In the weeks leading up to this Miami Art Week, a WhatsApp chat was abuzz with opportunities for locals. “In exchange for complimentary Art Basel VIP tickets, [a gallery] is seeking volunteers to help set up a 39 foot [...] paper artwork,” a person in the chat posted.

The offer of access to one of the world’s biggest art fairs in exchange for some physical labour—typical of the Miami Art Week gig economy, artists say—was no doubt appealing to Miami-based artists, so many of whom are being rapidly priced out of their homes and studios. Entry into the fair’s VIP preview promises access to collectors and dealers.

Miami’s art scene is known for its grassroots vibrancy, especially every December during Art Basel in Miami Beach, when the city takes the spotlight on the art-world stage. But despite the thousands of collectors and gallerists making deals in the city, many Miami-based artists face financial and systemic challenges that have not been documented in any rigorous way. The Miami Artist Census, launched by a group of local artists, hopes to change that by surveying the city’s creative class to collect data that will give them a stronger voice in their communities and beyond.

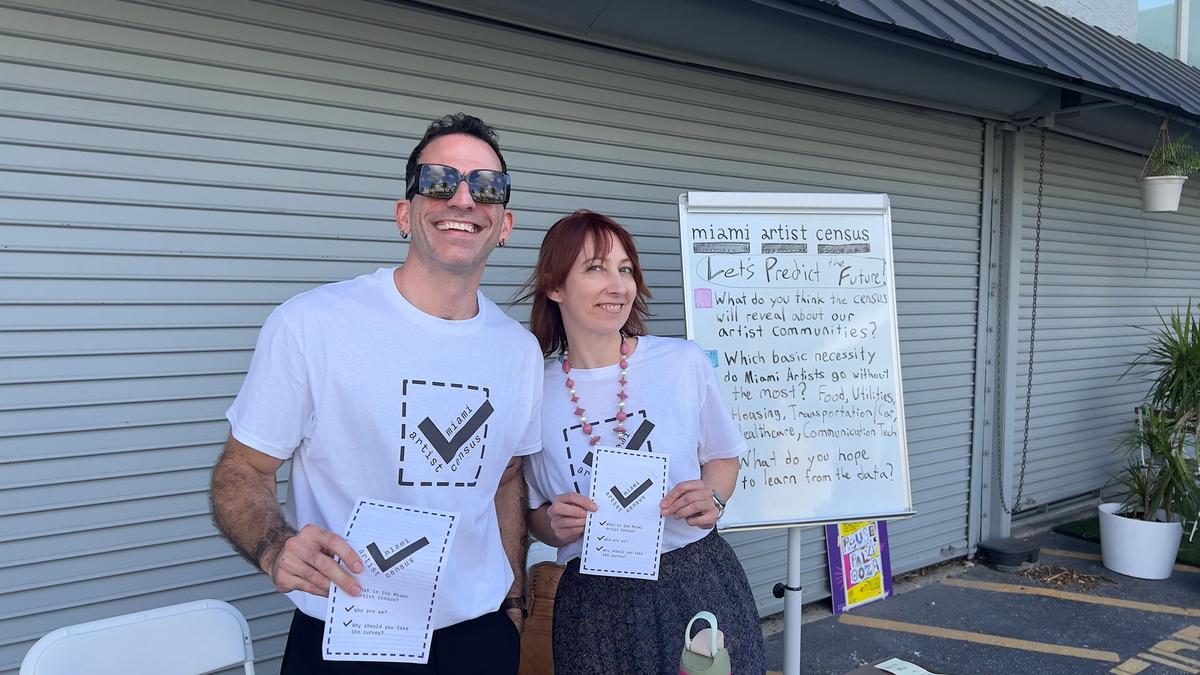

The census grew out of the collective Artists for Artists: Miami and launched in October 2023. The project is led by several core members including misael soto, Carrie Sieh and others.

“The census has really taken on its own identity, with its own budget and its own social channels,” soto says. The census seeks to gather quantitative data on the lived experiences of artists in the Miami-Dade area. With a goal of reaching 1,000 responses by 31 December, it already has around 450 participants. The initiative has received support through grassroots volunteer efforts and a modest anonymous donation.

“We’re pushing into schools, art departments and local art centres in Miami-Dade,” Sieh says. “This is by artists, because it’s for artists. That’s been our mission since day one.”

The inspiration for the census came from a series of meetings held in early 2023, where local artists came together to discuss shared struggles and possible solutions. As the conversations progressed, participants recognised the need for a clearer understanding of the shared challenges of artists across the region.

