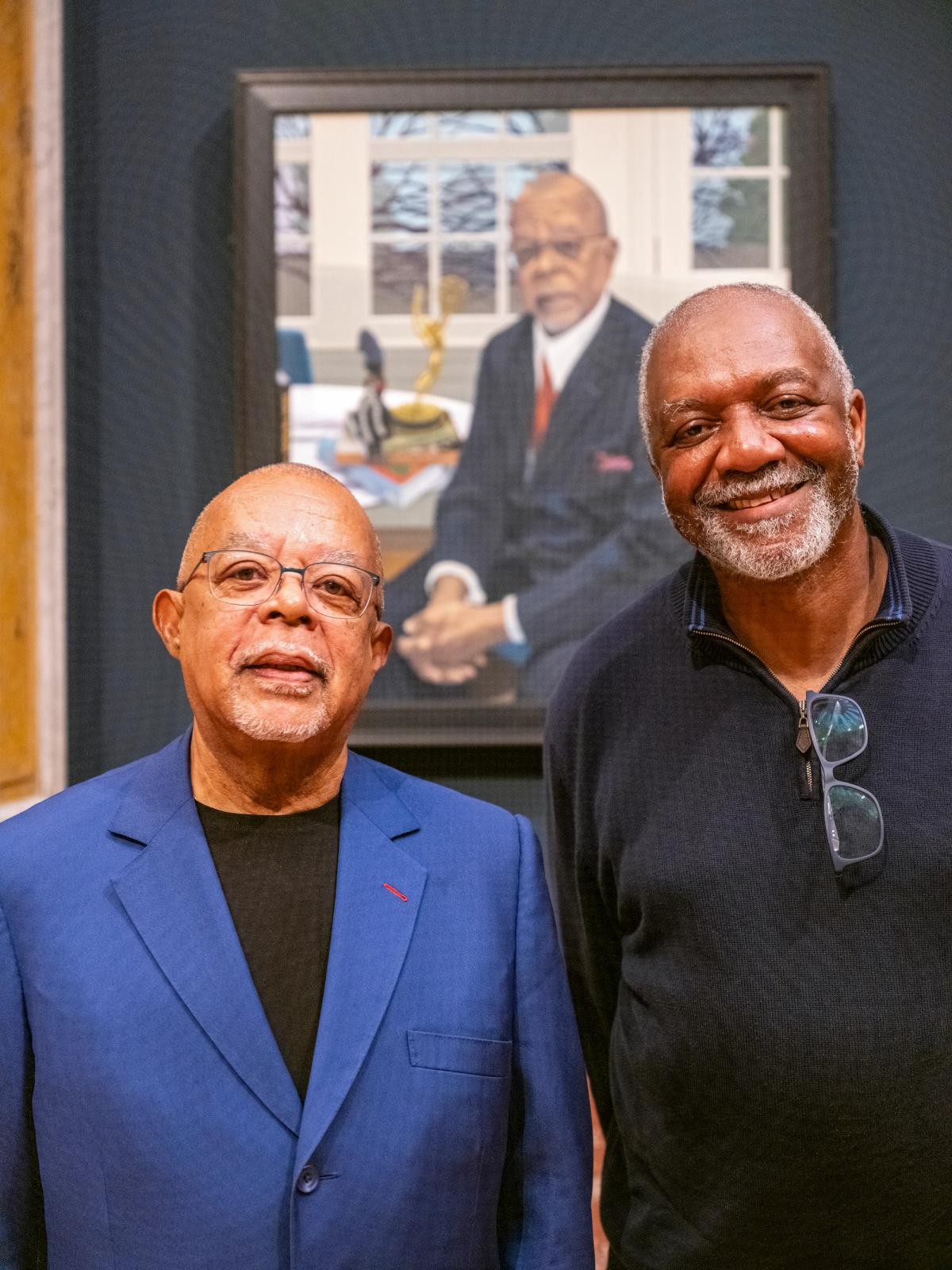

The acclaimed American artist Kerry James Marshall has donated a portrait of the Harvard academic Henry Louis "Skip" Gates Jr. to the University of Cambridge.

The work is Marshall’s first ever formal portrait of a living sitter, and is only the second work by the artist—widely regarded as one of the greatest figurative painters working today—to join the collection of a public institution in the UK. It will hang at the university's Fitzwilliam museum.

