One of the more surprising of Van Gogh’s still lifes is a colourful depiction of two crabs. According to an authority at London’s Natural History Museum they are both probably the same individual—and female. Paul Clark, a specialist in various decapods (ten-legged crustaceans), was able to confirm the specimen's sex because it is lying on its back, displaying a broad abdomen.

The crab is a Cancer pagurus, an edible species, so Van Gogh probably bought it in a food market.

Van Gogh’s crab is missing its first pair of walking legs, which would have been directly behind its claws. Crabs often lose their claws and legs, but these can be regenerated.

Two Crabs is on long-term loan to London’s National Gallery. This week it was redisplayed as part of the gallery’s major rehang, which will be fully unveiled with the reopening of the Sainsbury Wing on 10 May.

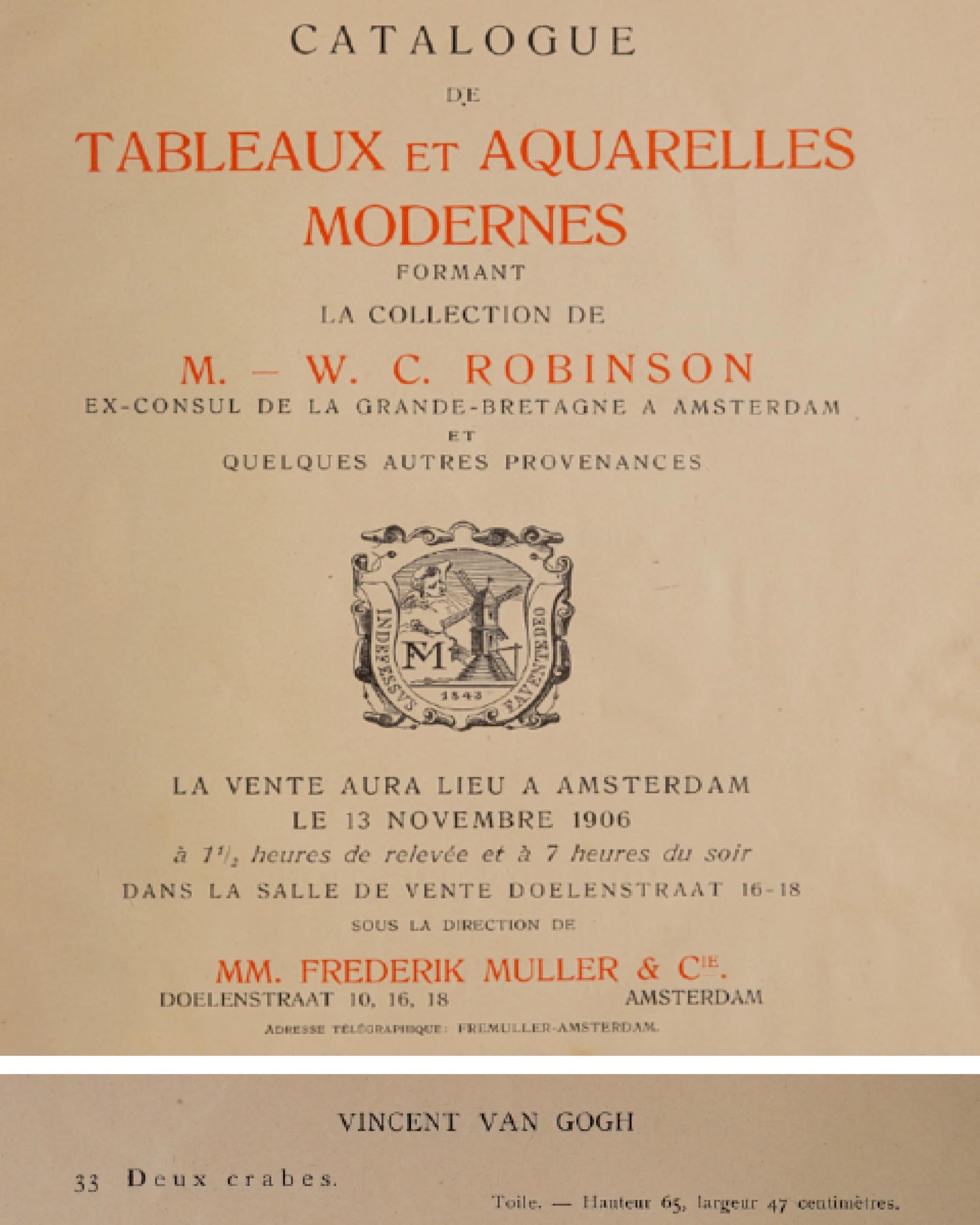

Bought by a British collector

Although it is not widely known, Two Crabs was the first Van Gogh to be bought by a British collector. He was William Cherry Robinson (1834-1908), the UK consul in Amsterdam from 1882 to 1906. A successful businessman, he was involved in the coal industry.

