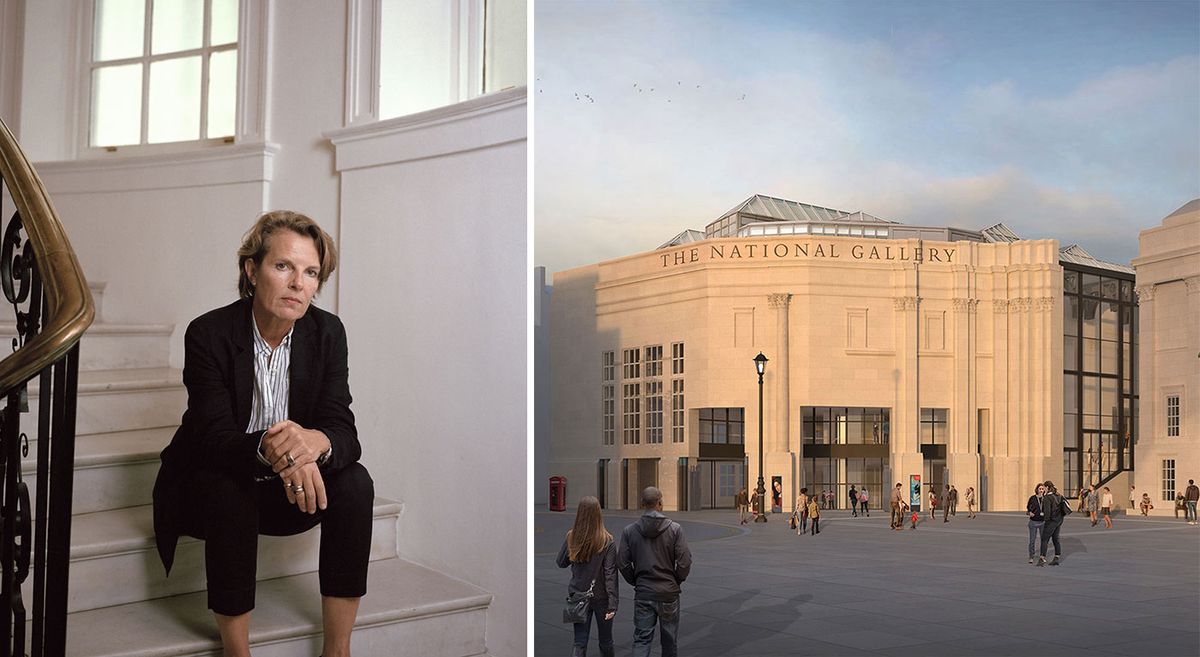

The architect Annabelle Selldorf felt the burden of place and of history in July 2021 when her New York-based practice won the commission to remodel and refurbish the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery in London.

“When we first won this competition, I was standing [in Trafalgar Square] thinking... It's me they hired. It's a big deal. It's a really big deal to be in this place. And every time that I come here, I am impressed with it," she tells The Art Newspaper. "How much Trafalgar Square means to people, means to the world”—as a symbolic heart of the UK capital. “The age, the place … nobody can escape that,” she says. “You can't be at all blasé about it.”

Selldorf was speaking during a tour of the Sainsbury Wing building site in early December, five months before the remodelled wing—originally designed by the pioneers of postmodern architecture Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown and opened in 1991—is due to reopen. Selldorf’s reimagining of the wing is the largest element of NG200, an £85m programme of capital projects at the National Gallery to mark its bicentenary. Her brief was to make the Sainsbury Wing a more welcoming entrance for the entire gallery—including the main building designed by William Wilkins in 1832-38—and to bring more light into the wing’s ground and first-floor areas.

More than 1,100 works by 400 artists: how the National Gallery collection will be redisplayed

The reopening will coincide with the final stage of the rehanging of the National Gallery’s collection, with the ground, first and second floors of the Sainsbury Wing being brought back into use. The galleries on the wing’s second floor have been closed but left untouched during the two-and-a-half-year remodelling, but will house a complete rehang of northern and southern Renaissance paintings down the great central corridor and two flanking enfillades of smaller galleries. The wing’s basement galleries, previously home to loan exhibitions including the historic Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan (2011-12)—but at present still serving as quarters to the building contractors’ immaculately organised site management, canteen and changing areas—will be brought back into use in September with the loan show Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller's Neo-Impressionists.

