In May 1997, an event took place which is beginning to look like a watershed in the contemporary art market. Sotheby’s New York held the forced sale of a collection of very recent contemporary art, most of it not at all the blue-chip sort that you can hang over your sofa in a painless sort of way, but challenging, not to say inconvenient, pieces such as Rachel Whiteread’s large amber mattress sculpture.

Many thought this very bold of Sotheby’s, but the gamble paid off, and the sale was 90% sold by value, 83.7 % by lot, with a total of $15.2m. The mattress piece fetched $150,000, way exceeding its estimate of $30,000 to 40,000.

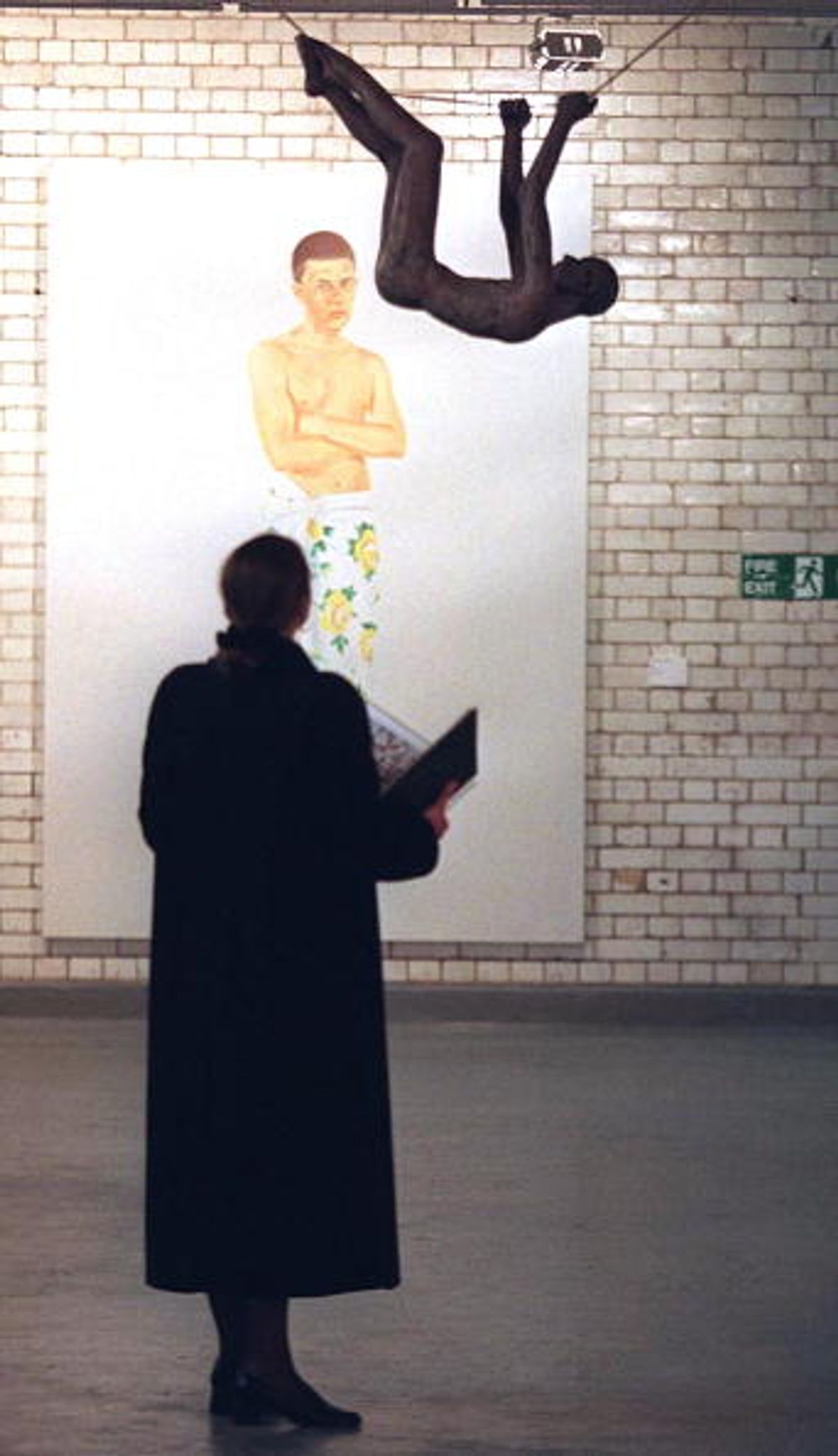

Christie’s London followed suit this April with its contemporary art sale presented for the first time, not in the grand, classical rooms of King Street, but in a disused industrial building in Clerkenwell.

