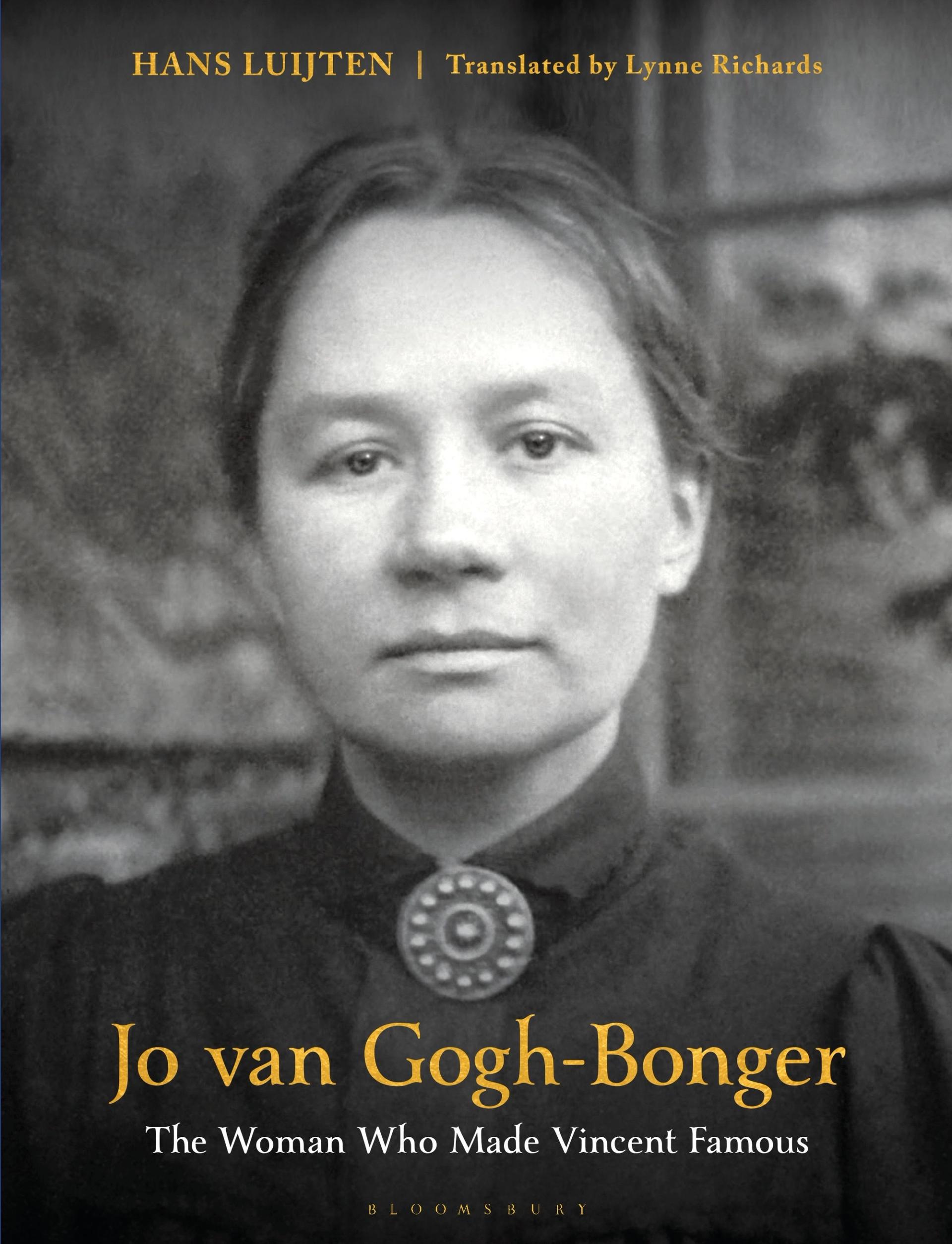

English-speakers now have the best opportunity to discover the life of Vincent van Gogh’s sister-in-law Jo Bonger, who preserved and promoted the artist's work. Two years ago, the first biography was published by the Dutch specialist Hans Luijten—and it is now coming out in the UK and the US in November. In more than 500 pages, Jo van Gogh-Bonger: The Woman Who Made Vincent Famous presents a fascinating and detailed account of her astonishing life.

