Even if you have somehow never heard of Elliott Erwitt, the great French American photographer who died on 29 November at the age of 95, you will instantly recognise many of his pictures.

“He was unquestionably a great photographer,” says photographer Martin Parr, a colleague at Magnum Photos, the artist-owned agency of which both were members. “I can think of at least 10 of his images that are etched into my consciousness.”

There is his picture of Richard Nixon prodding a finger into the chest of the Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev during an impromptu discussion during the height of the Cold War in Moscow in 1959. Or his photograph of a grief-stricken Jacqueline Kennedy at her husband's funeral, four years later. There are his iconic portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Che Guevara, Grace Kelly, Arnold Schwarzenegger and countless others.

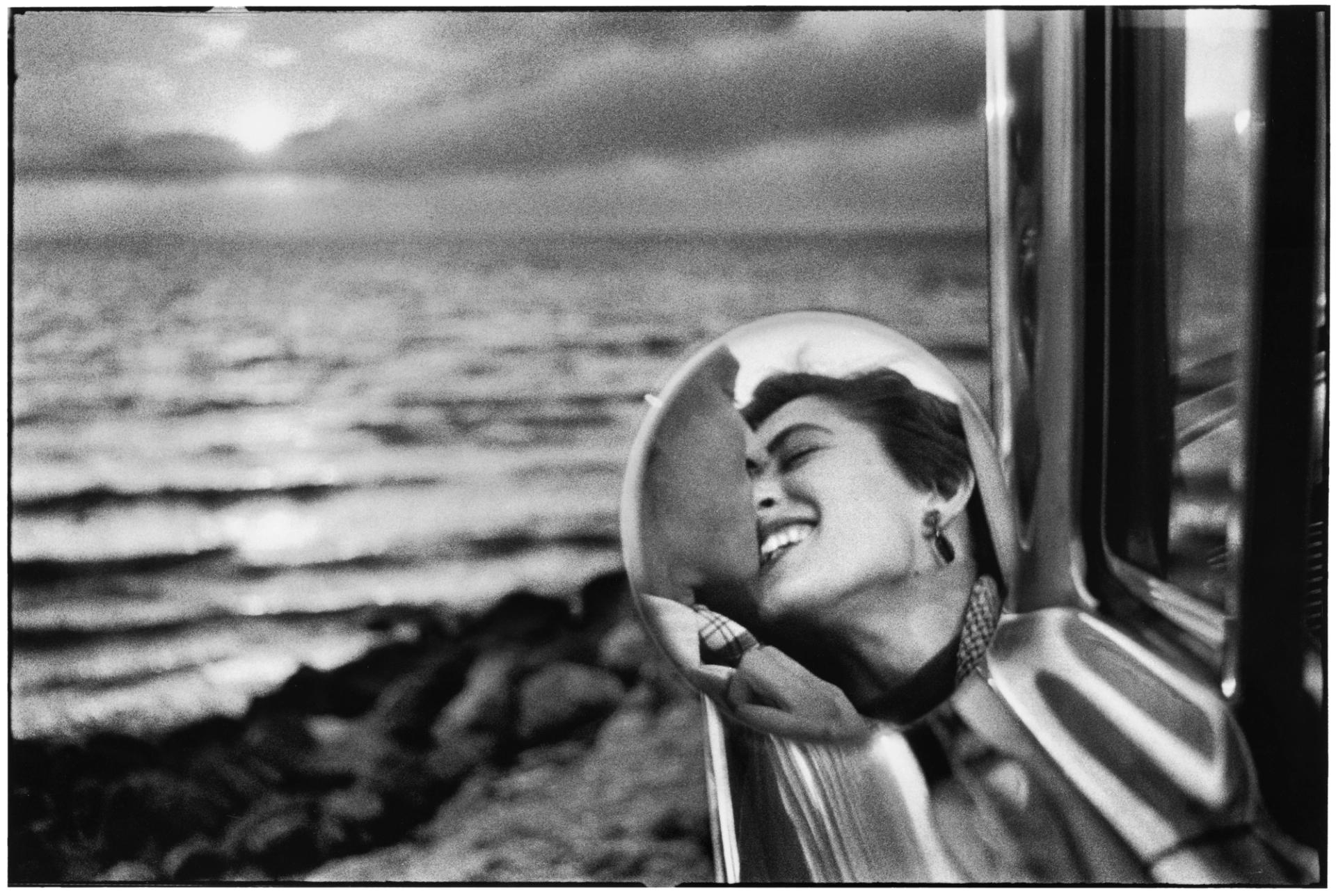

USA. California. Berkeley. 1956 © Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos

