Nicola L. was born in April 1932 and grew up in a conservative French family in the coastal city of Mazagan, Morocco. “I was a rebel in everything,” she later said, “my father never liked the idea of his daughter becoming an artist.” In 1949, the family moved to rural France (her father was a commander in the calvary and relocated frequently) and she began drawing landscapes in gouache. Shortly after this, in 1950, she enrolled at the Académie Julian in Paris and devoted herself to abstraction during her late 20s.

Amid the fervour for Nouveau Réalisme, and summers in Ibiza, the idea to experiment with another medium emerged. She was influenced by the work of the Argentine proto-conceptualist Alberto Greco, who had come up with Vivo-Dito—a manifesto for art that championed chance and living in the now. “He was a life-actor, his life was his art,” L. later explained. “I wanted to oblige people to participate.” This influence led to her loosely hanging canvas rectangles, a series of “paintings” that the critic Pierre Restany called Pénétrables. Here, spectators could penetrate the canvases with different body parts so that they would protrude from the picture plane like a new skin.

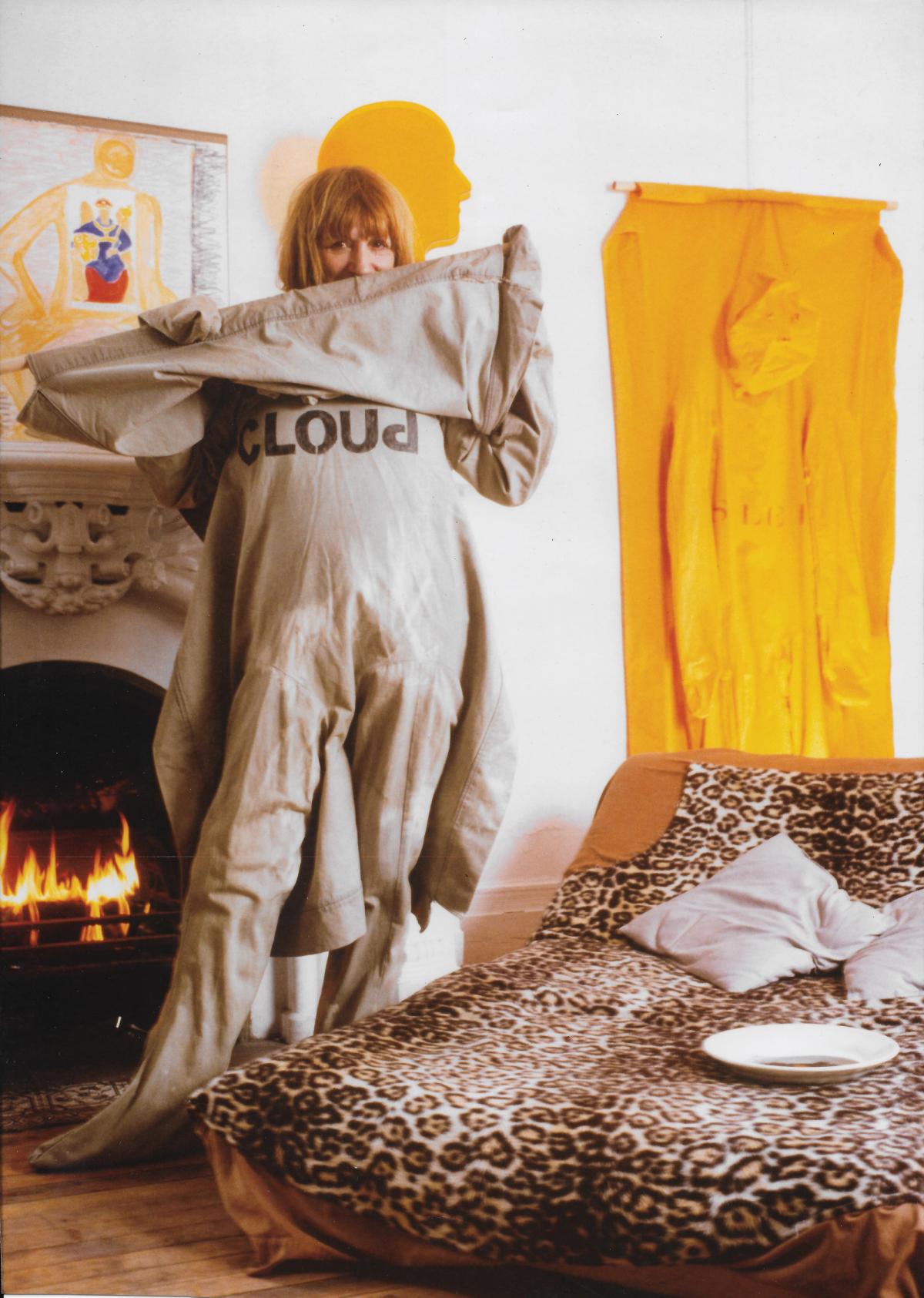

Red Coat, Same Skin for Everybody with Fernando Arrabal, New York (1992) © Nicola L. Collection and Archive.

