A researcher studying multispectral images of the famous Voynich Manuscript has identified previously hidden columns of letters on its first page. The three columns—two bearing letters of the alphabet and one of unreadable “Voynichese” characters—appear to have been added by one of the manuscript’s early owners to decrypt its mysterious writing.

“I may have shrieked when I saw the marginal alphabets,” says Lisa Fagin Davis, the executive director of the Medieval Academy of America, who studied the lost writing and published her findings on her blog, Manuscript Road Trip. “And it is always exciting to be able to identify a mystery script with a particular person, especially, in this case, someone with a known connection to the manuscript.”

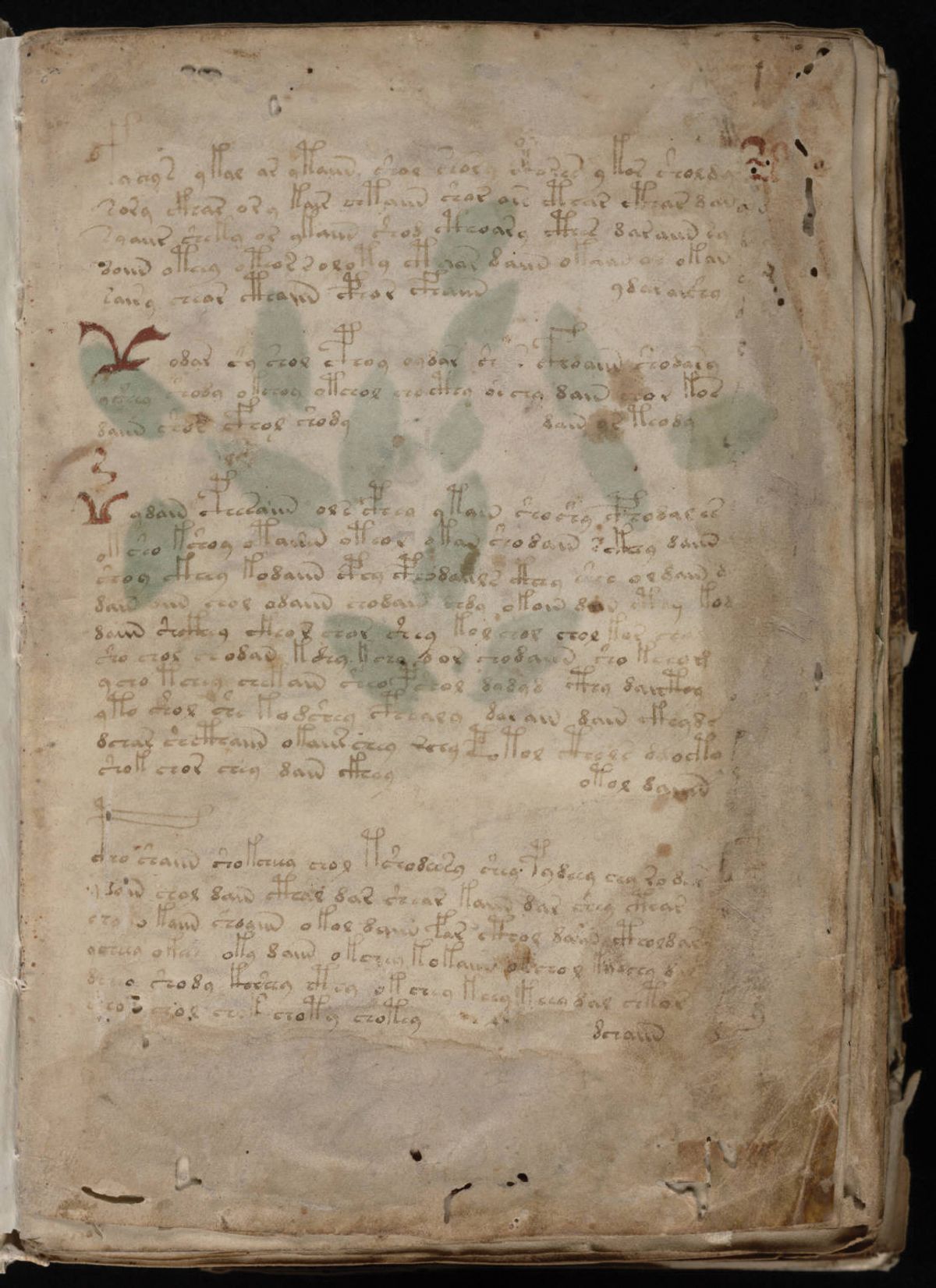

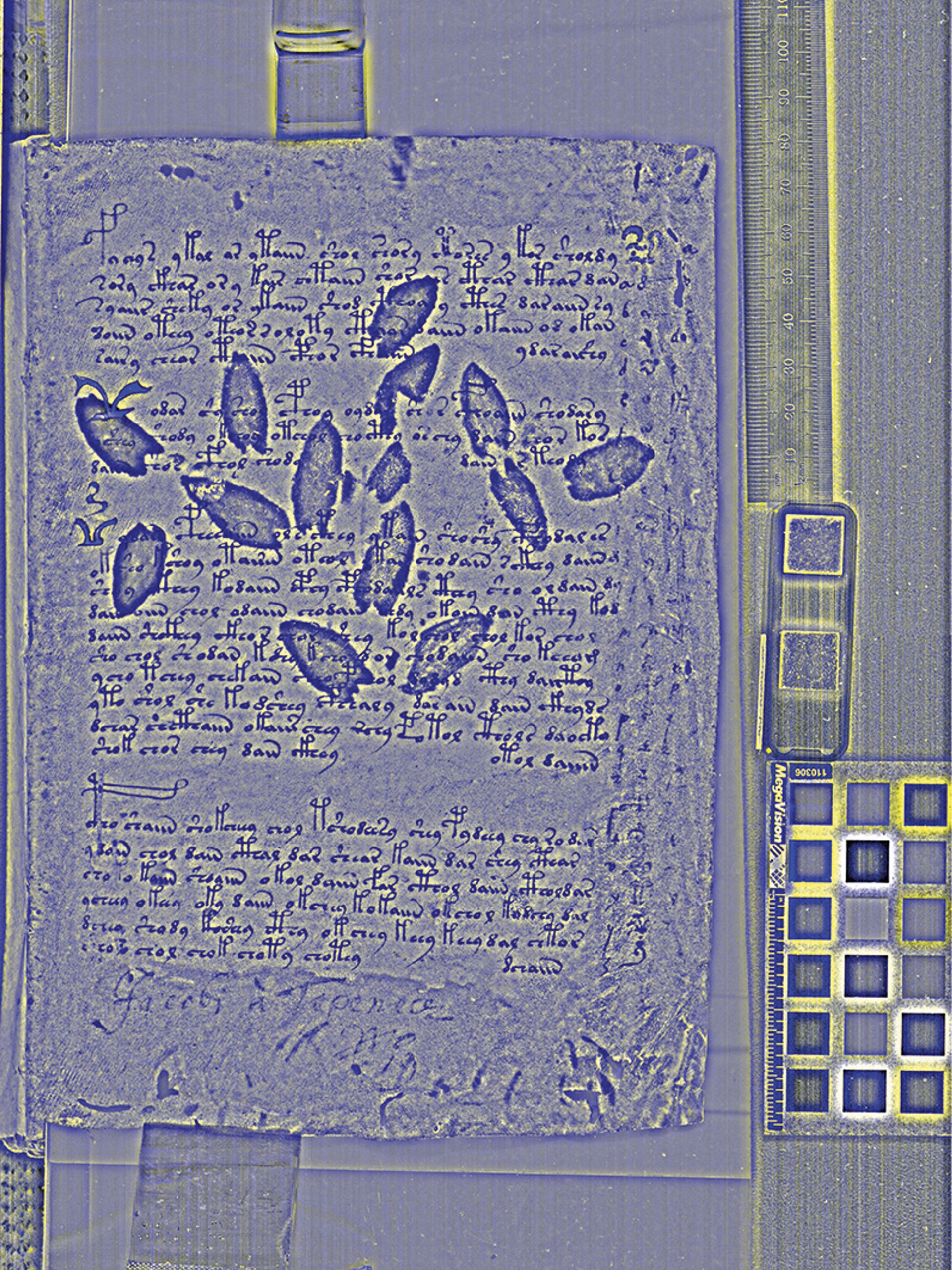

Multispectral imaging of the Voynich Manuscript’s first page reveals three columns of letters in the right-hand margin, believed to have been added by Johannes Marcus Marci, the manuscript’s owner in the 1660s The Lazarus Project and The Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science at Rochester Institute of Technology

Cipher or hoax?

Filled with unreadable words in an invented script, and dubbed the world’s most mysterious manuscript, the early 15th-century Voynich Manuscript has long puzzled researchers. Some experts regard its unusual symbols as a cipher, code or artificial language and script, while others believe it to be a late Medieval hoax. “The biggest problem is that we are unable to read it,” Davis says. “Linguists and cryptologists continue to apply sophisticated analytics to the text in order to discern underlying patterns, but to no avail so far. The more data we have, as revealed by these scans, the more the work can move forward.”

Davis identified the lost letters thanks to a technique called multispectral imaging, which can reveal faded writing and even erased text. The Lazarus Project, a multispectral imaging collaboration based at the University of Rochester, New York, took the multispectral images of ten Voynich Manuscript pages in 2014, and recently gave Davis permission to make them public. It was on the manuscript’s first page that she spotted the lost letters hiding in the right-hand margin: two columns of Roman letters and one of Voynich characters.

