The British-Mexican Surrealist Leonora Carrington shot to the top tier of the global art market in May when Sotheby’s New York sold her fantastical 1945 tempera painting Les Distractions de Dagobert to the Argentinian property magnate and museum founder Eduardo Constantini for a record $28.5m. The sale propelled Carrington far beyond her previous Sotheby’s record of $3.3m only two years earlier, crowning her the most valuable female British artist at auction.

Institutional interest had already been surging since the artist’s death in 2011, aged 94. Curator Cecilia Alemani’s 2022 Venice Biennale exhibition The Milk of Dreams took inspiration from the otherworldly fairytales Carrington invented for her children in the 1950s. A stream of major museum retrospectives—in Ireland, the UK, Mexico, Spain and Denmark—is due to continue next year at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University in Massachusetts and Milan’s Palazzo Reale.

It is in this febrile context that the “last sculptures” from Carrington’s estate are being introduced to European markets and audiences for the first time, igniting a heated debate among experts over their authorship and place in the artist’s legacy.

El Bailarín (the dancer, 2011), a monumental bronze with a bird’s head and plumage, led the way when it popped up in Basel’s Theaterplatz during Art Basel in June. The same figure stood in Regent’s Park as part of Frieze London’s outdoor sculpture show in October.

El Bailarín (2011) was part of Frieze Sculpture 2024 in London this month Presented by Rossogranada; Photo: Linda Nylind; Courtesy of Linda Nylind/Frieze

Smaller-scale bronze creatures and a wall of 25 masks were displayed alongside drawings, tapestries, lithographs, theatre costumes and jewellery in Leonora Carrington: Rebel Visionary (12 July-26 October), an ambitious selling exhibition at Newlands House Gallery in Petworth, Sussex (which included works on loan from private collections that were not for sale). Similar bronzes and jewellery pieces featured this autumn in commercial group shows at Galerie Krinzinger in Vienna and at Paris galleries including Galerie Raphaël Durazzo, Forma and La Boulangerie! as well as at the non-profit Frac Corsica.

Price tags of up to €400,000

The flurry of initiatives is organised by Rossogranada, a Zurich-based art startup that has exclusive representation in Europe, Switzerland and the UK of the Consejo Leonora Carrington (Leonora Carrington council), established in Mexico by the artist’s younger son, Pablo Weisz Carrington. Revenues from Rossogranada’s private sales of works from the Consejo and other consigned pieces, from Impressionism to contemporary, support its hybrid role as a funder of contemporary artistic production, residencies, publications and research, says the firm’s founder and chief executive officer, Valeria Diaz Granada. Prices for the bronze sculptures range from €85,000 to €400,000 and several have sold. All of them come with certificates of authenticity issued by the Consejo, signed by Pablo. In partnership with the platform Vaultik, Rossogranada is also offering its clients blockchain-based digital certification.

“Our goal is to foster a deeper understanding of Carrington’s work, regardless of the exhibition type, by integrating robust programming such as publications, lectures and community events that expand on her artistic themes,” Diaz Granada says. Rossogranada is publishing a journal of essays edited by Clothilde Morette, the artistic director of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris. El Bailarín and another 2011 sculpture, La Inventora del Atole, are due to be included in the institutional touring exhibition Forbidden Territories: 100 Years of Surreal Landscapes, opening on 23 November at the Hepworth Wakefield in West Yorkshire, then travelling to The Box in Plymouth and Museum Arnhem in the Netherlands.

But among experts of Carrington’s work, the Consejo’s editioned bronzes have raised doubts about their attribution, with the collector and curator Viktor Wynd describing the Newlands House Gallery exhibition as “an abomination” in the London Review of Books.

Most of the Consejo Leonora Carrington bronzes are dated to 2008-11, when the nonagenarian artist was unable to paint due to arthritis. Since 2017, the council has placed 82 bronzes on long loans to two government-funded museums dedicated to the artist in San Luis Potosí and Xilitla, Mexico, and organised pop-up exhibitions across the country, some of them commercial. According to the San Luis Potosí museum’s website, Carrington was encouraged by Pablo to collaborate with the foundry of Alejandro Velasco, which produced 42 sculptures from 2008 to 2011; she also created 17 pieces with the workshop of José Sacal and a further three with José y Miguel Ángel Rivero during the same period.