The exhibition I Am the Last Woman Object: Nicola L., at the Camden Art Centre in London, brings together these paintings with sculpture, collage, films and performances from across six decades. Although her name is little known in the UK, the outlandish, bodily forms of works such as The Giant Foot (1967) and La Femme Commode (1969) are by now emblematic works of 1960s sculpture. For Martin Clark, the institution’s director and curator of the show, the power of Nicola L.’s work is its “refusal to be categorised” and the way that, despite the allusions to Pop art and design, it channels “a much darker reality than it might initially suggest”. Clark sees the exhibition as a rare chance to illuminate lesser-known corners of L.’s work—such as her documentary films and graphic novel—built on intimate knowledge from the artist’s family, and to reframe her practice for today’s fraught political landscape (the climate crisis and renewed anti-war activism).

Nicola L. is best known for The Red Coat Same Skin for Everyone (1969), a performative sculptural piece, made up of 11 hooded garments of shiny soft vinyl joining performers into one collective skin. It was, as Gary Indiana put it, “utopian and utilitarian”. Like the Pénétrables, The Red Coat has a considered, countercultural aesthetic and an austerity derived from Minimalist and Neo-concrete precursors, such as Lygia Pape’s Divisor (1967), a vast piece of white fabric that was pierced to allow participants’ heads to emerge. Performed in 1970, and sounding a little like a protest, The Red Coat dancers merged with a group of South American exiles, and an audience chanting: “same skin for everyone”.