Cover of Jo van Gogh-Bonger: The Woman Who Made Vincent Famous, published by Bloomsbury, London, 3 November

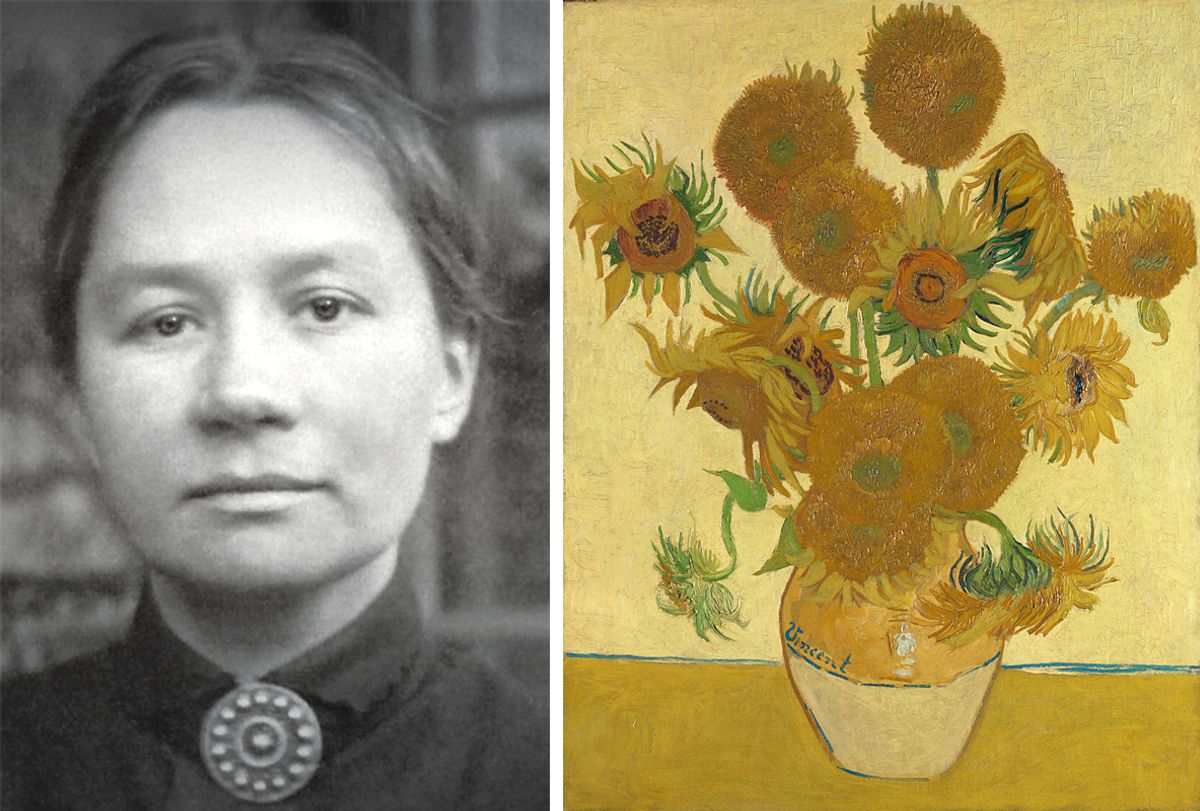

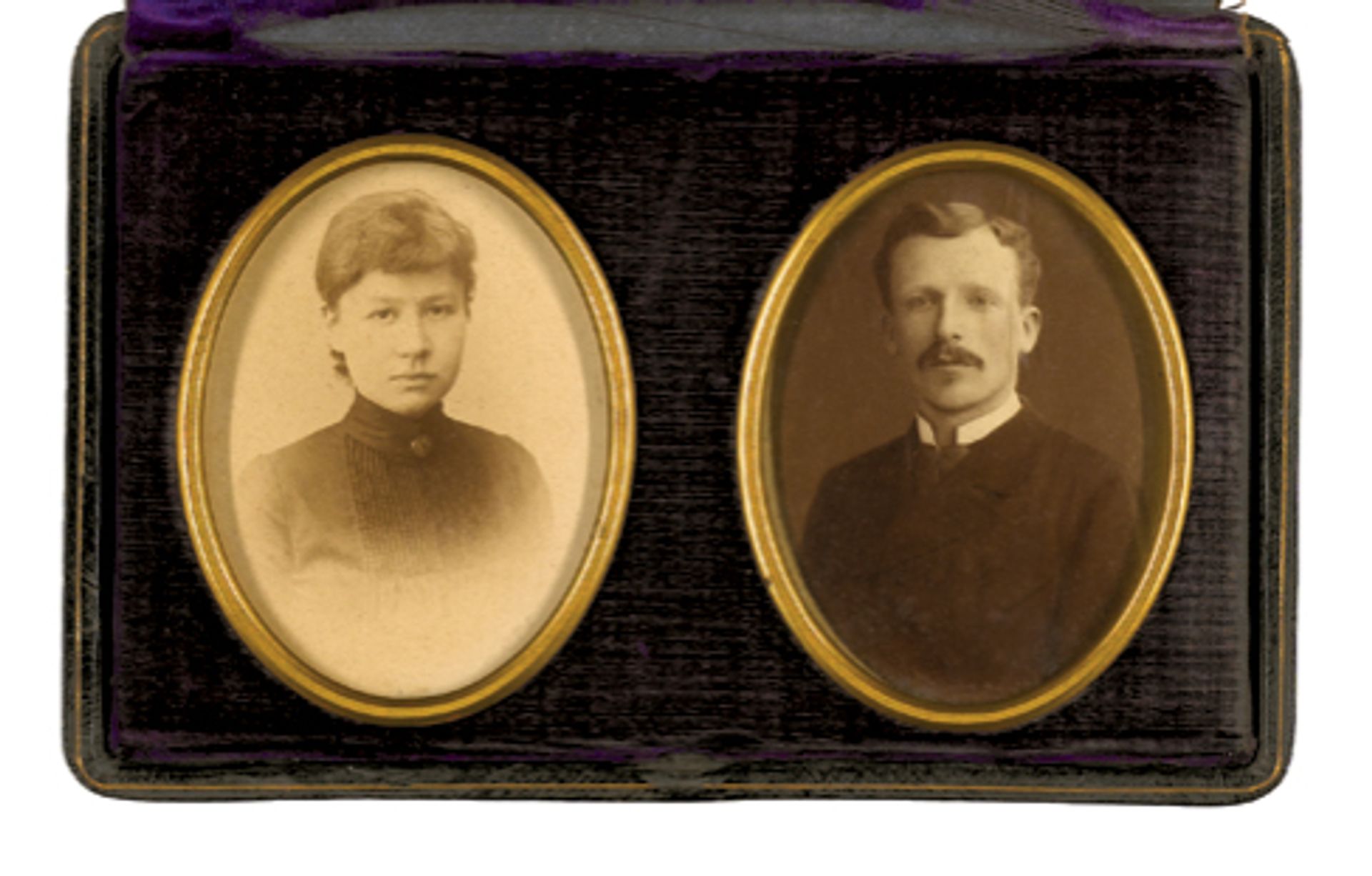

Johanna (Jo) Bonger (1862-1925) ended up playing an absolutely crucial role in the Van Gogh story. In December 1888, the month that Vincent mutilated his ear, she encountered Theo, Vincent’s younger brother. They fell in love and, within days, became engaged.

A case holding photographs of Jo Bonger and Theo van Gogh (1889) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

