One of the London art market’s best-known faces is trying something slightly different, launching a business that will sell primary market works by a mixture of emerging artists—some fresh out of art school—as well as more established names.

Not strictly a gallery, the new venture by Matt Carey-Williams (formerly of Victoria Miro and Phillips auction house, among others) will have a physical space on Porchester Place just north of Hyde Park as well as a nomadic component.

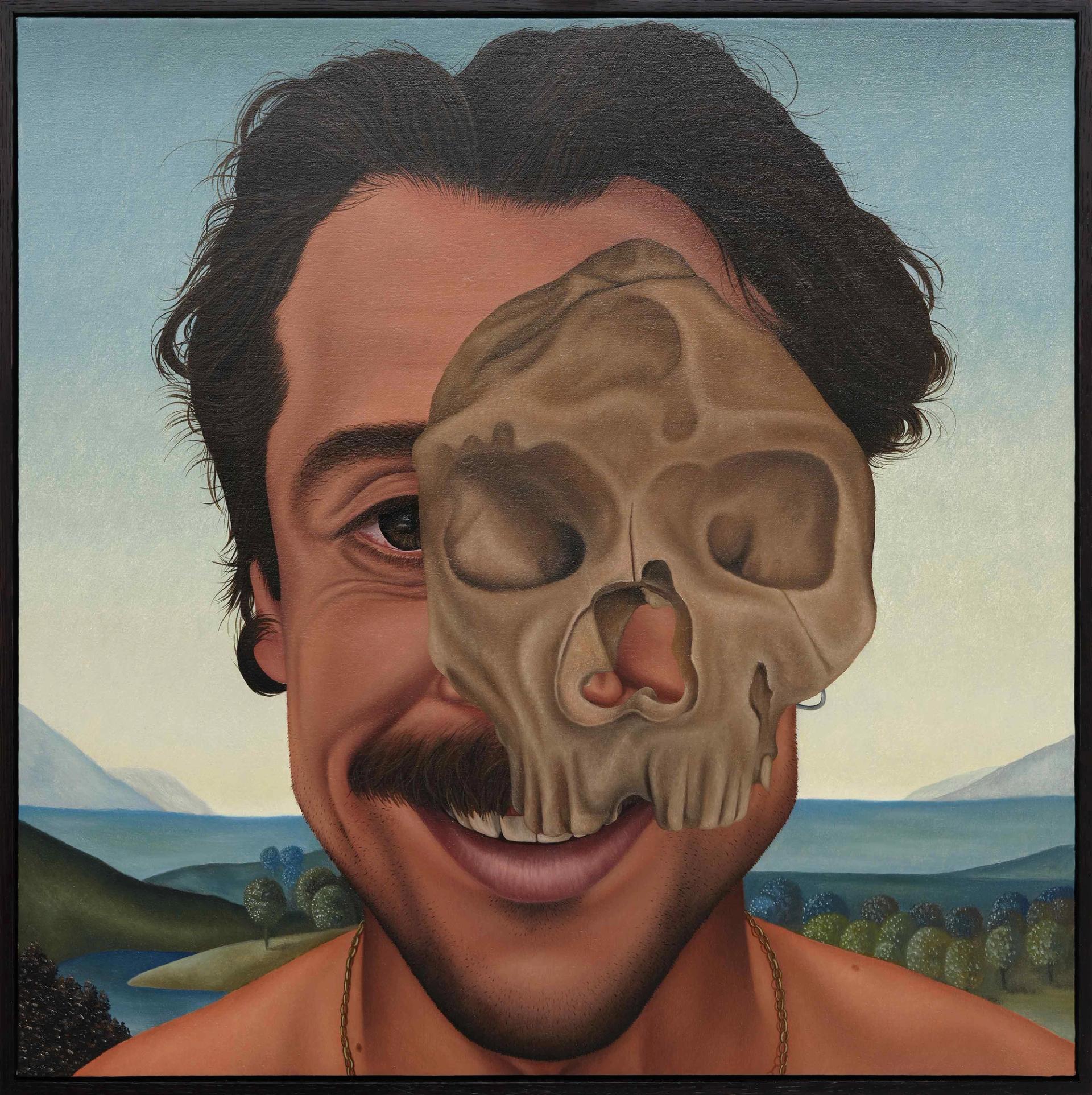

The first exhibition at Porchester Place, which presents single bodies of work as a series of “scenes”, focuses on the work of London-based artist Glen Pudvine, whom Carey-Williams met while he was still at London’s Royal Academy Schools. The show’s title, Mug, is a reference to both the drinking vessel and the slang for a face. Carey-Williams adds that the fact the word is also slang for “fool” makes it even more fitting: “With so many ‘mugs’ both running and ruining our world, I could not have hoped for a more telling start to my programme.” The presentation runs from 6 February to 2 March, with prices ranging from £3,500 to £11,000.

Glen Pudvine's Glen and Gibraltar 1 in Perugino (2023) will be included in Carey-Williams's first show on Porchester Place

The first nomadic exhibition, titled Bump, opens in March at No. 9 Cork Street (the gallery space run by Frieze Art Fair) with a show of work by 21 artists including Marius Bercea, Rachel Howard, Jessie Makinson, Jin Meyerson, James White, Clare Woods and Flora Yukhnovich. Future editions are planned to take place in Seoul this autumn and Rome at a later date.

Carey-Williams acknowledges that he is acting much as any private dealer or auction house executive might in showing and selling art, but says he is trying to “bring all the protagonists around the table in a slightly different way”. For instance, he has no plans to represent artists in the traditional sense. “I’ll work directly with artists if they don’t have a gallery, or in collaboration with their galleries if they do have representation,” he says. He will quickly be collaborating with his former employer Victoria Miro, which represents Yukhnovich.

Speaking of some of the younger artists he is working with, Carey-Williams says: “A lot of these guys are not interested in representation right now, they want to take their time, they want to look around. I’m giving them an opportunity to put their head above the parapet and breathe in the air and see if people like what they’re doing or not.” Crucially, it is not about “giving 25-year-old starlets 15 minutes of fame”, he adds. “It’s really about creating a textured programme.”

The art market’s contraction has by now been well-documented—and different ways of doing business are emerging out of that. Carey-Williams observes a “slowing down” of the “old order”. As he puts it: “What I mean by the ‘old order’ is this gallop to get from small space to giant gallery as quickly as possible—that’s changed. We’re not in this strange late 1980s-90s thirst to outdo everybody else. There’s a generosity of spirit that I have already experienced with this project—people want to work together.”

Of the art market at large, Carey-Williams says he is “not overly concerned” about the “mechanics of the economy”. Where the trade really works, he suggests, “is where people join up the dots and make connections”.