“We found ourselves talking a lot about what we needed individually, and we realised we were lacking a broader understanding,” soto says. The group then turned to examples of artist censuses in cities like Los Angeles and Chicago, finding valuable guidance from initiatives such as the Los Angeles Artist Census, led by Tatiana Vahan, who shared her insights on how data could empower artists to advocate for better conditions.

In the summer of 2022, soto participated in Heat Exchange with Bas Fisher Invitational, in which a group of Miami artists travelled to Stavanger, Norway, to engage with the artist community there. A recurring topic was forming an artists’ union in the US similar to those that have existed in Norway for around 200 years.

“Before Norway was oil rich, it had 150 years of artists’ unionising efforts,” says Lee Pivnik, a member of Artists for Artists: Miami who helped beta test the census. “When they became oil rich, the artists had a unified voice and power to go to the government and say, ‘We want grants that are ten years long, and we want programmes that are like this,’ and they got it.”

Information on the census is being provided to schools, art departments and local art centres

Photo by Alexandra Martinez

Actionable snapshot

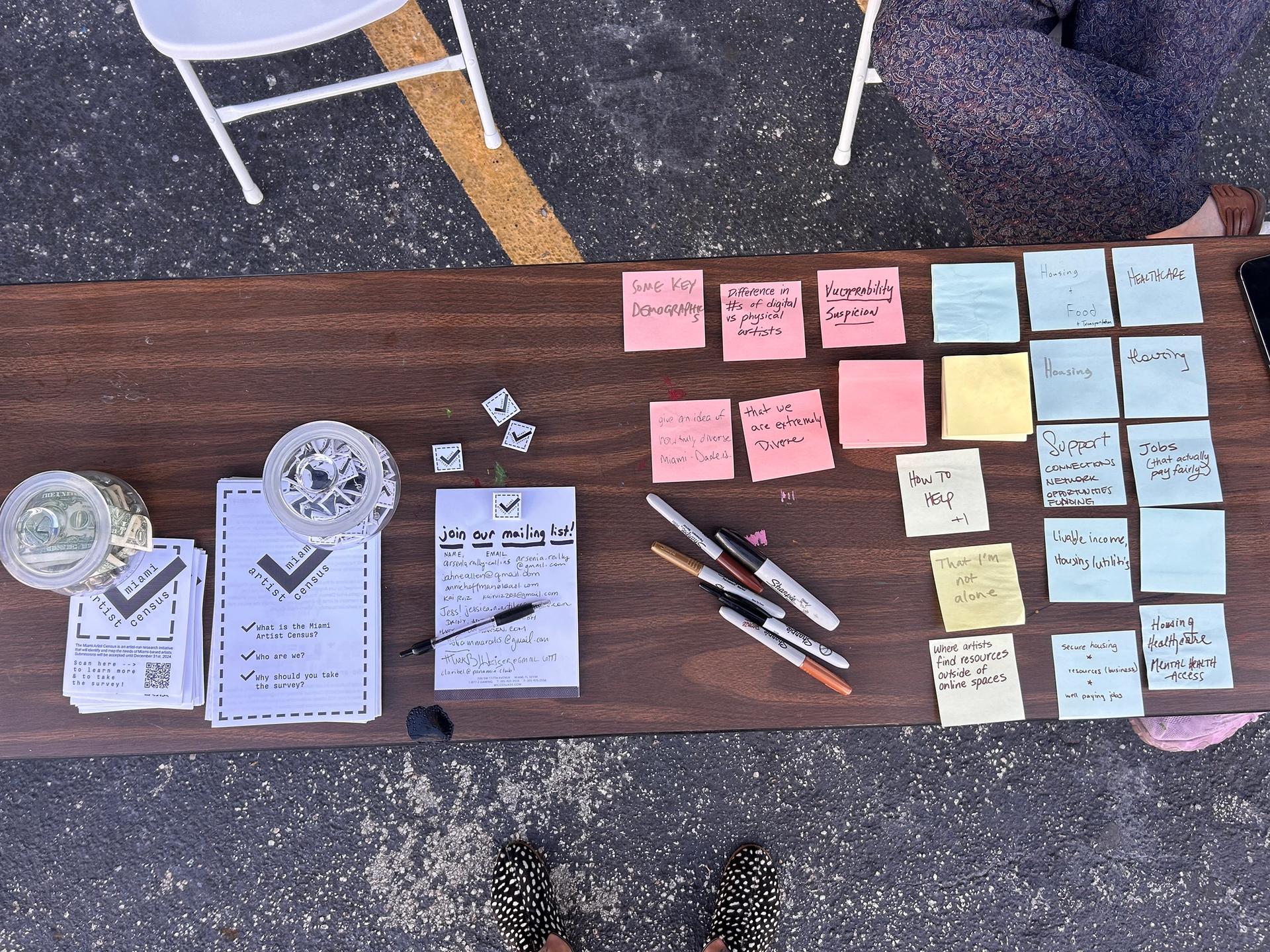

The Miami Artist Census was designed to create an actionable snapshot of Miami’s art community, covering areas such as income, healthcare, housing and expenses like caring for children and other dependants. “I know artists who’ve nearly turned down prestigious residencies because they’re the primary caregiver for a family member,” Sieh says. “This is a structural issue that the art world often overlooks.”

While major cultural institutions regularly collect data on artists, the creators of this census felt that there was a need for a survey that was directly responsive to the artist’s experience. According to soto, existing surveys by larger organisations often operate “in the service of [the institution’s] mission, and artists can come out of those feeling a little extracted from, which is par for the course of the life of an artist”.

