The Mexico City-based artist Ana Segovia’s winking, neon reinterpretations of the Mexican cowboy (or charro) archetype bend and break preconceived notions of normative machismo, translating film stills from Mexico’s cinematic Golden Age into an unabashedly queer new language. His current exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA), part of the institution’s recently revived Focus series, draws from the content of a single film, I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You (1983), a synth-forward musical love story between Buck, an artist, and Mario, an undocumented ranch hand living in a fictional Southwestern town. Just one thing—this movie is not real.

Segovia yearned the film into being, crafting a script, storyboarding imagery, even creating a fake director in an attempt to locate queer comfort in the guilty pleasures of his identity and artistry in tandem, Segovia takes on themes of construction and recombination with an equal helping of satire and tenderness, asking big questions about the masculine mythos of cultural production. His MoCA show not only reflects the choreography of gender performance but actively engages visitors in the dance—viewers must walk a specific path around the works, armed with portions of the script held at an arm’s length from Segovia’s fluorescent monument to desire.

Many of the paintings in the MoCA exhibition are mounted on a wooden frame; Segovia says he wanted to “allude to the construction materials of a set, which is something that’s alive”

Photo: Jeff Mclane. Segovia Works: © The Artist; Courtesy of MoCA Los Angeles

THE ART NEWSPAPER: Your exhibition centres on a script for a nonexistent film—what was the process of developing this concept?

ANA SEGOVIA: It was honestly the funnest thing I’ve worked on. I was having a bit of a crisis when I first started. I felt I had exhausted alot of my typical subject matter of Golden Age Mexican cinema. I’ve always been interested in translating cinematic language into a more technical painting style. I’d been working on this archive and some John Ford Westerns for six or seven years, and I had this weird creative writer’s block. I was also going through some personal stuff, so I did what every millennial does: binge-watch nostalgic TV shows and movies. At the time, I decided to rewatch the big mainstream 1980s dance movies that I love: Dirty Dancing, Footloose and Flashdance. While I was watching Footloose, it occurred to me that I wanted the love story to happen between Ren and his best friend, Willard. I wanted my gay cowboy 80s movie. What would have happened if I had watched that when I was younger? If all these queer-coded 80s popular-culture products had embraced queerness? So I decided to write the movie that I wanted to watch.

I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You is essentially an ode to guilty pleasures. It was so much fun to invent—the director, the stars, all of it. I knew that I wanted to use this script as a jumping-off point for a series of paintings, and I started telling everyone that the movie was real. I started drawing out the storyboards for two or three major scenes in the movie, which is the MoCA show.