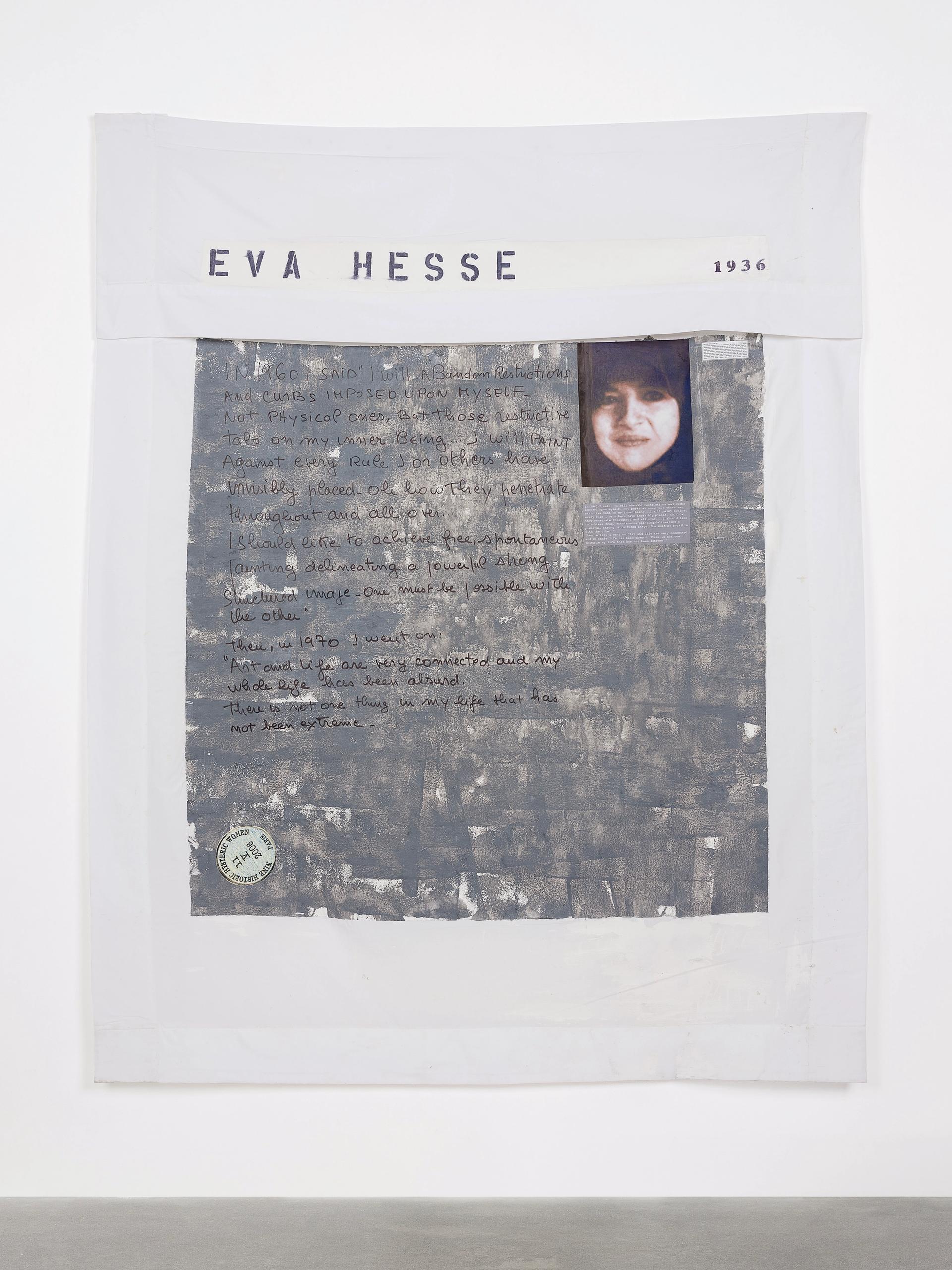

Femmes Fatales: Eva Hesse (2006) © Nicola L. Collection and Archive

Courtesy Nicola L. Collection and Archive and Alison Jacques, London; Photo: Makenzie L Goodman

Some of the allure of Nicola L.’s sculptures resides in the way new and functional materials contend with the work’s levels of reference and scale. Lips Lamp (1969), a pair of plexiglass lips floating atop a steel stand, is inspired by the time Nicola spent in Marcel Broodthaers’s fabrication workshop in 1969. It is also an eccentric shape of smooth red, the yielding, oversized plastic summoning a metaphorical image of the commodified body.

The most political of the paintings—collectively named Femme Fatales (1995) after famous women who met disastrous ends—are nine large-scale wooden boards onto which bedsheets of white cotton, swathes of ink and paint in various colours and their portraits were layered. In these dark monuments to Eva Hesse, Frida Khalo, Marilyn Monroe, L. was reclaiming female subjectivity from her male contemporaries. The artist’s attention here is fixed on something more urgent than trivial, something that transforms reality into more egalitarian and generous forms.

• I Am The Last Woman Object: Nicola L., Camden Art Centre, London, 4 October—29 December