It is always exciting to be able to identify a mystery script with a particular personLisa Fagin Davis, researcher

Once Davis had identified the previously hidden letters, she studied their handwriting and compared it to that of people known or believed to have interacted with the Voynich Manuscript over the centuries. She found that its characteristics best matched the hand of Johannes Marcus Marci, a Prague doctor, who owned the manuscript from 1662 to 1665. “Because some of the Roman-alphabet lettering in the margin of the first page was already visible, I expected that processing of the multispectral images would reveal the rest of the alphabet,” Davis says. “What was entirely unexpected was that there were three columns of lettering and that these would provide enough evidence for me to be able to identify the handwriting as Marci’s.”

From Prague to Rome

Although Marci’s reason for writing these columns of letters is not known, Davis suggests that he may have been attempting to decrypt the text using two different substitution ciphers, or that he was developing his own cipher using Voynich characters. Whatever the case may be, in 1665, Marci sent the manuscript to Athanasius Kircher in Rome, believing that the renowned Jesuit scholar had a better chance of revealing its secrets. It was rediscovered in 1912 by the rare books dealer Wilfrid Voynich, and is now kept in Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library in New Haven, Connecticut.

“Marci only owned the manuscript for three years, and we have never known what he made of it, other than the evidence in the letter he sent to Kircher when he gave him the manuscript in 1665,” Davis says. “Knowing that he made some effort to decrypt the manuscript adds to our understanding not only of his interest in the Voynich Manuscript but of Marci as an intellectual figure in mid-17th-century Prague.”

The multispectral images may now lead to further revelations. “Some of the scans reveal faded text,” Davis says, “suggesting that there is more to discover.”