According to Sieh, one of the first pressing issues that the census group identified was inadequate compensation. Many artists struggle to make a sustainable income from their work, facing challenges in receiving fair payment—or, in some cases, any payment at all—from art institutions and galleries. One of Artists for Artists: Miami’s first efforts was to help some of its members negotiate payments from a local arts organisation for an exhibition.

“Artists’ financial situations and compensation were the first things we looked at, but we knew there was much more to address,” Sieh says.

According to soto, the high costs of studio spaces and other resources are another significant set of issues, especially in a rapidly developing city like Miami. “I’m a conceptual artist, so a lot of my work is done on my laptop, but many others depend on access to specialised tools or studios, and the cost of that space is through the roof,” soto says.

The census team hopes to shed light on these financial and spatial challenges by asking targeted questions. For instance, the census includes questions about how often artists donate works to institutions, an issue that has rarely been documented in any meaningful way. “There can be a lot of pressure, especially on younger artists, to donate pieces to established institutions for visibility,” Sieh says. “But that’s a significant financial loss for them in both time and materials, which may not always pay off professionally.”

The Miami Artist Census draws heavily on the approach used by the Los Angeles Artist Census but has been tailored to Miami’s unique conditions. Organisers emphasise the importance of transparency in an industry where artists often rely on word-of-mouth to gauge how fair or reliable a given institution or opportunity may be. “We want to have data to back up what’s often just gossip or anecdotal,” soto says.