In May 1893 Robinson bought Two Crabs from Jo Bonger, Vincent’s sister-in-law. By this time she had probably only sold around eight Van Gogh paintings of the many hundreds she had inherited, so it represented a very early sale. Robinson paid 200 guilders, then equivalent to £17.

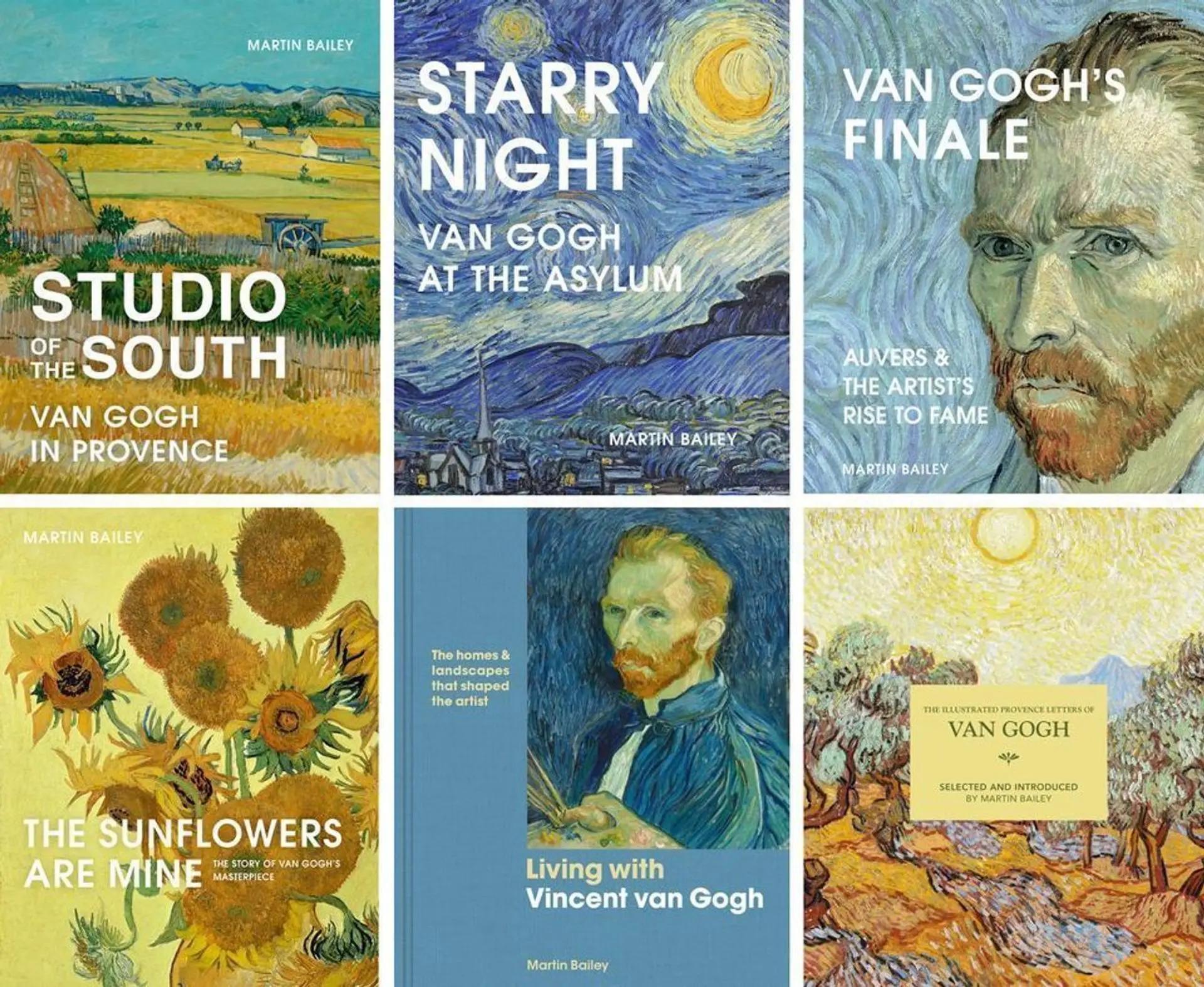

In 1906, just before leaving Amsterdam to retire in his native England, Robinson sent his huge collection of mainly 19th-century Dutch art to auction. There were nearly 200 works, many by artists who are now long forgotten. The Van Gogh painting was, in style, atypical of his rather more conventional taste.