Ironically, this imitation of the spontaneous, grunge art culture of the East End and South London, was, a Christie’s employee confessed, so expensive that it would be difficult to see a true profit on the sale, but it was a triumph of packaging that launched the auction house in direct rivalry with the galleries. The sale totalled £2, 826,370 (including premium), 87% sold by lot.

Admittedly, these were not rank outsiders; most of the artists already carried plenty of form, to use a racing term, without, on the whole, being outstanding examples of their kind. The names included Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Jannis Kounellis, Mario Merz, Andres Serrano, Cindy Sherman, Sigmar Polke and Damien Hirst and so on.

Last month’s New York sales at Sotheby’s, which totaled $42.3m (part I, 92%, part II, 80.3% sold by value) and this month’s at Christie’s are the confirmation of this policy to extend the auction houses’ role beyond that of an agent into the kind of art that has remained, until recently the preserve of the retail, that is the gallery, side of the market.

The contemporary art market has been in recovery since 1996, but the auction houses have a problem. There is simply not enough quality art to sell and the beast must be fed. They need to be continually developing new markets, both for goods and clients.

They can no longer wait passively until auction time to make business but are active on the retail side, as well as buying and selling for clients.

Tobias Meyer, the head of contemporary sales at Sotheby’s expresses it succinctly, “I only think we should put things to auction that are going to fly. If they are not going to fly there’s no point; then you need to sell them privately. But just because they can only be sold privately doesn’t mean that we, as Sotheby’s, cannot partake in that transaction. Here, in a nutshell, is the reason for Christie’s and Sotheby’s acquisition of dealerships in recent years.

The auction houses involvement in retailing began in 1990 when Sotheby’s, together with Acquavella Gallery, paid $142.8m for the 2,300 or so classic Modern works in the estate of Pierre Matisse, the New York dealer and youngest son of Henri Matisse. Having then acquired the prestigious and once vigorous Andre Emmerich Gallery in 1996, Sotheby’s advanced into the field of the avant-garde last September when it bought Deitch Projects, one of the hottest new contemporary galleries in New York.

Diana Brooks, president of Sotheby’s Holdings, announced that Jeffrey Deitch, the art dealer and art adviser, had joined Sotheby’s to develop and manage a 20th-century art-gallery programme.

Sotheby’s joint-venture purchase, for a reputed sum of $1m, was designed to “emphasise the representation of leading contemporary artists and to concentrate on the history of vanguard art of the twentieth century,” said Ms Brooks.

Jeffrey Deitch provides Sotheby’s with market access and real flair for sensing the next trend in the market. He has been on the scene since 1974, first with John Weber Gallery, later for nine years as private banking division adviser at Citibank and then as a private curator and collection consultant. “I’ve slowly been doing transactions with the auction house over the past five years, so creating the gallery programme with them was really a natural step.”

As for Christie’s, which has bought Spink, Thomas Gibson and Leger, it has even blurred the boundary between museum and commerce (not for nothing did the catalogue of April’s auction in London look and read like a highly designed exhibition catalogue). In February, Christie’s opened “Painting Object Film Concept: Works from the Herbig Collection.”

This was billed as an exhibition, not a sale, but most of the collection, Minimalist and Conceptual works collected during the 60s and the 70s, has since turned up in the auction scheduled for 4 June.

The exhibition came with full institutional apparatus: it was organised by a former curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Chicago, Richard Francis; there was a commissioned, site-specific, street installation by France’s most famous living conceptual artist, Daniel Buren, and an accompanying catalogue text by international curatorial celebrity Harald Szeeman, the director of the Kunsthalle Berne from 1961 to 1969, organiser of the landmark 1972 Documenta V exhibition in Germany, and creator of Aperto, the young artists’ pavilion, at the 1980 Venice Biennale.

Neal Meltzer, 32-year-old head of contemporary sales at Christie’s and son of Pop art collectors, says, “This is really the art of the future. We want to let people know that the auction houses are going to invest in the contemporary market and stand behind it and believe in it. The fact is, that of all areas, this is the one that still continues to grow”.

“There are people who have heard of Christie’s but who don’t go to young galleries. Christie’s offers an incredible audience to a market of artists that have never been exposed in that way. It can be extremely exciting and very, very good for their market and their careers—or for just communicating what their work is about.”

Don and Mera Rubell, collectors for 30 years (of Jean Michel Basquiat, Gilbert and George, Peter Halley, Jeff Koons, Richard Prince, David Salle and Julian Schnabel) are more sceptical about the potential of the auction houses to assist living artists. They think a young artist is supported better by a gallery than by an auction house because the latter does not deal in careers: “The auctions, like the Whitney Biennial, will define who the stars will be” .

Galleries may be wonderful; they support artists and make career decisions, but ultimately the value of an object is what someone will pay for it in an open market. When the first Schnabel plate painting was sold to Anita and Burton Reiner for $100,000, the sale fixed Schnabel as an important artist in the public’s eye.

