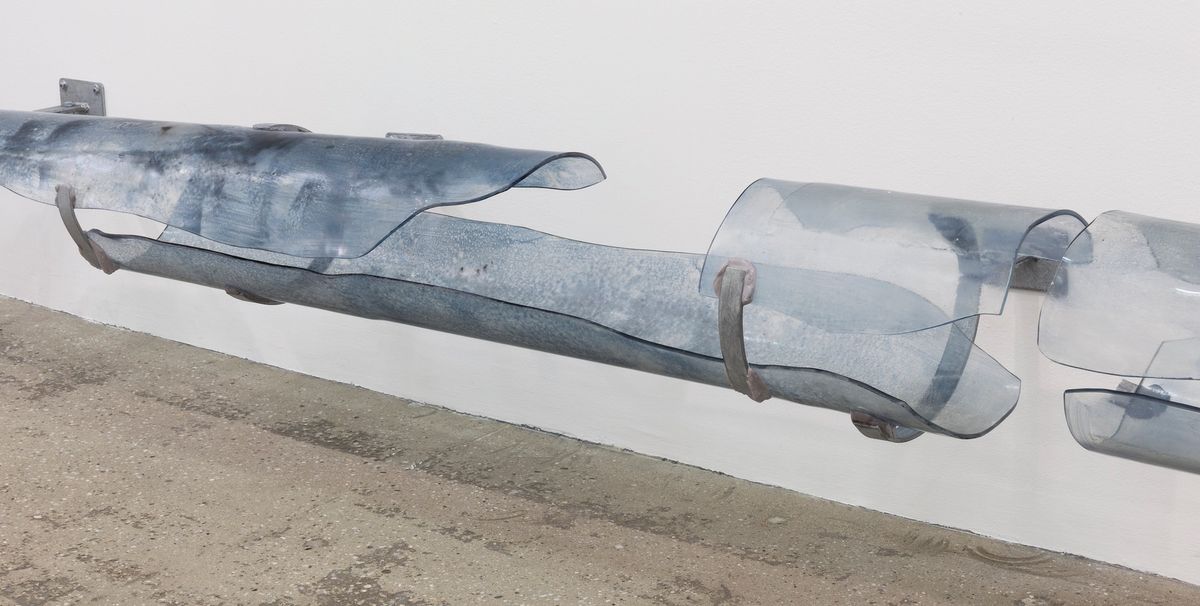

In terms of The Iron Table, this is a process that I had established years before. Jane Bowles’s writing seemed to me to possess both a fictional capacity and a formal one. It allows a way of thinking about the complexity of the body, gender, and territory that, for me, was already sculptural. Later on, I dealt with the question of how to present the idea in Athens as well. I thought it might be interesting to introduce a chronological reversal – by developing a sculpture for Athens that would function like a three-dimensional drawing and a rough draft of the original work. That’s why I gave it the title The Drawing Table. The rough draft, which is more like a sculptural sketch, follows almost 15 years after the original sculpture and thereby opens up a sweeping temporal horizon. Still, in its formal structure, it remains provisional and temporary. It’s almost as if, just like that, it could be picked up and reinstalled in another location.

Do you think in terms of imagery—metaphor and simile—when you are making your work?

Images emerge, but just as quickly, they disappear. They have to both surface and re-submerge in order to be verified and gradually to solidify. And that takes time. Given the art world’s compulsion for a fast pace, I sometimes get the sense that there isn’t enough time for this process to occur, that we put pressure on ourselves to call forth images and metaphors that take hold quickly, in order to satisfy a thirst for sensation and spectacle. As a result, increasingly, art production looks to day-to-day politics as a potential source and often elicits short-lived illustrations.

Does your work for Münster this year relate to the piece you made there in 2007?

My work from 2007 and the new work have relatively little to do with one another, both formally speaking and in terms of how they’re presented and their locations in Münster. In 2007, I showed a sculpture in a rather inconspicuous place between the city centre and an outlying area, which many local inhabitants and students passed by every day on their way to work. Still, many probably failed to take notice of the sculpture, which deviated to a significant extent from normal demands regarding dimension, materiality and site – especially since the work was installed on a non-site, in a public parking lot. Back then, I wanted to experiment with Sculpture Projects Münster and Kasper König’s intentions, and to question both the potential and the effect of public sculpture. I wanted to see how public space compared to the protected space of institutions and what kind of effect that has on sculpture. Ten years later, Kasper König, the curatorial team Britta Peters and Marianne Wagner, and I sought out a spot charged with history. We decided on the Erbdrostenhof, an 18th-century Baroque palace that has been rebuilt. In 1987, for example, Richard Serra exhibited his work Trunk there. I wanted to use that spot to reflect on the 40-year history of Sculpture Projects Münster. Despite the way the location differs from my work in 2007, I think similar questions are raised by the exhibition concept’s almost contradictory treatment of public sculpture in Münster as a temporary experiment. Normally, sculpture in public space is bound to an idea of permanence.

What are you making for the space?

The Erbdrostenhof has a quite prominent courtyard in front and a rather too purpose-oriented courtyard in the rear. There, I will install sculptures from my ongoing series Privileged Points, which I first exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 2011. The Privileged Points are bent, lacquered, metal rods on which the excess paint I have applied has formed into drips and hardened. They indicate ideal spots for the display of works, either in museums or on walls or on the ground. In Münster, they mark the place of sculptures in public space, and this time they have been adapted in size and materiality to the purported needs of an outdoor location. The lacquered, cast-bronze forms, which have been transported in parts, lay stacked on the ground in the rear courtyard – in anticipation or expectation of their future installation or their removal to another exhibition site. Meanwhile, in the front courtyard, one of the Privileged Points, which is still in pieces but has been brought together in order to be welded, seems closer to being a permanent installation. That said, the support structure holding them up makes clear that they are temporary.

Your work for Münster 2007 was graffitied. How did you react to that—was it expected?

Yes, I had to anticipate the possibility. And the work wasn’t only spray-painted; cars also regularly parked right next to it. You have to take that into account when sculpture is shown in an unprotected space. That’s part of its reality. In 2008, following an invitation from Adam Szymczyk, I showed a work in the Neue Nationalgalerie as part of the Berlin Biennale. It dealt with the transparent [glass] membrane of the Mies van der Rohe building. Two nearly identical pieces of the same sculpture were placed facing one another on the inside and on the outside of the building. Skaters soon realised they could use the part outside as a skate ramp, and the surface was badly damaged. Then, as well, I witnessed what was happening and later chose not to restore the work.