Sainsbury Wing's connection with Trafalgar Square

Many of the surfaces and finishes of the refurbished wing—Purbeck marble, grey-blue pietra serena, timber panels and flooring, glass both clear and slightly misted—are now in place, though largely covered in protective boards or padding while work continues. But the bones of the project are fully apparent when The Art Newspaper is given a tour of the site by Selldorf and Paul Gray, deputy director of the National Gallery.

Enough is complete to show the striking new perspectives within the wing and of Trafalgar Square outside. Selldorf’s plans for making the 1991 structure a better visitor experience included enlarging public spaces, letting in more light through new glazing, opening new sight lines to allow Venturi and Scott Brown’s great side-lit staircase to play its full part in the wing’s architectural drama, and improving the connection between the building’s interior and exterior spaces. Those plans—so fiercely criticised by a group of architects and critics and by Scott Brown herself when they were published in 2022—have been dramatically vindicated.

The wing now feels intimately connected to London’s most celebrated square with clearer lines of approach and a palpable link, whether seen from inside or out, between the wing and the Wilkins building.

One of the most memorable moments of the site visit comes when Selldorf indicates the sight lines which run eastwards from the first floor, in a grand architectural sequence—now clearly seen through the new, untinted glass—along the neoclassical stone façade of the Wilkins building, eastwards towards the eye-catching spire and pediment of the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields (1726).

“If you step back from here you see more of Trafalgar Square," Selldorf says as she points eastwards along the entrance front of the Wilkins building, “and you realise the sort of genius of the architectural gesture to have this angle [of the wing’s glazed facade] that brings in not only Trafalgar Square, but all the way across” the north side of the square.

The square within the square: a forecourt of the Wilkins building (right) has been reused to add an indentation in front of the Sainsbury Wing to make the entry into Sainsbury, Selldorf says, much more purposeful and deliberate Rendering: Selldorf Architects

National Gallery's "square within the square"

“My maybe greatest pride and joy is our little forecourt,” Selldorf says, “the square within the square.” It is a key element, she says, in making the connection between the Sainsbury Wing and the Wilkins building fully “legible”. “We pushed the lawn back and... captured a little internal courtyard on the Wilkins side,” she says. “And as a result of that, we get [an] indentation right in front of Sainsbury that makes the entry into Sainsbury much more purposeful and deliberate." She says she thinks Venturi in heaven will be thanking her for one thing in particular: "that by taking away that courtyard, you see that the foot [the cut stone base] of Wilkins [is] on the same level as Sainsbury. And it gives a kind of reading or legibility to this building. Which it really didn't have before. I think he would like that. It just feels clear. The connection between the square is so much more obvious”.

Selldorf's nod to the “genius” of Venturi and Scott Brown’s architectural gesture in angling the entrance façade to capture two perspectives of Trafalgar Square—the heart of the square with Nelson’s column, the Landseer lions and the Fourth Plinth as well as the view along the front of the Wilkins building— is part of her discovery during the project that these buildings are "so intimately connected”.

Annabelle Selldorf: "the architect of our moment"

The completion of work on the Sainsbury Wing is part of an extraordinary year for the German-born architect. The Frick Collection in New York is scheduled to reopen to the public barely a month before the London institution, in April, following Selldorf’s wide-ranging four-year refurbishment and remodelling of its Fifth Avenue Gilded Age mansion home—with a $330m budget that covers a new auditorium, new exhibition space and the temporary relocation since 2020 of its celebrated collection of British and European Old Masters.

Selldorf, born in Cologne in 1960, the daughter of an architect father and a designer mother, set up what is now a 70-person practice in Manhattan in 1988. After establishing herself with the New York art world, designing galleries for dealers including Michael Werner, David Zwirner and Hauser & Wirth, she won a breakout commission (1997-2001) to remodel a 1914 Carrère and Hastings mansion on Fifth Avenue for the collector Ronald Lauder, the project that became the Neue Galerie. The practice made further headlines with two high-profile private museum commissions—the new Rubell Museum in Miami Beach (2019) and a series of refurbished and remodelled buildings at Luma Arles, in southern France, for Maja Hoffmann (completed in 2018), arrayed with Frank Gehry's Art and Research Center tower. In 2022, Selldorf Architects completed a substantial remodelling and enlargement of San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art (2014-22—a project where Venturi and Scott Brown had worked in the 1990s).

