The future of Ontario Place, a historic Modernist landscape just off the Toronto waterfront, hangs in the balance as local politicians and area residents argue over how to revitalise the artificial islands that together serve as its site. The squabble came to a head in December, when Ontario’s provincial government passed the Rebuilding Ontario Place Act, overriding its protections as a heritage site and exempting it from environmental assessment.

Many see the move as effectively pushing through a controversial plan to construct a mega-spa and waterpark at Ontario Place—a project that detractors say would not only build over the late Canadian landscape architect Michael Hough’s design but also largely privatise a much-loved public space. Days after the new law was introduced, Ontario’s Ministry of Infrastructure began cutting down trees at the site.

Ontario Place is deeply rooted in and an exemplar of Modernism. What’s proposed now obliterates the landscape as we know itCharles Birnbaum, Cultural Landscape Foundation

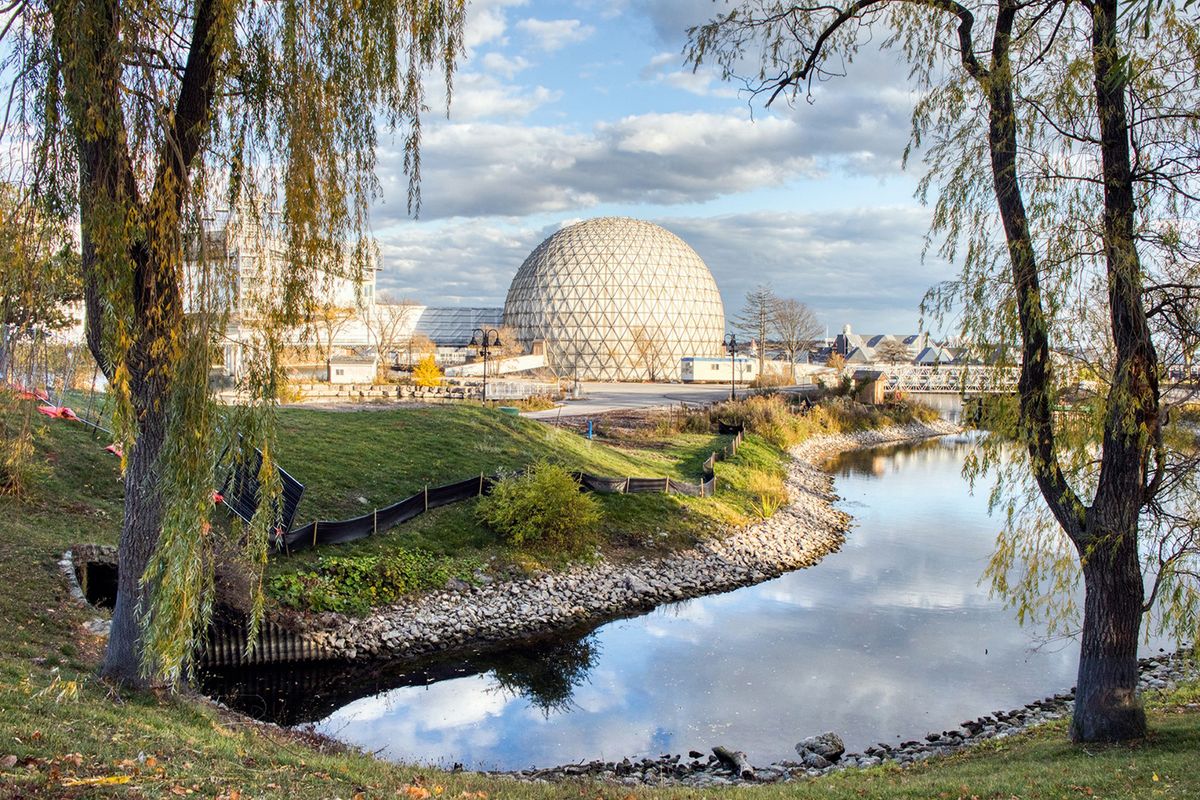

“Hough is the most significant post-war landscape architect in Toronto, and Ontario Place is a seminal work by the master,” Charles Birnbaum, the founder of the Cultural Landscape Foundation, tells The Art Newspaper. “Ontario Place is deeply rooted in and an exemplar of Modernism—both the buildings and the tree canopy created to cradle them. What’s proposed now obliterates the landscape as we know it.” (Ontario Place’s Cinesphere, the world’s first permanent Imax theatre, designed by the architect Eberhard Zeidler, is not affected by redevelopment plans. Nor are Zeidler’s historic “pods”, pavilions suspended above the water.)

Inspired by the success of the built landscapes of Montreal’s 1967 World’s Fair, Ontario Place first opened in 1971 as a unique amalgamation of public and private space in what, at the time, was a popular “futuristic” aesthetic. Over the years, various projects have opened and closed—including Children’s Village (designed by the “father of soft play” Eric McMillan, who invented the ball pit), an open-air theatre, a theme park and a water park—among its landscape of native flora. Although parts of the islands fell variously into states of disrepair over time (and the area was closed between 2012 and 2017), Ontario Place was recognised as a heritage site by the province in 2014 and by the city of Toronto in 2019.