Auction catalogue for the collection of W.C. Robinson, Frederik Muller, Amsterdam, 13 November 1906

Two Crabs did badly in the auction, selling for just 100 guilders, half of what Robinson had paid 13 years earlier. Although 26 paintings were illustrated in the auction catalogue, the Van Gogh was not among them, confirming that it had been regarded as of secondary importance. Two Crabs was bought by the Paris dealer Bernheim Jeune.

At the same auction Robinson also sold a Van Gogh drawing, Peasant in a Cart harnessed to an old white Horse. This work remains unidentified, although there is a similarly titled drawing at the Van Gogh Museum, Donkey and Cart(October 1881).

In 2004, nearly a century after the Amsterdam auction, Two Crabs was sold at Sotheby’s, going to another British collector for £5.2m. Shortly after the sale the anonymous buyer generously lent the painting to London’s National Gallery, where it remains on view.

When did Van Gogh paint crabs?

There is a second, related Van Gogh still life, with a single crab, A Crab on its Back, at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum. This crab is very likely the same individual, since it is also a female missing its front set of walking legs. The Amsterdam painting is similar in style and colouring to the London one, so they must have been done at the same time.

Van Gogh’s A Crab on its Back (August-September 1887)

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The difficulty is that two museums disagree on the paintings' dates. The National Gallery says theirs was painted in January 1889, when the artist was in Arles. The Van Gogh Museum, which has the authoritative specialists, believes its picture was done in August-September 1887, when he was in Paris. A 16-month difference may sound relatively inconsequential, but Van Gogh’s style was developing very rapidly, so art historians are keen to differentiate between his Paris and Arles works.

The dating remains a puzzle. Although crabs are caught in the Mediterranean they much more commonly come from the Channel area, which might suggest Van Gogh was more likely to have painted them in Paris. But the strong colours and brushwork are arguably more suggestive of his later paintings from Arles.

Art historians who plump for Arles cite a letter from Vincent to his brother Theo on 7 January 1889, when he wrote: “I’ll begin by doing one or two still lifes”. Those who believe the crab paintings were done then, two weeks after Van Gogh mutilated his ear, have sometimes seen a psychological element in Two Crabs: the creature lying helpless on its back might reflect the artist’s own vulnerability. But it is always risky to read too much psychology into Van Gogh’s art.

However, having come out of hospital on 7 January, it is questionable whether Van Gogh would have ventured out that very same day to buy crabs, which might well have been difficult to find. It would have been much easier to compose a still life from objects close at hand in his Yellow House.

The mystery over the dating might be solved by bringing the London and Amsterdam paintings together for a technical examination. It would also be interesting to display the paintings side by side, since they have not been shown together for a century.

Why did Van Gogh paint crabs?

Crabs might appear a curious subject for a still life, but they appear frequently in Japanese prints, which Van Gogh greatly admired. Katsushika Hokusai was particularly enamoured of them, with one of his images featuring in the French periodical Le Japon Artistique. Van Gogh owned this issue of the magazine and described Hokusai’s crabs as “admirable”. The Hokusai print appeared in the June 1888 issue, so this particular image would only have impacted on Van Gogh’s paintings if they were done in January 1889.

Katsushika Hokusai’s Crabs in Seaweed and Van Gogh’s Two Crabs

Reproduced in Le Japon Artistique, June 1888 and private collection (Van Gogh)

Van Gogh may well have chosen a crab for his still life because of their colour: he set its orange body and shell against a powerful green background—two complementaries. In his two paintings the colour contrast emphasises the rough claws and spiky legs of the menacing sea creature.

Van Gogh’s Two Crabs in the National Gallery’s new redisplay, hanging beside Van Gogh’s Chair (December 1888-January 1889)