The result of the auction houses’ entrance into the contemporary market will be a greater openness about pricing and increased liquidity for art owners, and this may well help develop the market. As Jeffrey Deitch says, “This is very much about the collectors. The people who have bought the art have gone to the auction houses and asked them to sell the works.”

As for the art galleries, it remains to be seen whether they will benefit from this potential expansion of the market , or whether they will get left just with the unprofitable role of supporting the artists at the beginning of their careers while the auction houses cream off the art just as it begins to be established.

Douglas Baxter, PaceWildenstein

“One can’t be too surprised by Sotheby’s push into the retail market. Look who owns the company: Alfred Taubman, a real estate magnate who made his fortune by building shopping malls. He’s not a retailer by profession, but he’s got to sell those malls to retailers, and if he’s going to be successful, then he’s got to put himself into the shoes of a retailer. And he is very successful.”

Richard Feigen, art dealer

“There is a dearth of material; you can see it reflected in the Impressionist and Modern, and also in the Old Master auctions. While struggling for material to sell, auctioneers have got more and more into the post-Second World War period and some of the contemporary market, but I can’t imagine that they want to get in bed with Jeff Koons or a lot of these artists on a primary market basis and then have to cope with all the personality problems. It’s like people opening up a restaurant: basically, they love fine cuisine, but unless they run the Tavern on the Green, they can’t expect to make a lot of money. There is not a lot of money in the contemporary market; there is a lot of work. You have to be committed to doing it for a lot of other reasons besides the money.”

Jeffrey Deitch, Deitch Projects and Sotheby’s

“In the mid 1970s, people who bought new art did not expect to resell it. It was not so much a market as a kind of interesting passion. I’m nostalgic for the time when collectors were more open and didn’t expect to be able to get their money out. If people feel that they should be able to get their money out, I wouldn’t argue with them, but that has really very much changed how they approach new art.”

Ann Freedman, Knoedler and formerly Andre Emmerich Gallery

“Art dealing is about placement, and auctions and auction houses will always be about displacement. [The auction houses] will say they are not selling the art, that they are placing it, but it is in their best interest to see that the art keeps churning. So they displace, place, displace... I think that it is not possible to blur the lines as much as they perhaps would like. There are some clear distinctions, one of which is the tradition of dealers representing artists. Selling works of art is one aspect of dealing and service to the artist is another.”

Don and Mera Rubell, collectors

“We have bought some good pieces at auction in the past five years: Peter Halley, two Basquiat paintings, and, when the market in his work dipped, Jeff Koons. We buy many of the same things at auction that we do at the galleries. If a great piece comes up—where ever it comes up—we will be willing to go for it. Do we prefer auctions to galleries? No. But we know what the galleries charge, and if it is a better piece at a cheaper price, we will go with auctions.”

Some recent public prices

- Anselm Kiefer, “Midgard” $497,500 (£296,130)

- Brice Marden, “2 part study”, $475,500 (£283,035)

- Jim Dine, “The mirror the meadow”, $420,500 (£250,297)

- Sigmar Polke, “Totenkopf (Quecksilberkosmetik)”, £243,500 ($409,080)

- Jean-Michel Basquiat, “The guilt of gold teeth”, $387,500 (£230,654)

- David Hockney, “Oversized pool (paper pool 23)”, $387,500 (£230,654)

- Damien Hirst, “God”, £188,500 ($316,680)

- Barry Flanagan, “Nijinski hare”, £166,500 ($279,720)

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled, £106,000 ($178,080)

- Anish Kapoor, “Pot for her”, £45,500 ($76,440)

- Tom Wesselmann, “Little still life no.25”, $70,700 (£42,083)

- John Chamberlain, “Opian angel”, $46,000 (£27,380)

- Christo, “Wrapped island (project for the South Pacific Ocean near Australian coast)”, $36,800 (£21,904)

- Chuck Close, “Maquette for ‘Alex’”, $18,400 (£10,952)

- Meg Webster, “Contained water”, $9,200 (£5,476)

- Christian Boltanski, “Composition heroique”, $9,200 (£5,576)

- William Wegman, “Social studies”, $6,900 (£4,107)

- Cindy Sherman, “The secretary”, $4,887 (£2,908)

- Alison Wilding, “Shady 1”, £2,070 ($3,455)

- Jannis Kounellis, Untitled, £2,070 ($3,455)

- Yasumasa Morimura, “Doublonnage (dancer III)”, $3,450 (£2,053)

- John Cage, “Wild edible drawing no.9”, £1,955 ($3,284)

- Anthony Gormley, Untitled, £1,495 ($2,511)

• Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper with the headline "A bigger market for all?"