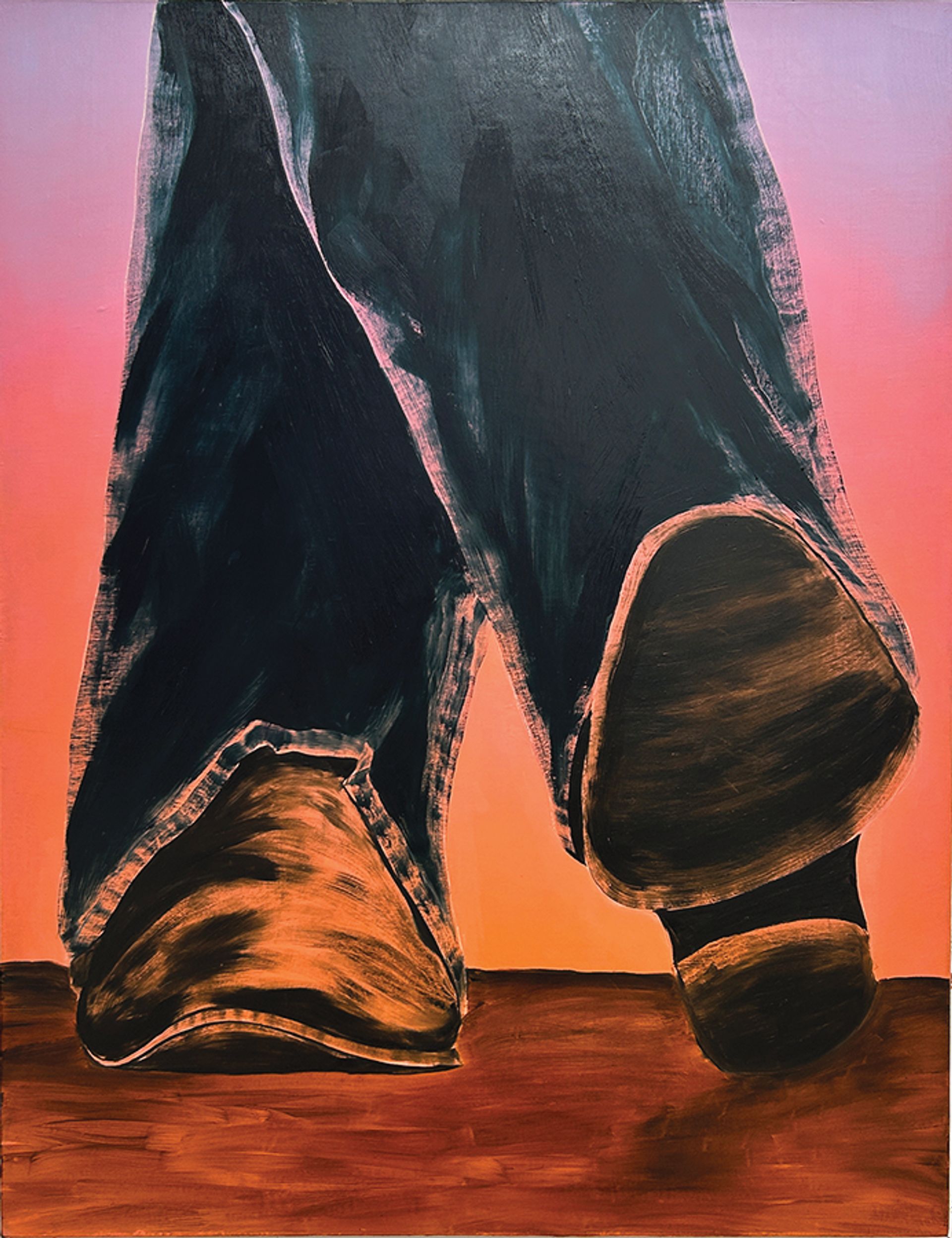

One of the suites of paintings is the dance montage, which is my favourite thing about 80s dance movies; I have this theory that, because of the advent of MTV, there was a visual language that contaminated mainstream movies—a lot of them are good, but they feel like an excuse to make a bunch of fun video clips. So I tried to hone into that montage language of very, very tight close-ups on the crotch and other body parts. Like, “How sexy, look at this person’s butt!”

I wanted to make a group of paintings that would behave as close as a painting can to the medium of film or video. They have a specific relationship to time, to movement, which is also a bit of the installation. You’re denied access to the gallery, so you can only look at the paintings while you move through the structures, and they reveal themselves. It creates this fragmented narrative steeped in mystery. It’s yet another window into this world that you’re never fully allowed to access, because it doesn’t exist.

The show features a lot of wooden armatures that the public has to move through in a specific way. How does that impact the way the work feels in the space?

I’ve always had fun removing paintings from the walls, thinking about how the body of the viewer relates to the object. I knew that for this, because it’s a stage show, I wanted to allude to the construction materials of a set, which is something that’s alive, and to find a way to make these paintings feel suspended.

It was a collaborative process with a very talented industrial designer, Miranda Moreno, who worked in my studio at the time. Their compositions are based on one of my favourite paintings, The Descent from the Cross by Rogier van der Weyden (around 1435). Miranda and I were looking at the composition of the Van der Weyden and the composition of the suite of paintings and thinking about a way the structure would accentuate those compositional links. That’s when we decided that the diagonals would help the eye move in a direction from this external object and accentuate that part of a very classical painting. When I was approached for MoCA Focus and I visited the gallery, the first thing I got excited about was making it into a hallway. It’s a show you have to see in transit. We created a space that makes you want to go in, but you can’t, like cinema.

Kicking off: Segovia’s cowboy-themed I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You #1 (2023) from the MoCA show

Photo: Jeff Mclane. Segovia Works: © The Artist; Courtesy of MoCA Los Angeles

Do you feel this new direction reinvigorated your interest in cowboy masculinity?

It did. It made me realise that I was taking the archive way too seriously. I was documenting and commenting on this thing, and it had to be super smart, well-researched and talk about culture and John Ford. But sometimes it can just be inspiration! Fictionalising is what art does all the time—it’s always something other than it is, it’s always telling lies. This opened a world of possibilities.

I’ve been obsessed with cowboy and charro culture since I was a kid. It defined how I’ve come to think of my own identity as a transmasculine person. I don’t ever think that I can do away with it. It’s something that’s fundamentally me, but my relationship to it has now changed, absolutely.

What is the role of humour in your practice? Do you see your work as satirical?

Oh yeah, I own that. I think about it as a self- deprecating sense of humour. I wake up every morning and think that I physically look like Paul Newman—a cowboy—and then I look at myself in the mirror, and I’m like, “Holy shit!” Then I’m also like, “You don’t wanna be Paul Newman, or Beto Fuentes, because those are very toxic approaches to masculinity.” What I find alluring and attractive is something I need to work on as a person, because that kind of masculinity that I revered when I was growing up not understanding I was trans is a problem. So I try not to take myself too seriously.

- MoCA Focus: Ana Segovia, Museum of Contemporary Art, Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, until 4 May