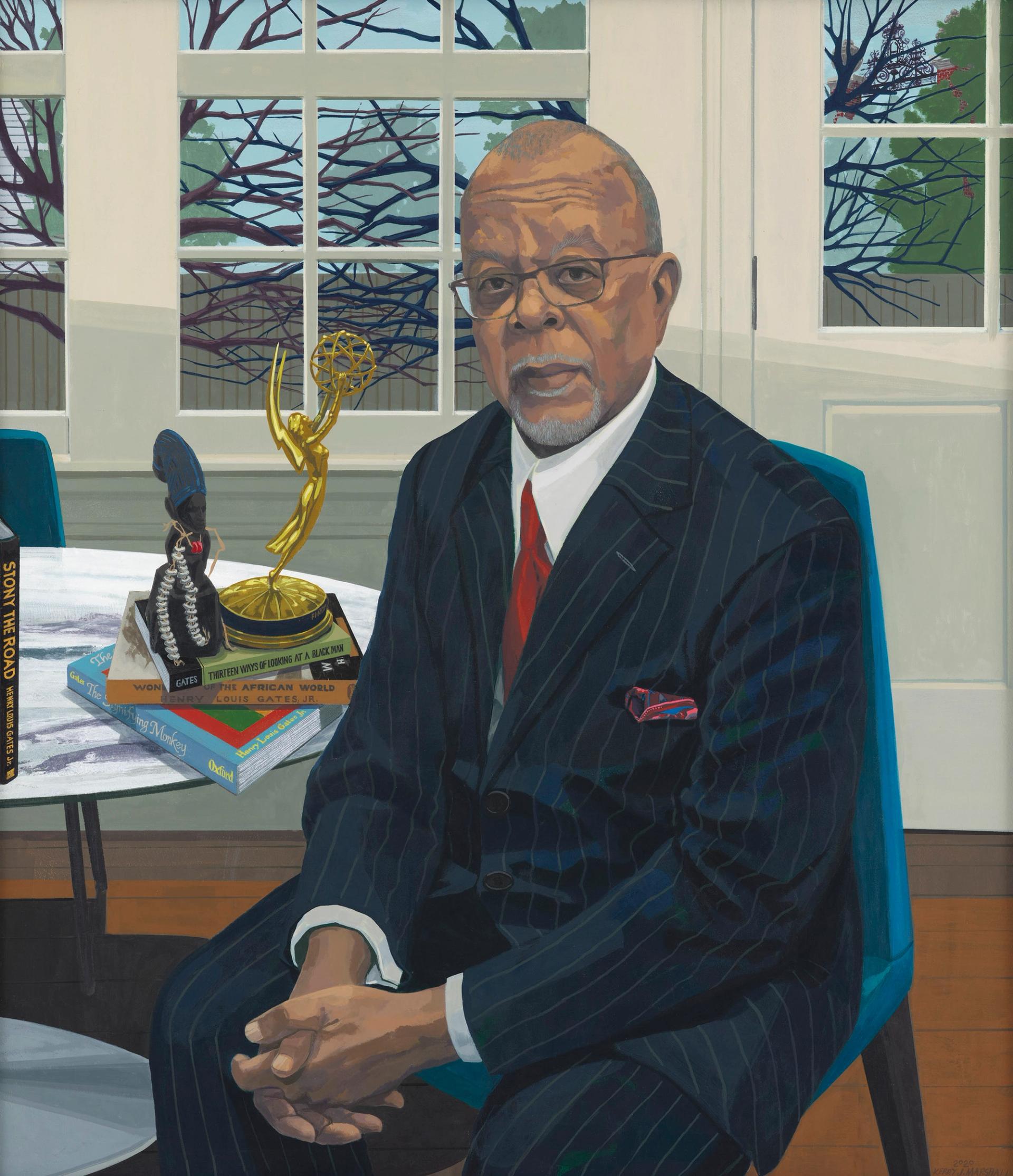

Gates is a notable alma mater of Cambridge University. In 1973, aged 22, he became the first African American person to be awarded a Paul Mellon Fellowship to study at the Cambridge's Clare College. He was one of only three Black students at the college at the time.

He is now the director of the Hutchins Center for African and African-American Research at Harvard University, where he is known for rediscovering some of the earliest known African-American novels. During the unveiling of the portrait at the Fitzwilliam on Monday 2 October, Marshall described Gates as the “W. E. B. Du Bois of our generation”, in reference to the leading activist, sociologist and historian who died in 1963.

Gates, in return, said Marshall was “a living genius” whose paintings “have redefined our understanding of Blackness as being multiplicitous.”

“What I render historically, he renders visually,” Gates said of Marshall.

Kerry James Marshall, Henry Louis Gates Jr., 2020 © Kerry James Marshall, courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, London

During the unveiling, Marshall was asked to reflect on how racial justice in the US had changed in his lifetime. Marshall was born in Alabama, in America's Deep South, 13 years before the US civil rights movement resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

“Of course, we’ve seen a lot,” he said. “I was born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955. Now that’s supposed to mean something, but I don’t think it means what a lot of people want it to mean. Our lives were not overwhelmed by misery. That’s not how we lived.”

Marshall moved with his family to Los Angeles as a child, and, in high school, began figure drawing under the mentorship of social realist artist Charles White before later studying at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, where he was later awarded an honorary doctorate in 1999.

“I’ve spent most to my life in south-central Los Angeles,” he said. “I saw the Watts riots in 1965 up close. I saw the Black student union protests in 1968 up close. I remember the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Robert Kennedy. All of that was going on. It was all the same kind of chaos that’s going on now.”

In 2013, he was one of seven new appointees to President Barack Obama’s committee on the arts and the humanities. Last month, two stained glass windows, created by Marshall, were unveiled at Washington National Cathedral in Washington, DC. They were created to replace images of two generals from the US Confederate army.

“I am not a utopian in my thinking,” Marshall said. “I'm not looking forward to something that’s supposed to be better than what’s happening right now. I’m interesting in looking at things that are in the moment, immediately, right now, and I’m interested only in things that I can do myself and change myself. I’m not looking for anybody to do anything for me.”

Gates, who is on the board of trustees at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, used the event to speak about the rolling back of affirmative action—procedures put in place to promote those who belong to groups regarded as disadvantaged or subject to discrimination in their applications to public institutions—in the US. “I wouldn’t have got into Yale without affirmative action,” he said. “The Supreme Court, the American right, are going to end all of that… they have panicked and thought: too much power, too quickly, for Black people, and they’re trying to roll back the clock.”