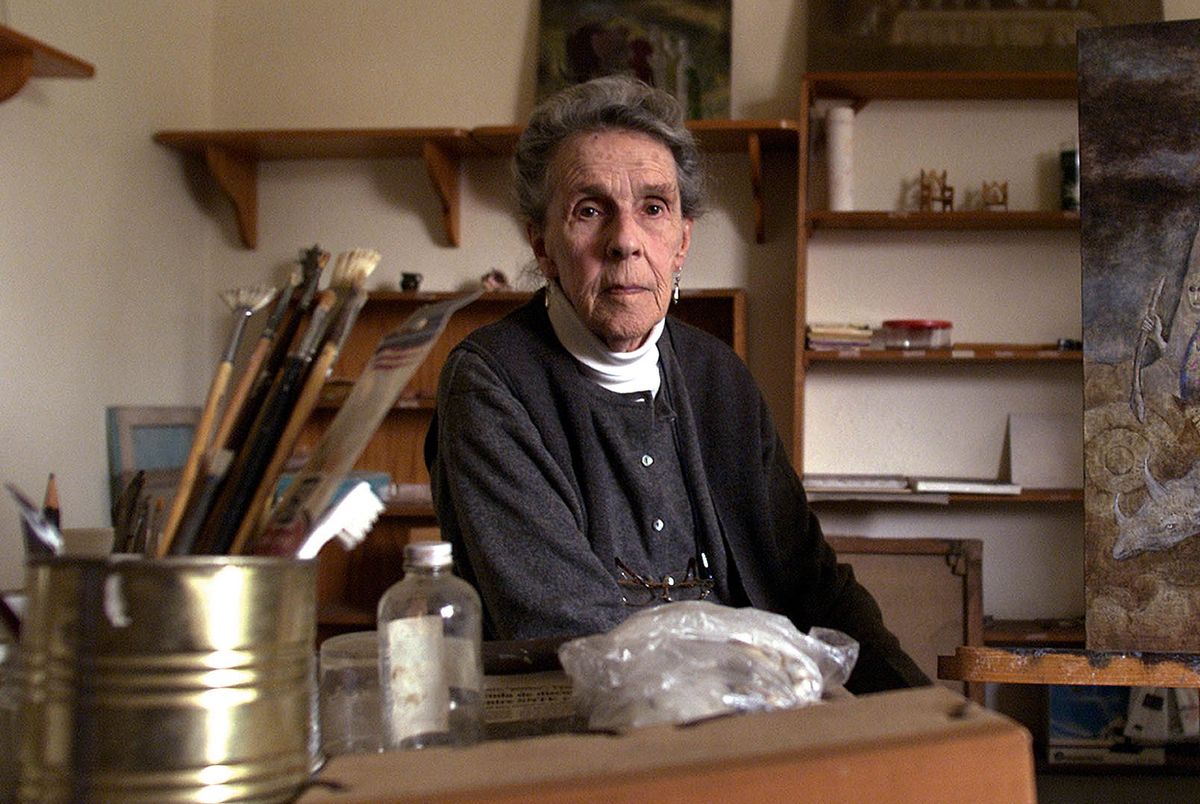

Leonora Carrington with a model for Camaleon (2010) Image: courtesy of Rossogranada and the Consejo Leonora Carrington

Pablo, a pathologist and artist, donated 45 sculptures to the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana in Mexico City (UAM) and sold the institution the house in Mexico City where his mother lived and worked for more than 60 years, on the condition that it be converted into a public museum. (The opening now appears to have stalled due to a labour dispute between UAM authorities and the university union.) According to an interview in the university’s magazine in 2017, Pablo suggested to Carrington that she continue working into her 90s on an “exclusive” collection of new sculptures as a form of financial security, so they “could be sold to cover medical expenses” if necessary. Photographs, published by the Consejo and shared with The Art Newspaper, document her examining the full-scale models at home or in the foundry, often accompanied by Pablo and the fabricators.