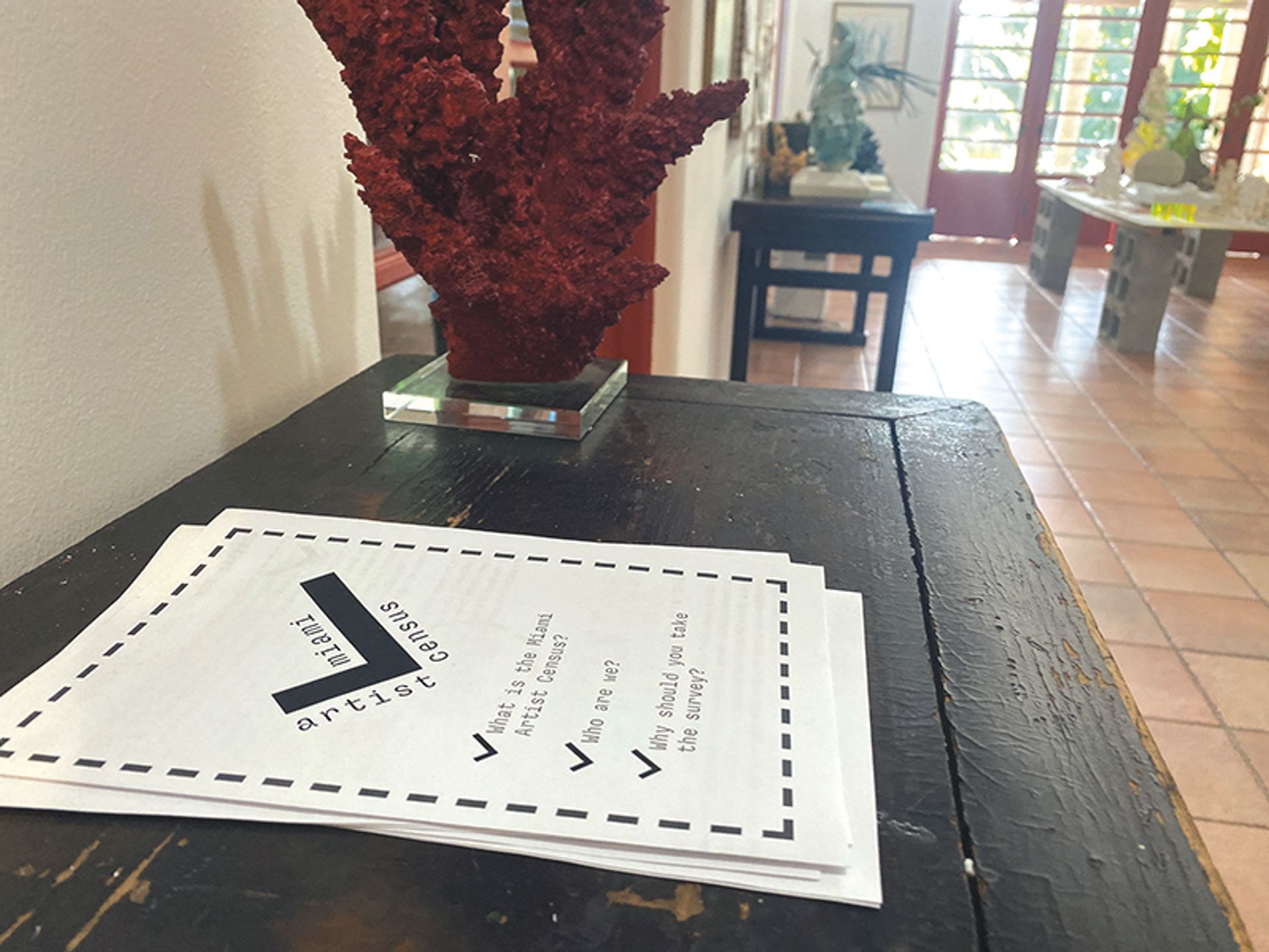

Since its launch in October 2023, the Miami Artist Census has attracted 450 participants; organisers are aiming for 1,000 responses by the end of this year

Courtesy Miami Artist Census

Constructive dialogue

While the census provides a space to document challenges, the organisers hope it will also collect data on what works well for Miami artists. Sieh and soto hope to use the results to engage institutions, policymakers and funders in constructive dialogue about the art community’s needs.

“We want to empower and build solidarity among artists here in Miami,” Sieh says. “This is, first and foremost, about lifting up our community and putting concrete numbers to what many of us already feel and know about being an artist in Miami.”

The questions are intentionally broad, phrased and presented in a format designed to make artists feel welcome. The organisers are hoping to reach a wide range of respondents in terms of career stages, from emerging artists or established practitioners. Inclusivity was central to the approach, soto says: “We spent a lot of time considering: How is this going to be heard? Who’s going to feel like they’re seen here? We’ve already had feedback from some survey-takers that it feels empowering just to take it.”

To keep the census manageable, the team focused primarily on quantitative data, with a total of 93 questions, although most participants answer around 60.

“We wanted the data to be solid, but we also didn’t want to overwhelm people,” soto says. “We’ll likely have a second survey in the future to explore more personal, existential questions.”

The project will unfold in stages, with a first report scheduled for March 2025. Smaller, thematic reports will follow, exploring critical issues such as housing, healthcare and employment. There is also a plan to release an interactive online dashboard, where the public can explore the aggregated data.

The census organisers are running several community-engagement events, including one that took place at Soho House in late November. Another is scheduled for the Untitled Art fair (8 December at noon) and will become part of the fair’s podcast series.

In the longer term, the Miami Artist Census organisers hope to create a ripple effect by equipping artists with concrete data that they can use when negotiating opportunities, both locally and internationally. Sieh points to a recurring scenario in which international galleries approach Miami artists, asking to show their work without any upfront payment.

“We hope this data will help artists know their worth and feel empowered to advocate for themselves,” she says. “Maybe that will lead to more ‘no’s to exploitative offers, creating a stronger local scene where artists can sustain themselves.”

For Miami’s art community, the census has the potential to shift the landscape in meaningful ways, creating both an archive of the current moment and a pathway towards a stronger, more cohesive art scene. For now, Sieh and soto hope the community feels their efforts are working towards a shared goal.

“This census is a step towards transforming what has always been artist-to-artist gossip into reliable information,” soto says. “With facts, we can finally address these issues directly.”