But it is his photographs of everyday life for which he is best remembered, be it his picture of a couple caught leaning in for a kiss, captured in a car wing mirror set against a California seascape, or his comical ground-level shot of a woman’s shiny leather boots, flanked by a Great Dane and a Chihuahua.

"It's about reacting to what you see, hopefully without preconception,” Erwitt once said. “You can find pictures anywhere. It's simply a matter of noticing things and organising them. You just have to care about what's around you and have a concern with humanity and the human comedy."

He was born in Paris in 1928, the son of a Russian Jewish father and Russian mother who had emigrated to France following the 1917 Revolution. Originally named Elio Romano Ervitz, he spent much of his early childhood in Italy, moving to the US with his parents, who by then had separated, just before the outbreak of the Second World War. It was in Los Angeles in the mid-1940s that the teenage Erwitt began taking photographs seriously, hustling for work while employed at a commercial darkroom and studying at a local college.

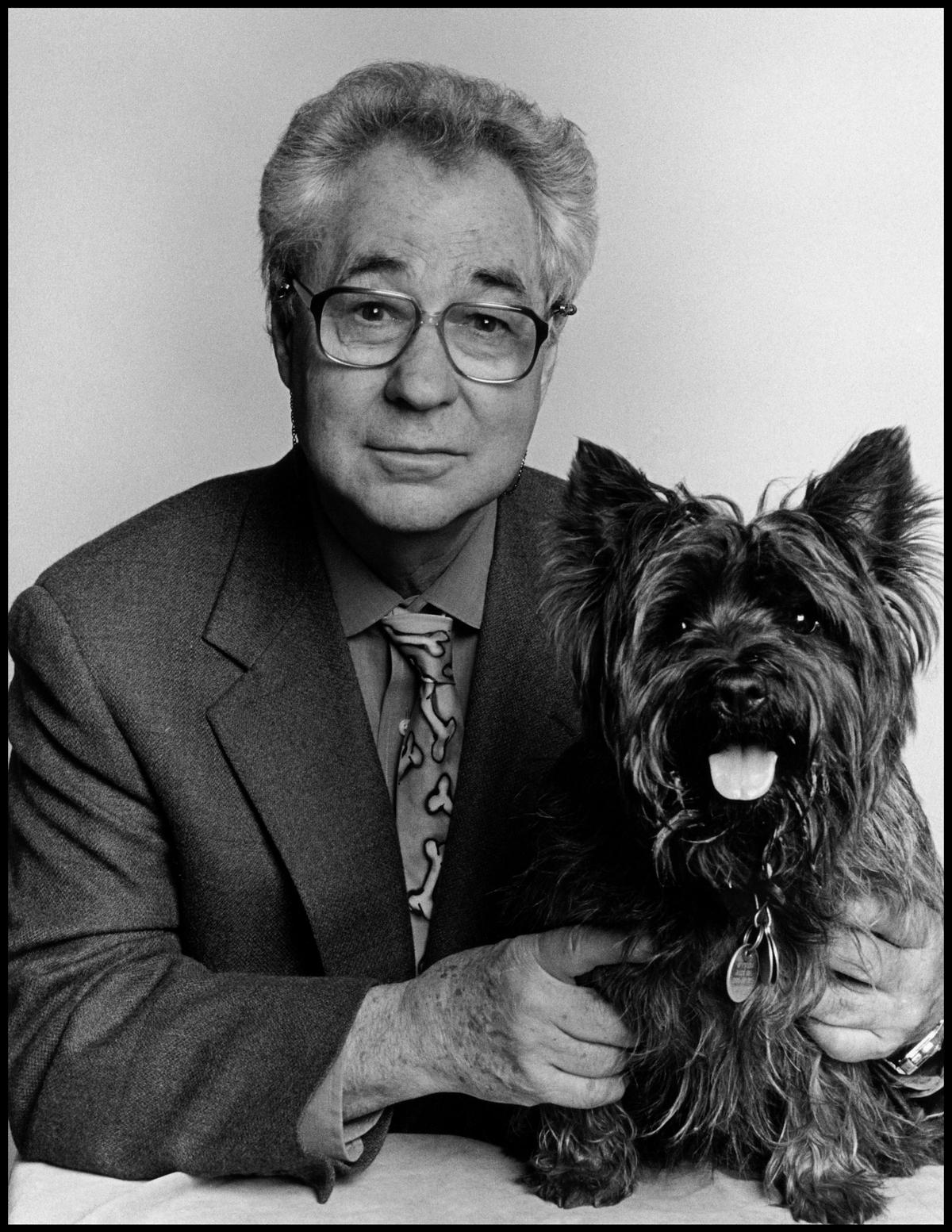

USA. New York, New York. 1974 © Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos

He moved to New York in 1948 and began his fledgling career as a photographer. Crucially, he also got to know influential figures such as Edward Steichen, who had just been appointed director of the department of photography at New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and Robert Capa, who had recently co-founded Magnum Photos. Erwitt also met Roy Stryker, the former head of the Farm Security Administration, who had played an important hand in the careers of Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Gordon Parks and others, and who began commissioning him, including an assignment for a series on Pittsburgh in 1950, published as a book some 67 years later.

Erwitt was drafted to the US Army in 1951, during the Korean War, but continued shooting pictures while off duty. One such photograph, shot at a barracks in France, which he titled Bed and Boredom, kickstarted his career when he entered—and won—a Life magazine contest. Back in New York at the end of service, he set out on a prolific freelance career, joining Magnum in 1953 and shooting assignments for the likes of Life and Holiday during the golden era of illustrated magazines. Alongside his commercial photography practice, he was always making his own observations of everyday life.