Meanwhile, Carrington’s elder son Gabriel Weisz Carrington, a writer and academic, has criticised “bronze monstrosities” sold and displayed in Mexico by “swindlers who tried but never succeeded in recreating her skill”, as he wrote in a 2021 memoir of his mother, The Invisible Painting. “The few sculptures she did create display elegance and artistic balance, qualities that are entirely lacking in these vulgar heaps of bronze, devoid of imagination as they are.”

In an interview with the Mexican newspaper El Universal to mark the launch of his separate Fundación Leonora Carrington in 2015, Gabriel spoke out against counterfeit sculptures: “There are workshops run by dishonest people; there is counterfeiting because, at a given moment, the moulds were not destroyed and there were also certificates endorsing the work.” His foundation, which previously announced a cataloguing initiative to safeguard the artist’s work, says it does not issue certificates of authenticity.

The Consejo Leonora Carrington’s co-founder and president, Fermín Llamazares, rejects Gabriel’s past criticism as “false allegations” that “demean and damage his mother’s legacy”. Llamazares adds: “All the bronze sculptures made by Leonora that Mr Gabriel attacks were done in the late years of Leonora’s life. There are photographs and video footage of her working on the pieces. All the work is also copyrighted and in a catalogue.” In an essay for the Consejo’s 2017 catalogue, Black Book, Llamazares describes Carrington’s development of the bronzes from 2008 to 2011, first “sketching, tracing and enhancing the images that were then converted by her into plasticine models”. The models were enlarged and remodelled by the workshop, he writes, then “Leonora supervised and corrected each enlarged model before proceeding to casting in bronze.”

The sharp divide between the brothers and their foundations has not helped to clarify the “fuzzy situation in terms of authorship and manufacturing” surrounding almost all of Carrington’s late bronzes, says Axel Stein, an art adviser and former head of Latin American art at Sotheby’s. The auction house “preferred to abstain” from selling her sculptures during his tenure there, he says, to avoid “leading people into obscure and uncharted territories”. (In May this year Sotheby’s sold one Carrington bronze, conceived and cast in 1994, that was authenticated by Gabriel and accompanied by a certificate signed by Carrington herself.) Stein adds: “There are so many options in the market to buy other work that was clearly made by the artist, that maybe people don’t need to buy [sculptures] that are not particularly attractive on top of that.”

A garage full of works

The San Francisco art dealer Wendi Norris, who began working with Carrington in 2004 and has sold or marketed nearly 600 works by her, says she “did not see any work in progress or evidence of these large-scale bronzes” during multiple visits to her home and studio. However, Carrington’s biographer and cousin Joanna Moorhead wrote in the Consejo’s 2017 catalogue that the artist was “sculpting” when they met in 2006: “The garage of her house was full of works in progress, and every so often someone came to assist her and then maquettes would be taken off to the foundry for casting.”

Norris says: “I concur with Mr Wynd that most people who have a deeper understanding of Leonora’s work refuse to present these bronzes in question. It is essential to note that like many deceased artists, there is no single entity or set of scholars that has been solely vested with executing her vision, but clearly her heirs have inherited certain rights.” Asked whether Carrington could have made the works for financial reasons, Norris says: “As far as I understand, she did not personally have a financial imperative to make new sculptures.”

Carrington’s popular monument How Doth the Little Crocodile installed on Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City Photo: Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble; © Estate of Leonora Carrington/ARS, NY and DACS, 2024 London

The uncertain status of the post-2008 bronzes is complicated by the fact that Carrington was exhibiting large-scale sculptures in bronze in Mexico City from 1999 until her death via a series of public art projects promoted by her dentist and friend, Isaac Masri, an editions publisher and founder of a cultural centre. Smaller versions of some of those works are visible in historic video footage of Carrington’s home, and they entered the market through local galleries. She donated How Doth the Little Crocodile (2000), a five-ton boat of crocodiles inspired by a Lewis Carroll poem, to Mexico City, where it remains a crowd-pleasing monument on Paseo de la Reforma.