As well as the Sainsbury Wing and Frick, the practice is this year working on landmark museum enlargement and remodelling projects for the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC (jointly appointed with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill), and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. With a raft of domestic commissions to add to her slate of museum work, Selldorf was profiled by Vogue magazine in August and described as “the architect of our moment”.

Architect's rendering of the entrance to the Sainsbury Wing, National Gallery, London Render: Selldorf Architects

New perspectives in the Sainsbury Wing: the ground floor

Writing in The Art Newspaper in October 2022, Gabriele Finaldi, the National Gallery's director, outlined the brief for the Sainsbury Wing as the entrance to the gallery. "One of the defining characteristics of the Sainsbury Wing is that it is entered at ground level directly from the square," he wrote. "This potent, democratic architectural gesture is consistent with the deeply embedded notion that the paintings belong to everyone and that entry to the gallery is free, and has been since the beginning ... The Prado, the Rijksmuseum, the Victoria and Albert Museum and, more recently, the Munch Museum in Oslo, have placed great emphasis on 'curating' the welcome experience for their visitors. The National Gallery needs to do the same."

Selldorf's remodelling starts with positioning the entrance so that queueing visitors can shelter in the building's loggia. Once inside, the entrance hall feels dramatically larger. Parts of the first floor have been cut away so that the hall rises to double height to east, south and west of the space, creating new views within the building, especially to and from the grand staircase.

The shop and cloakroom, formerly placed to the left as visitors came in, have been cleared away and two non-load-bearing columns have been removed, to create a long, eye-catching perspective through to the foot of Venturi and Scott Brown's monumental side-lit staircase which grows broader as it rises to the double-height main galleries on the second floor. The entrance is designed to be a stopping-off point for people to meet, an "open and empty place" where people can gather themselves and perhaps charge their mobile phones, with an espresso bar in the back.

Architect's rendering of the remodelled entrance hall of the Sainsbury Wing, National Gallery, London Render: Selldorf Architects

Gray points out the power connections where three high-specification Samsung digital screens will be installed in the entrance hall, with the largest on the back wall, showing works from the collection and potentially digital artists’ interactions with it. "The whole idea," Gray says "is that when you walk in, you know you're in an art gallery. Because we can project [images from the collection] at high resolution and we can be quite playful with them ... moving them across the three screens."

Selldorf says that she is intrigued by the appeal to passers-by of all ages of Outernet—an immersive institution with giant digital screens on five internal sides—on Tottenham Court Road, a shortish walk north of the National Gallery. “I am fascinated," Selldorf says, “because [Outernet] is... so effective. Everybody stops.” Selldorf hopes that the new large digital screens in the entrance hall of the Sainsbury Wing will help make it equally welcoming and reduce visitor anxiety at entering the historic gallery. “And,” she says, “make people curious in a different way.” The next stage, she says, would be for new visitors to find their way upstairs to the collection. "And that's what's so great about the National Gallery. You don't have to pay. You can look at art all day long. And there is no greater place to look at art."

There will be a "furniture-like reception desk" [at the centre of the hall], she says. "I wanted no reception desk, because I think it just creates authority. But we ended up with something that's a bit more low-key, and just looks like we could [move it] out of the way." Selldorf hopes visitors will "take heart" to explore further from both the open, uncluttered, welcome and from being able to see straight through the immediate wayfinding points to the rest of the museum—the foot of the main staircase and the lifts.

"People always ask why is it a curve?" Architect's rendering of the remodelled entrance hall of the Sainsbury Wing, National Gallery, London Render: Selldorf Architects

New perspectives in the Sainsbury Wing: the first floor

From the first floor landing of the grand staircase the visitor has two raking perspectives, across the first floor that features a new free-standing square-shaped, round-cornered bar, placed directly above the main entrance, and the entrance area seen from the base of the staircase. Around the first-floor area there are slightly misted glass banister rails overlooking cutaway double-height spaces on three sides. The irregular shape of the entrance front posed a challenge to Selldorf when she was designing a plan for this mezzanine-like first-floor area, which she finally expressed as a sequence of curves. "People always ask why is it a curve? I'm not an irrational person. But Venturi was to some extent, and the structure [of the angled entrance front] is very irrational. So when you look at the [entrance] structure [from the first floor], it's impossible to make an angular shape and let it make sense. And so .... I sketched, sketched, sketched and then at some point I was like, 'You're just gonna have to follow the structure.' And that's what this is."