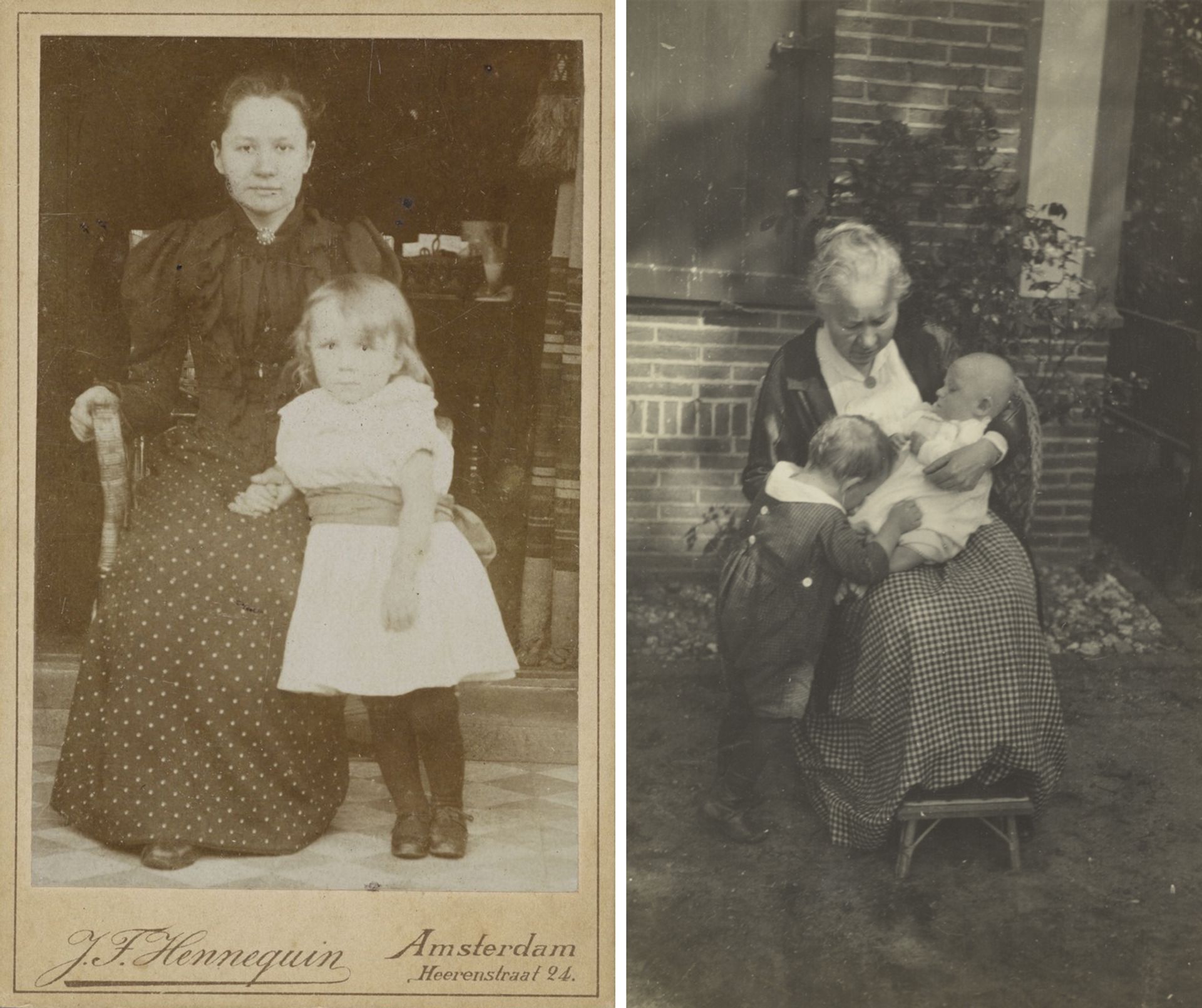

The couple married in Amsterdam in April 1889, setting up home in Paris, and in January 1890 they had a son, whom they named Vincent after the artist. It was to be a tragically brief life together, with their happiness initially overshadowed by the disaster of the ear incident.

Vincent, the artist, committed suicide in July 1890 and six months later Theo died of what was probably syphilis, in terrible agony. Only one painting is certain to have been sold during Vincent’s lifetime, so the overwhelming majority of his surviving works passed first to Theo and then soon afterwards to Jo and her infant son. From then onwards, Jo devoted the rest of her life to her two Vincents: her son and the memory of her brother-in-law.

As the biography records, Jo Bonger began by lending pictures to exhibitions in the 1890s, to spread knowledge about the artist. In 1905, she organised a Van Gogh retrospective in Amsterdam. Comprising of 443 works, this is still the largest exhibition ever to be held of his work. Among other major shows she supported was one of Modern art in Cologne in 1912, known as the Sonderbund exhibition (the 22 loans included the Sunflowers [August 1888]).