Masri recalls the challenge of inviting Carrington to participate in Libertad en Bronce (freedom in bronze), the first of several public sculpture exhibitions he organised on the Reforma; she “reluctantly accepted” dental wax and instruments he brought her as modelling materials. It was Masri who first engaged the Velasco foundry to scale up the artist’s small maquettes into bronze, which he says were limited to editions of six plus an artist’s proof and editor’s proof, while the monumental pieces were unique.

Masri argues that only the Velasco editions bearing certificates from his publishing house, Impronta Editores, “signed and numbered by me and by the artist”, can be considered Carrington’s authentic lifetime work in bronze. He contends that Carrington’s later bronzes were created from 10cm models she made under “pressure” from Pablo—at a time when “Leonora told me that she felt tired and had no desire to work”—and that the editions were not controlled.

Visual analysis suggests that some of the Masri bronzes were copied later with different titles and dimensions. The Newlands House Gallery exhibition included Cumunus Mask (2010) from an edition of four, a smaller version of Masri’s edition Corrunus (1995), which was itself based on a 1960s sculpture of a Celtic god that Carrington originally fashioned in concrete with steel mesh. (The Consejo Leonora Carrington also owns a 2011 version in silver alloy covered in gold leaf.) Moon Sun (Luna Sol) (2010) is a later, smaller version of Lion Moon (Luna León) (1995), cast for the first Masri collection from a 1970 concrete prototype.

Gallery and auction sales listings online, aggregated by Artsy, also show that different editions exist of certain late Carrington sculptures, all apparently accompanied by a certificate of authenticity. The Ship of Cranes, which resembles the Crocodile vessel with bird figures, has been traded in two editions of 20 (one 58cm long with a white-and-black patina; one grey and 60cm long) and another of 500 (with a white patina, 15.5cm long), with dates ranging from 2008 to 2011. The Consejo’s catalogue includes only a 2010 edition of ten, over a metre long, which is displayed in a fountain outside the museum in San Luis Potosí. The sculpture has also been advertised with the title The Ship of Craner by two commercial galleries in Mexico and one in Colombia.

Fermín Llamazares says that the Consejo sculptures are numbered, certified and clearly presented as editions, and not as unique works. “There are several motifs that were made in different sizes in exact numbered series,” he says.

Aesthetic inconsistencies

Several leading art historians who spoke with The Art Newspaper raised concerns about the attribution of the late sculptures to Carrington, not only because of their uncertain editioning and collaborative fabrication at the end of her life, but because of aesthetic inconsistencies they perceive between the bronzes and Carrington’s wider artistic output.

One scholar, who requested anonymity, says Carrington “was never really dedicated to sculpture; that was very, very rare”. Earlier in her career, she painted wooden objects carved by her friend José Horna, such as a cradle made in 1949 to celebrate the birth of his daughter Norah, and Cat Woman (La Grande Dame) (1951), a standing figure with a mask-like face, owned by her patron Edward James. In the 1970s and 90s, she developed silver editions with the Mexican jewellery brand Tane.

The scholar believes it is “impossible” that Carrington personally “contributed to this enormous amount of work while she was almost at the hospital in the last year of her life”. Moreover, the late sculptures are “not really creating anything new”, since the majority depict hybrid figures and creatures quoted directly from the artist’s past works of painting. For instance, El Bailarín comes from a 1954 painting of the same name, while Woman with Fox (2010) represents a seated figure in the oil on canvas Nine Nine Nine (1948).

Diaz Granada of Rossogranada says, even in her 90s, Carrington was “as involved as physically possible” in the production of the bronzes and “had the presence of mind to produce the work she did”. She adds: “Academic research is behind when it comes to the late-period Carrington works, mainly due to the fact that the archives are only now being organised, that the [Consejo] is very young and that Western academia hasn’t yet dedicated time and resources to access and study the material in Mexico.”

The cultural historian and writer Marina Warner, who spent time with the artist in the 1980s when she lived in New York, notes that Carrington “made work in different media”, for instance in her designs for theatre sets and costumes as well as her writings. But the late sculptures “look like enlarged approximations”, she says, lacking the delicate style and “densely imagined” approach of Carrington’s visionary paintings in oil and tempera, which were informed by Renaissance predellas and Hieronymus Bosch, as well as her “strange register that was both spiritual and comic”.