"The thought that anybody would come here, run up the stairs and meet their friend for lunch is so wonderful," Selldorf says, standing in the first-floor bar area. "But also downstairs you can have a coffee or just sit there. You don't have to buy something." The double-height spaces on three sides of the bar area are enhanced by the light from the west side of the building let in by a wall of glass that has been revealed by removing two rarely used meeting rooms, leaving one large meeting or function room at the north end of the glazed west wall. From the first floor a visitor can see passage ways on either side of the building leading from Trafalgar Square to Leicester Square, two of the busiest tourist areas in the city. To the west is Whitcomb Street, open to traffic and pedestrians, and to the east, overlooked by the main staircase, and running under the second-floor bridge linking the Sainsbury Wing to the Wilkins building, is the pedestrianised Jubilee Walk.

"This is new public realm": Selldorf's rendering of the Sainsbury Wing entrance (left) and the Wilkins building (right), separated by Jubilee Walk. A link from Trafalgar Square to Leicester Square to the north Rendering: Selldorf Architects

"We've got big ambitions to connect two of the greatest squares in the world," Gray says. Whitcomb Street and Jubliee Walk are "like a bridge", Selldorf says. "A strange intersection in London" of a grand square with small side streets. "I think it's great that you can see that ... all at the same time," she says. Referring to these areas and the new "square within the square" next to the Wilkins building, Gray says that he hopes that over time the gallery will "start to programme for this space, because this is new public realm—as Annabelle said, it was never here before. So this is really public give-back."

From the first floor, Selldorf points out the view into the Wilkins building and the rooms where the new research centre is being created—an "intellectual engine of the National Gallery", as Finaldi has said, "which aims to be the prime resource in the UK for the study of Western European painting from the Middle Ages to the 20th century". "That’s the next phase of the renovation that we're working on right now," Selldorf says. "And to me it's very exciting that there is visible connection to scholarship."

Selldorf's feel for materials and materiality

Selldorf is thoughtful, soft-spoken and confiding in person. During the site tour she makes detailed, acute, references to colour: the green Purbeck marble used in the ground-floor espresso bar, the pietra serena—the blue-grey Florentine stone used for the 1991 columns in the second-floor galleries and now brought down for continuity to embellish the columns in the entrance hall—even the strong colouring acquired by an elegantly patterned veneer from the footfall of the workforce walking on plywood sheeting on their way in and out of one of the building's lifts. "I love stone," she says. "I spent a lot of time thinking about what is the right stone," for the ground-floor paving. "I thought it should be York stone, because I wanted to take the pavement from the outside inside. And then we realised that it just wasn't quite working. We couldn't make the pattern the same on the outside as on the inside."

Annabelle Selldorf Photograph: Harry Mitchell

Selldorf surprised by hostility to Sainsbury Wing plans

Selldorf has nearly four decades' experience of public reactions to her architectural proposals, many of them for alterations or additions to beloved public museums or galleries. But nothing, it is clear, prepared her for the level of criticism addressed to her proposed alterations to Sainsbury Wing, a protected Grade 1 building, when they were submitted to Westminster Council for approval in the autumn of 2022.

The criticisms "were so nasty," Selldorf says. "That surprised me."

"I really think that we all approached [the Sainsbury Wing project] with so much consideration and respect and to ... encounter this kind of vitriol. I thought that was very hard. That was the hardest that I've experienced. We have to make presentations to the public all the time, and nobody is shy of saying what they want to think. But this was a little different. This was ... really not very nice."

Selldorf felt supported at the time, she says, "by the extraordinarily positive relations that we all have" on the Sainsbury Wing project. Finaldi and Gray, she says, "have been nothing but supportive, as has the board. And the backers." Of those backers, Timothy Sainsbury, the survivor of the three Sainsbury brothers, the heirs to Britain's leading supermarket chain who had entirely funded the building of the wing in 1986-91, wrote an open letter to The Art Newspaper in November 2022 saying that the original donors backed the Selldorf proposal and the need to make functional changes to the building. Timothy Sainsbury's Headley Trust and the Linbury Trust, founded by John Sainsbury (who died in 2022) and his wife Anya Linden, have led the Sainsbury family in providing the largest contribution to the cost of remodelling the wing that they first paid for more than 30 years ago.