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (August 1888), in a plain white frame, and other works lent by Bonger to the Sonderbund exhibition, Cologne, 1912 Credit: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne

Bonger also cannily promoted sales of some Van Gogh works, dispersing pieces to private collections and later to museums—and thereby raising his profile. Although Bonger’s minimal experience of the art world all came from her brief marriage to Theo, who was a dealer, Luijten records that she “learned to play the market shrewdly”.

Her perseverance was for idealistic reasons. As the biography explains: “First and foremost, she wanted, come what may, to complete the task that Theo had set himself in 1890—publicising Vincent’s art. Secondly, and no less importantly to her, she supported the socialist view that looking at art could elevate people.”

I have wondered whether a subsidiary motive in selling Vincent’s art might have been to provide an income. But Luijten points out that Bonger had considerable investments, partly from her time with Theo, so “she never really needed the money from sales”.

Bonger’s third way of promoting Vincent’s work and legacy was to publish his revealing letters, which provide a deep insight into his life and art. The first comprehensive volumes were published in Dutch in 1914.

Photographs of Jo Bonger with her son Vincent, 1892 (left); and with her grandsons Theo and Johan on her lap, 1922 (right) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

A fascinating point that emerges in the biography is the observation that Bonger switched her efforts after 1914 to promote Van Gogh’s work in Britain and the United States. Collectors there had been late to come under the artist's spell (the US angle is explored in an exhibition in Detroit, Van Gogh and America, until 22 January 2023). As Luijten puts it, Bonger placed an emphasis on Anglo-American sales in the hope that this would “stimulate curiosity about his letters”.

Targeting an Anglo-American audience helps to explain why Van Gogh’s greatest version of the Sunflowers (August 1888) came to London’s National Gallery. In October 1923, Bonger was loathed to part with the floral still-life, arguing that the Sunflowers belonged “in our family”. She had looked at the picture “every day for more than 30 years”.

Luijten puts forward an interesting idea on why, some weeks later, Bonger relented and agreed to a sale: she came to realise that the presence of the Sunflowers in the UK’s greatest gallery might help to encourage a publisher for an English translation of Van Gogh’s letters.

Bonger at the time owned two versions of the Sunflowers with a yellow background, and I have often wondered why she reluctantly agreed to part with the finest example. This was the original version painted in August 1888 for Paul Gauguin’s bedroom in the Yellow House. She also owned a copy that the artist made in January 1889. The copied Sunflowers was saved and is now the star attraction in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Luijten’s research suggests that she wanted the best version to represent Van Gogh in England.

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers: the original (August 1888), owned by the National Gallery, and the later version (January 1889), which is in the Van Gogh Museum Credits: National Gallery, London; and Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

During the negotiations on the sale, Bonger had written to Jim Ede—a young curator at the National Gallery’s branch at Millbank (now Tate). “If you read the English translation of the letters, your enthusiasm would still increase”, she wrote. Finding a publisher was at the forefront of her mind.

In February 1924, as the sale was concluded, Jo’s son Vincent recorded that his mother had finished the translation, “but so far no English publisher was sufficiently interested”. He then added: “No doubt the recent exhibition and the pictures in the National Gallery will stimulate… the interest in Van Gogh.”

And so it was to be. Bonger began discussions with two publishers, Constable & Co (London) and Houghton Mifflin (New York). Sadly, she did not live long enough to witness the actual publications. The offer of a contract came through a month after her death in September 1925, at the age of 62, and the two volumes were published two years later.

But what about the rest of the family collection? Surprisingly, there is nothing to suggest that Jo and her son Vincent ever discussed the possibility of establishing a museum. After many decades, it did eventually go ahead, with her son generously reaching an agreement with the Dutch state in 1962, leading to the opening of the Van Gogh Museum in 1973.

As Luijten points out, it remains “puzzling and inexplicable, however, why he [Bonger’s son Vincent] made absolutely no mention of his mother’s name in his speech at the museum’s opening”—considering all that she had done for her brother-in-law. Family dynamics can remain obscure, even to biographers.

Luijten’s magnificent tribute to Bonger concludes: “Thanks to her unbridled efforts, she unmistakably contributed to Van Gogh attaining a lasting place of honour in cultural history.”