Dawn Ades, a specialist of Latin American art and Surrealism, also characterises Carrington as “fundamentally a painter of great subtlety”. Her primary legacy lies in the paintings and the writings, Ades believes. “I am very uncomfortable with the current promotion of these bronzes all over the place as if it’s a marvellous resurgence in old age with a new medium.”

An anonymous curator likens the bronzes to museum merchandise that reproduces artists’ imagery as a form of branding: “I have nothing against that, but you wouldn’t be able to sell it as an authentic work of art.” They point to the Consejo’s 2011 lithographs, which replicate paintings from the artist’s prime period in the late 1940s and early 50s in editions of 100, priced at €8,200 and upwards, as a further example of collectibles “created for the market”.

Leonora Carrington's El Sueño del Fuego (2008) is on show at the Galerie Raphaël Durazzo in Paris Image: © Francois Rouzioux

The late sculptures do, however, have their defenders. “I am surprised that one can vilify a work with such confidence without the slightest proof, testimony or compelling argument to oppose archival photos and numerous interviews of [Carrington] in her later years,” comments the dealer Raphaël Durazzo in response to Viktor Wynd’s article. “Have we ever heard this about [Max] Ernst’s late works, for example? Do we find fault when we see them exhibited? It took decades to put the work of these women [Surrealists] in its rightful place… now we are also going to be surprised that they are capable of sculpting in plasticine because they are old?”

Durazzo dates Carrington’s involvement with sculpture to her early 20s in 1939, when she made plasters while living in rural France with her lover, Max Ernst, who introduced her to the Surrealist circle. Durazzo says the artist produced sculptures throughout her career, particularly from the late 1980s onwards.

Alyce Mahon, professor of Modern and contemporary art history at the University of Cambridge, guest-curated the Durazzo gallery’s all-women show, Surrealism in the service of distraction (until 23 November), as part of the centennial celebrations of Surrealism by the Paris-based Comité des Galeries d’Art. Four bronzes and an array of jewellery from the Consejo Leonora Carrington, alongside one painting Composition (Ur of the Chaldees) (1950), previously in the collection of Edward James, are on view with works by fellow Surrealists Leonor Fini and Dorothea Tanning, and the contemporary painters Sara Anstis, Piper Bangs and Ginny Casey.

“There’s still a huge amount to be discovered around Surrealism, including the work of women globally and aspects of Carrington’s body of art,” Mahon says. She interprets the three historical artists in the show as “an avant-garde sorority” who all experimented with different media beyond painting. She notes they all had romantic relationships with Ernst and that he was a painter who also sculpted and made jewellery—but states it is the idea of “distracting Surrealism from the male-centric narrative” that underpinned her curation. A specialist in Tanning’s sculptures, Mahon says, “the sculpture of women Surrealists has always interested me, and the public element of sculpture as seen in Carrington’s How Doth the Little Crocodile and other works in Mexico City is something that we don’t often see with women. Its important we consider complementary iconography and aesthetics across painting, drawing, design and sculpture in Surrealism, and for me that merited closer attention and informed my selection of Carrington’s works for this show.”

Indeed, many male painters, including other prominent Surrealists such as Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, are recognised for also making bronze sculptures. The inherently multiple nature of the casting process, however, poses considerable challenges for the marketplace in bringing order to the editions and for scholars seeking to assess the extent of an artist’s creative involvement. A number of legal battles have played out over the legitimacy of posthumous bronzes attributed to artists including Rodin, Renoir and Giacometti.

Challenges for the marketplace

“Authenticity is an elastic concept in the world of sculpture,” explains Patrick Elliott, the chief curator of Modern and contemporary art at the National Galleries of Scotland and an expert in 20th-century French sculpture. While lifetime casts made under an artist’s supervision are prized, legally authentic bronzes can be cast well after the artist’s death by their estates and other rights holders. French law defines a limited edition of eight plus four artist’s proofs as an original work of art; any other reproductions must be clearly designated as such. This system, Elliott says, has been widely adopted in the European art market. The market also depends on “full disclosure” about the production and numbering of such editions.

As opinions on the subject seem so deeply polarised, the case of Carrington’s late bronzes remains as surreal as her art.