Part of the bitterest criticism levelled at Selldorf in October and November 2022 had related to plans to remove two non-load-bearing columns from the entrance hall with the aim of uncluttering the space and provide a view through to the stairs and lift. This, critics of the proposal said, would destroy the atmosphere created by Venturi and Scott Brown in 1991, where the visitor moved from the darker, low-ceilinged crypt-like entrance to the light-filled staircase and on up to the lofty top-lit galleries on the second floor. It was an approach, Scott Brown told The Art Newspaper in August 2024, inspired by the architect John Soane's "cross-section of Dulwich [Picture Gallery]". The low ceiling, Scott Brown said, "leads to the contrast of the big staircase with its public, light-filled view, a lesson learnt from [the architect Edwin] Lutyens."

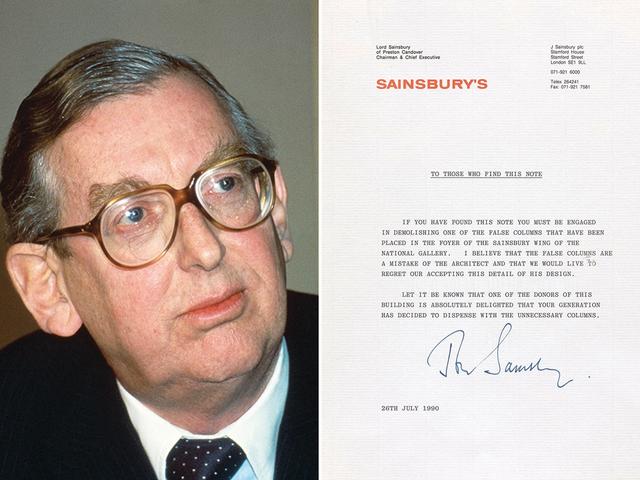

It was therefore all the sweeter for Selldorf when, in August 2024, The Art Newspaper published a letter from John Sainsbury, left as a time capsule in one of the non-load-bearing columns in 1990, in which he said he felt the two "false columns" had been a mistake of the architect.

The letter of 26 July 1990 was addressed “To those who find this note”—who turned out to be demolition workers tasked with removing the column. The note, typed in capital letters, and now in the archive of the National Gallery, reads:

IF YOU HAVE FOUND THIS NOTE YOU MUST BE ENGAGED IN DEMOLISHING ONE OF THE FALSE COLUMNS THAT HAVE BEEN PLACED IN THE FOYER OF THE SAINSBURY WING OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY. I BELIEVE THAT THE FALSE COLUMNS ARE A MISTAKE OF THE ARCHITECT AND THAT WE WOULD LIVE TO REGRET OUR ACCEPTING THIS DETAIL OF HIS DESIGN.

LET IT BE KNOWN THAT ONE OF THE DONORS OF THIS BUILDING IS ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED THAT YOUR GENERATION HAS DECIDED TO DISPENSE WITH THE UNNECESSARY COLUMNS.

"And then when that letter story came out," Selldorf says. "I have never received as many emails as I did on the heels of that. People were so amused, so I said, 'that's just wonderful' ... in a way those things make up for it."

Learning to love postmodernism

The project has been particularly interesting for her as an architect, Selldorf says, "because postmodernist architecture is not my territory. It was a learning experience to understand it. And in understanding it, being not only respectful, but to some extent paying homage to it."

As Selldorf put it when she gave the annual Linbury Lecture for the National Gallery in December 2023, she has always hoped that, for all the considerable changes to the Sainsbury Wing, the remodelled building "will look like and feel like the Venturi building that it always was". And that it will "be the building it always wanted to be".

It may be that Selldorf—so bitterly criticised in 2022 by the self-declared protectors of Venturi and Scott Brown’s postmodern vision—will, through the thoughtful clearing, recasting and uplifting of materials and spaces in the Trafalgar Square building, both bring it gently into the 21st century and, at the same time, be seen to shine fresh light on the original architects' most profound and telling architectural gestures.

The over-riding goals of the project, she says, have been bringing materials together that draw both the square outside and the Wilkins building into the Sainsbury Wing, all the while "thinking about how people move in space, what people's needs are, and stitching it all together. And... of course while you're doing it, you have to forge ahead and solve problems [on the go]."

"A lot of hard thinking went into it," she says. "And so it's so rewarding to feel that it's actually paid off... I love this project."