Queen Sonja of Norway has described art as a “unifying force” at a time when politics has become particularly polarised, not only in Europe but across the globe. Right wing and far-right parties are expected to gain ground in the European elections this week, though Norway is not a part of the EU so Norwegians will not be voting.

Speaking at the Queen Sonja Print Award (QPSA) ceremony in Bodø, northern Norway on Wednesday evening, the queen highlighted the importance of open communication and culture in “turbulent times”. She added: “We just have to go on.” Bodø is one of three European Capitals of Culture in 2024, with at least 1,000 events scheduled for throughout the year.

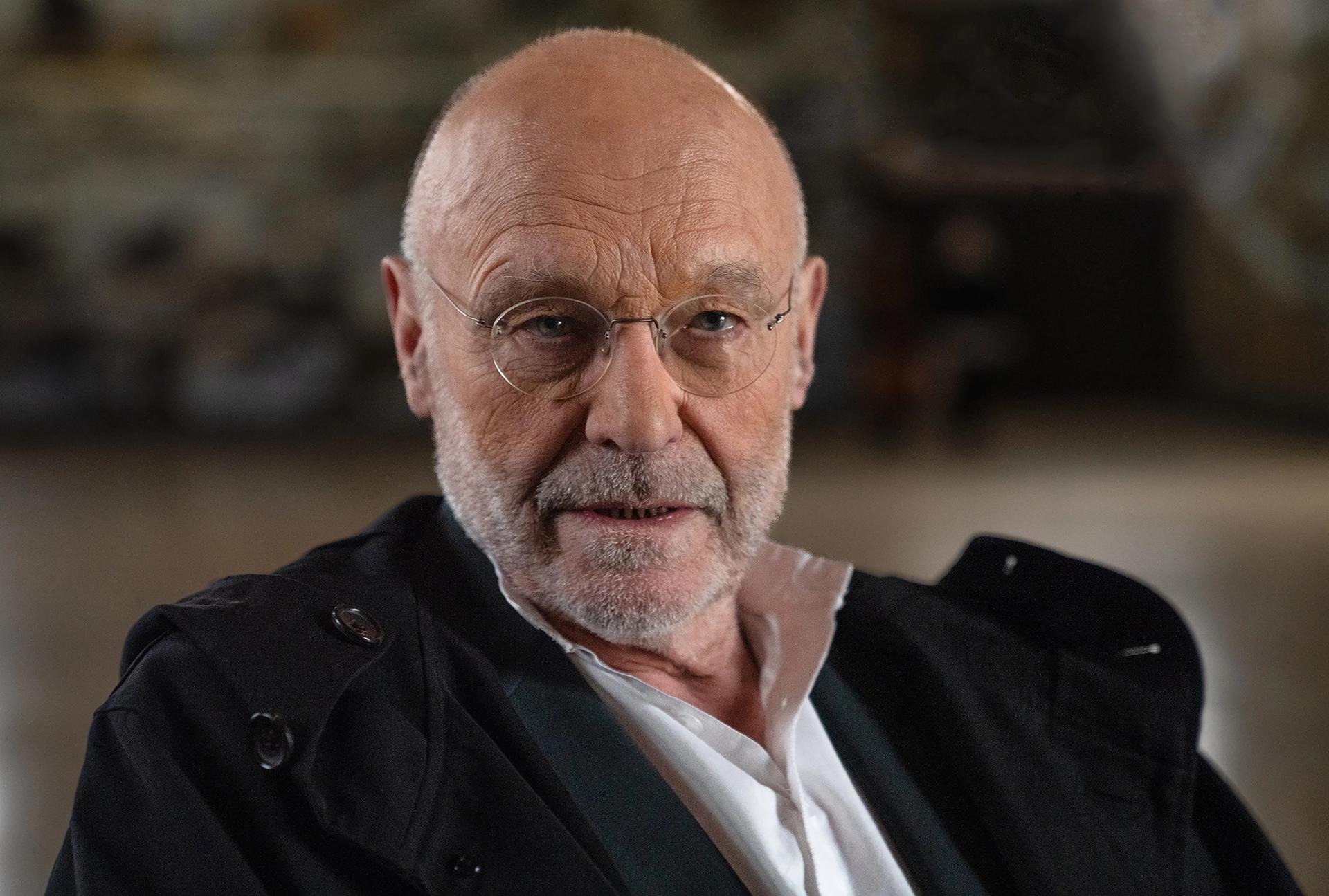

The historian and television presenter Simon Schama, who gave a talk on the history of printmaking and the work of Anselm Kiefer, thanked Queen Sonja, not only for her “extraordinary work promoting the importance of graphic art”, but for also being “a guardian angel for the integrity of culture” now that the “threatening age of AI is upon us”.

Kiefer was awarded the Queen Sonja Print Award Lifetime Achievement Award, while the Sámi artist Tomas Colbengtson won the Queen Sonja Print Award 2024 and the Swedish artist Maria Kayo Mpoyi won the QSPA Inspirational Award. Queen Sonja said she was “delighted” that this year’s prestigious award had gone to a Sámi artist. “Tomas Colbengtson’s work is already represented in museum collections and I hope this prize will make his work known even more widely internationally,” she said.

Sámi artist Tomas Colbengtson is the recepient of The Queen Sonja Print Award for 2024 Photo by Elisabeth Ohlson

Cultural destruction

Colbengtson spoke of his anger at how Sámi culture was all but destroyed in Norway in the first half of the 20th century. Today there is a renewed focus on Sámi culture and art, though Indigenous communities are still facing the loss of their livelihoods and identities, due to a failure to respect their rights. In Norway, attempts to transition from oil and gas to wind power have meant that areas of land traditionally used by Sámi people to graze reindeer have been taken over for turbines.

One of the measures of great art is that it’s likely to give you insomniaSimon Schama, historian

Conflict rather than peace was at the heart of Schama’s talk on printmaking. The historian reluctantly took issue with the Norwegian playwright and Nobel Prize winner Jon Fosse, who said in March that “War and art are opposites, just as war and peace are opposites—it’s as simple as that. Art is peace.”

Schama countered: “It would be nice to think that art was the conveyor of peace. But I’m frankly not sure about this. I don’t know that anyone who has an encounter with the Sistine Chapel comes out feeling more peaceful, or with a Caravaggio, or with Jackson Pollock, or with one of the great works of Anselm Kiefer. I think art has the capacity, like strong history, to be a disturber of the peace. One of the measures of great art and great history, I think, is that it’s likely to give you insomnia, even if there is no midnight sun around.”

German artist Anselm Kiefer was awarded The Queen Sonja Print Award Lifetime Achievement Award Photo by Summer Taylor

Thuggish masterpieces

Schama went on to say that great art has “dreadful manners”. He added: “The hushed reverence of the gallery can fool you into believing that masterpieces are polite things, visions that soothe, charm and beguile, but actually, they are thugs. Merciless and wily, the greatest works grab you in a headlock, rough up your composure, and then proceed in short order to rearrange your sense of reality.”

For decades, Schama has written about Kiefer’s work, which encompasses printing, painting and sculpture on a relentlessly large scale. Rooted in his experience growing up in the aftermath of Nazi Germany, Kiefer has continuously wrestled with the dark underbelly of humanity in his work. As Schama puts it, Kiefer is a “peerless master” on the relationship between “nature, pain and memory”. And it is perhaps through a confrontation with pain, tragedy and cruelty, Schama suggests, that a great work of art might possibly bring you some sense of peace.