Election issue

This redevelopment feud has been ongoing since 2018, when then newly elected Ontario premier Doug Ford—leader of the centre-right Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario and a brother of the late Toronto mayor Rob Ford—announced a call for development proposals for Ontario Place without any input from the public or protections for the heritage site.

As a result, Ontario Place was added to the World Monuments Fund’s 2020 watch list of sites “in need of urgent action”. When information came to light in 2022 of plans to build a C$350m ($260m) spa on the site’s West Island, for which taxpayers would pay C$450m ($334m) for a parking garage and C$200m ($147m) towards site servicing, Ontario Place became a key issue in Toronto’s mayoral election. (The Austrian wellness company Therme will cover the C$350m construction cost.)

Many people have credited Olivia Chow’s election win this past summer to her opposition to the project—but in a November deal, the new mayor (a member of the centre-left New Democratic Party) agreed to back down in exchange for C$1.2bn ($892m) from the province towards much-needed infrastructure improvements and housing in the city.

The lengths that Ford’s government is willing to go to in order to appease Therme’s spa proposal, including a 95-year lease and more than C$2m ($1.5m) in taxpayer money to “raise awareness” of the redevelopment plan, have shocked Toronto residents, leading some to question provincial politicians’ motives. Norm Di Pasquale, a co-chair of Ontario Place for All—a grassroots organisation that is suing the provincial government over its redevelopment plans—calls the whole situation “nefarious”, particularly given that the Ford government has kept its contracts and dealings a secret. (The provincial government has refused to make the contract terms public, and The Art Newspaper’s questions to numerous provincial officials remain unanswered.)

The province investing in private development and parking is a bad use of public fundsAusma Malik, deputy mayor of Toronto

Ausma Malik, the deputy mayor of Toronto (an independent affiliated with the New Democratic Party), has been particularly vocal in her opposition to the current plan. “The province investing in private development and parking is a bad use of public funds,” she says, calling Ontario Place an “incredible heritage landscape, a gem in the city” that has especially gained popularity since the Covid-19 lockdowns of 2020. She is particularly worried about the province’s “non-democratic approach” to this project, its dismissal of the concerns of Toronto’s city government and its citizens, and its overall lack of transparency. “Extraordinary powers were used to push this forward,” she says, “and it sets a dangerous precedent for the government to ignore its obligations.”

Updated rendering

On the design side of things, Gary McCluskie of the architecture firm Diamond Schmitt, charged with designing the much debated Therme Canada building, says that plans for the spa changed drastically “in response to community feedback last April”. He notes that an updated rendering from August 2023 includes a giant public park on the roof of the spa building, which itself has a lower height than originally planned so as not to block the view from the shore. McCluskie adds that the plan is “redesigning and reinforcing the original Hough design” with “incredible respect for the Hough approach”, including the use of native plants.

“The whole thing is so ludicrous,” says Walter Kehm, a landscape architect who worked on Ontario Place’s current redevelopment before demonstratively quitting not only the project but his own firm (LANDinc, which is still contracted to do the work) in November in protest of tree clearing. Kehm, a friend of Hough’s, says that his concerns about how cutting down the tree canopy would negatively affect the wildlife habitat were ignored. He calls Ontario Place’s original design “an ensemble of building and landscape, like a painting” and the current redevelopment plans “like slashing a Michelangelo. So I had to quit.”

Kehm’s intimate familiarity with Ontario Place includes his work as lead designer on Trillium Park, a public landscape completed in 2017 on the site’s East Island. “We selected and planted every tree and rock there,” Kehm says. Trillium Park is often held up as the gold standard for the whole of Ontario Place; Di Pasquale calls it “an amazing new park and an example of what the rest could be”, and Malik deems the space “incredible, well-used and well-loved—at the fraction of the price” of the spa project.

So, what happens now? Two court cases are waiting to be heard, which could block construction of Therme Canada (at least temporarily), and a much anticipated report from Ontario’s auditor general on the project is expected later this year. A previous auditor-general investigation found some irregularities in the provincial government’s related plan to move the Ontario Science Centre to Ontario Place—a project that has also caught flack, in part because the proposed new space would be notably smaller than its current landmark building, designed by the architect Raymond Moriyama, which has fallen into disrepair. (“Not every amenity needs to be right downtown,” Di Pasquale says. “And teachers have said downtown is not a good place for the science centre.”)

There is also a widespread fear that Ontario Place is just the latest in a troubling trend of governments valuing private enterprise over public space. “What’s happening in Canada echoes what’s happening in the US,” Birnbaum says. “It’s a moment of what starts to feel like urban renewal 2.0—we’re being told by the bureaucrats that they know what’s best (there’s a certain arrogance to that), and there’s a pattern of privatisation of public open space.”

“Wellness is trees, forests, parkland and where we can breathe and just be,” Di Pasquale says, noting the irony of the spa project. “You wouldn’t do this in Central Park.”