Over the next two decades, he was prolific, a committed freelancer who shot major commercial assignments alongside editorial commissions, and who also always carried a camera with him, finding witty and poignant observations in the ordinary.

From the mid-1960s, major institutions in the US began to recognise his work, MoMA being the first to give him a solo show (The Impossible Image, 1964), followed by the Art Institute of Chicago, the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane and Kunsthaus Zürich. Since the mid-1990s, there has been an almost constant flow of Erwitt exhibitions. Earlier this year, a retrospective at the Musée Maillol in Paris was visited by more than 150,000 people, according to Andrea Holzherr, the global cultural director at Magnum.

USA. Wyoming. 1954 © Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos

In the 1970s, collectors began taking serious interest in his work, and the first of more than 30 books of his images was published. He also branched out into making documentaries. “I liked the way he navigated between the commercial and artistic,” says Parr. “He also never editioned prints, arguing that there was no reason to do this. If he sold prints, which he did in huge quantities, it was on his terms, not those of the market.”

And yet there is still a feeling that Erwitt has not been given the attention he deserves. “Although a comedian, he was also a very serious photographer, but he disguised this with his wit and charm,” says Parr. And this is why he remains somewhat overlooked, says Stuart Smith, the acclaimed designer and co-founder of GOST Books, who published Erwitt’s last title, Found Not Lost, in 2021. “In time he’ll be recognised, because the kind of photography that he did—shooting from the hip—is the hardest thing to do. But because he used humour, he wasn’t taken as seriously as some of his contemporaries, such as Robert Frank.”

For many in the photography world, he is one of the post-war greats. He elevated the snapshot to an artform, creating images that appeal directly to the emotions, pictures that immediately resonate with a wide public. And, judging by the crowds queuing for his retrospective at the Maillol, the appeal is timeless.

“What the public loves about his work is this very particular way of photographing,” says Holzherr. “He’s like the Charlie Caplin of street photography; he had this gift for making pictures that can be funny or sad at the same time.”